I went today to see the Orbital, the monument by Anish Kapoor erected at the London Olympic Park. Or rather I didn’t because, as you can see above, people are not allowed in at the moment, while the majority of the site is being demolished and removed. What they suggest is going to the department store John Lewis to have a look from their windows. The whole place looked shabby and sad, leaving the Orbital as a memorial to pop-up neoliberalism.

I’ve been following the ArcelorMittal steel company that paid for the Orbital throughout a long-running strike in France, which has recently led to a recent showdown with the new Socialist government. However, almost all the UK media insisted that the Olympics were a grand triumph of Britishness and any such discussions were considered all but treason.

Get out to Stratford now and it’s not very uplifting. You can only dimly see the park through screens as you leave the station. You then have to walk through a branded shopping mall of the Prada/Hugo Boss variety. I went into one shop to get a pencil and, as I was just about the only person there, I got into a talk with the shop assistants. It turned out that these upscale segments were “pop-ups” and would be kept open only until Christmas Eve, when they would be taken down and all the staff would lose their jobs. Lovely timing, that. A nasty young manager, who obviously had a degree in marketing, came over to silence this unprofitable conversation between human beings. I went out to the back of the fancy shops and, sure enough, they were just jacked up boxes.

The structure itself will disappear, as the Olympic site across the road already is doing, having ceased to be able to make a profit.

Denied access to the park, I walked in the cold to try and get to see the Orbital. The architects had clearly thought about how to monetize even a sight of the place because the sidewalks were parapeted with little Berlin walls to prevent you from catching an unauthorized glimpse at 500 metres.

As you can see, a bit further down, the top of the wall was now lowered so you could see Mr Kapoor’s masterpiece. It’s a odd duck and no mistake.

Formally, it’s a mess with the extension from bottom left off into space on the right distracting and breaking the flow of the piece. It looks better from the other side, as I saw later from the train, but I couldn’t photograph through the glass. Even so, what is this? There’s a viewing platform on top of what looks like one of those terrifying circular exits to European car parks. The spectacle is, simply, the spectacle. Or was.

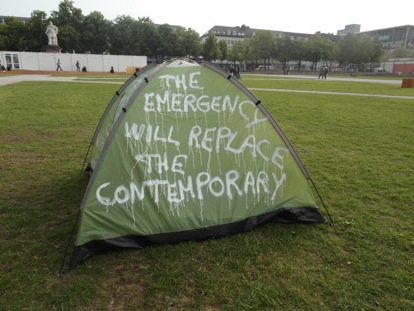

Except now that the tents have literally been folded, the view is of Stratford, an as-yet ungentrified part of the East End. Were you to get up to the top, you would see views like this if you looked east:

Of course, you’re not supposed to look this way. You were to look at the Olympic Stadium next door, smaller than I expected, or best of all towards the skyline of the City of London, home of all the most egregious scams of neoliberalism from CDOs to LIBOR and who knows what else.

Kapoor claimed an affinity with Taitlin’s legendary Monument to the Third International. Hogwash. What it actually looks like is a folded-in combination of the characters for pounds, dollars and euros: £/ $/ €. So I suppose that in a way, it really was the most appropriate monument that there could have been.