If you live in these peculiar United States, you might almost believe that the most important thing in the world is how many times Mitt Romney lied in the debates (trick question: he always lies). Unreported and undiscussed, a wave of strikes is spreading across the regions of the world that were most affected by the global social movement. The shift from Occupy to Strike is underway.

Tunisia

This is where it all kicked off. Today, the entire journalistic profession went on general strike to pressure the government to accept laws passed in the first weeks of the Arab Spring guaranteeing freedom of the press, following months of demands. And won. While these laws have perhaps to-be-regretted state of exception clauses, they are detailed and extensive, covering all areas of intellectual, journalistic and artistic expression. Light years ahead of where the American-backed dictatorship of Ben Ali had been, these laws are comparable to any liberal democratic state.

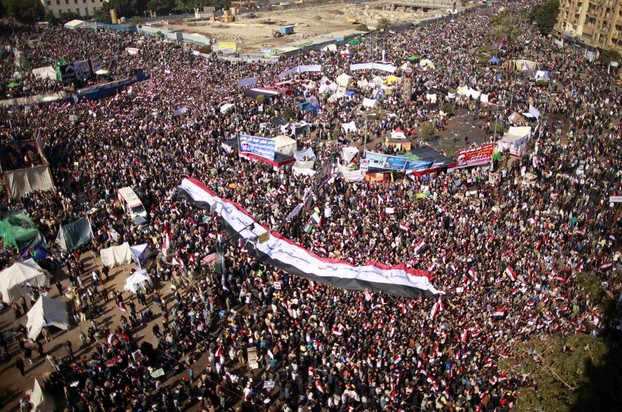

Egypt

Just as with the Arab Spring, the strike wave has extended to Egypt. In the forefront here are doctors and other medical personnel. After a series of assemblies last May, doctors called for one day strikes on May 10 and 17. Their demands are simple: effective pay scales for all medical staff, an increase of the health share of the national budge to 15% from its current 4.5%, pay increases and free public health care. Watch this excellent video from Mosireen that explains the new strike that began on October 1 and is set to continue until demands are met:

It discloses a shocking lack of facilities, armed attacks on hospitals, and that the salary of a 30 year veteran hospital consultant is only $200 a month. Emergency rooms are still open and people needing surgery are being treated: without charge.

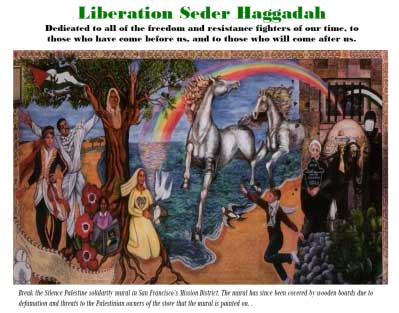

Doctors now plan a mass resignation of 15,000 physicians to compel action–like some Occupy actions, they are waiting until that many have committed before launching the resignation tactic. The ethical nature of the strike is noticeable: just as Tunisia called for the right to free expression, Egypt advances the concept of health care as a human right.

Spain

This wave of rights-based activism has spread to Spain. Unremarked in all the discussion about austerity and the euro in the business pages has been a series of drastic education cuts amounting to €6.5 billion. School students are fed up and are planning a general strike this Thursday, like their peers in Chile, who have been striking for the right to an education for the past two years.

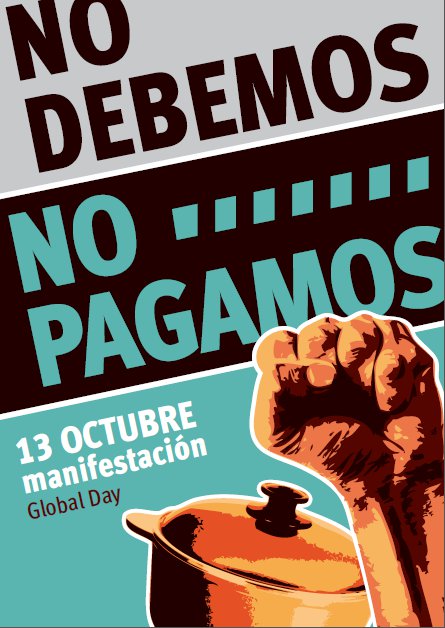

European General Strike

Today comes news of a co-ordinated general strike against austerity of all workers that has spread first across the Iberian Peninsula and now around Europe. Spanish unions today joined the Portuguese call for a general strike on November 14. Later, unions in Greece, Italy, Belgium, Malta and Cyprus have joined them. Let’s hope the connections are made and anti-austerity is presented as a political claim for fundamental democratic and human rights.

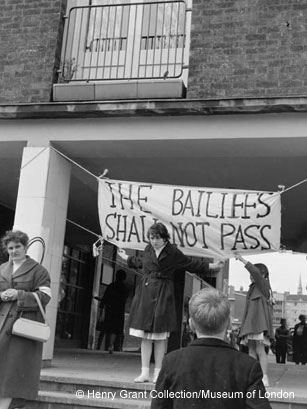

United Kingdom

A weekend march planned by the Trades Union Congress against the austerity measures and cuts in the UK has morphed into a call for a general strike. Legal prohibitions on striking put in by Thatcher and Blair have limited options for the unions but The Guardian reports:

A leading industrial relations barrister, John Hendy QC, argues that a general strike against government policies …can take place under the European Convention of Human Rights…. Steve Turner, Unite’s director of executive policy, said: “This will be a political strike. There will not be any ballots and it is our view that political strikes are not unlawful.”

No doubt the Tory government will take a different view…but a major union calling for an explicitly political strike is, well, striking.

Estados Unidos

And will the wave carry here? N14 would be after the elections and if, god forbid, there’s a President-elect Romney, it would be a great time to make a statement. It’s not at all likely. There is some agitation building up in New York about yet another rise in public transport costs that could see some actions. It’s not likely to be the labor movement that answers the European call, not least because there’s really no precedent. There are those that have been more responsive…