Lately everyone has been telling me how tired I look. In part, that’s the cold that everyone in New York seems to have. Partly, it’s a way of saying that I am middle-aged. It’s also that Strike Debt is in full gear and it has been throughout so everyone is, in fact, wiped out. But it continues to be interesting and provocative so we keep doing it.

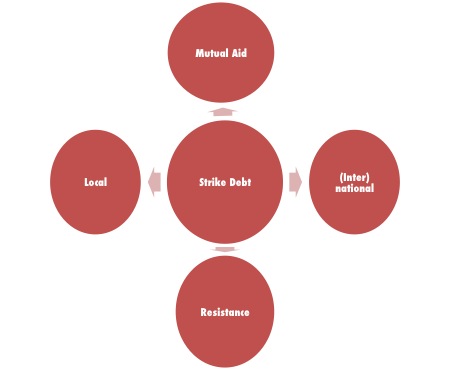

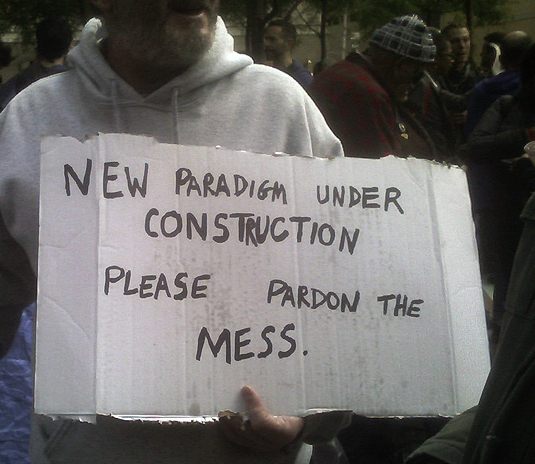

Over the course of two long discussions yesterday and today, one within Strike Debt and the other at Occupy University, the figure of Strike Debt as a set of intersections arose. It’s not “just” about the debt in other words. It’s about using debt to open new conversations and new approaches that make it possible to organize and conceptualize differently.

So the figure of Strike Debt above is both a map of how debt and debt resistance plays out, and a configuration of how the group might be organized. There are four poles: mutual aid and resistance form one axis, while the local and the (inter)national forms the other. Each site and each axis is in itself a place of intersection and none exists independently. Debt itself, after all, is a set of agreed or compelled relationships. It allows us to explore questions of human interaction, as well as the interface of the human and non-human.

Sets of related terms arise as a result of the interplay across the axes.

Cluster one: Modes of Engagement

Mutual Aid/Jubilee/Gross Domestic Product/Growth/Abolition/The Commons/ Bankruptcy/Refusal/Resistance.

These are different ways of configuring relationships to debt, credit, interest–in short, mediated human interaction in terms of value. They are not linear but reconfigure according to which term in the cluster you stress (like mind-mapping software if you get the geeky reference). So if you stress bankruptcy, it might be as refusal or resistance but it might also have to do with GDP. It might be a way of talking about Jubilee. Growth becomes a question rather than a solution. It might not be growth in conventional terms but growth of leisure time or social services.

Cluster two: Politics of Affect

Calm/Love/Radicalism/Encouraged/Healing/Smile/Feminism/Trust

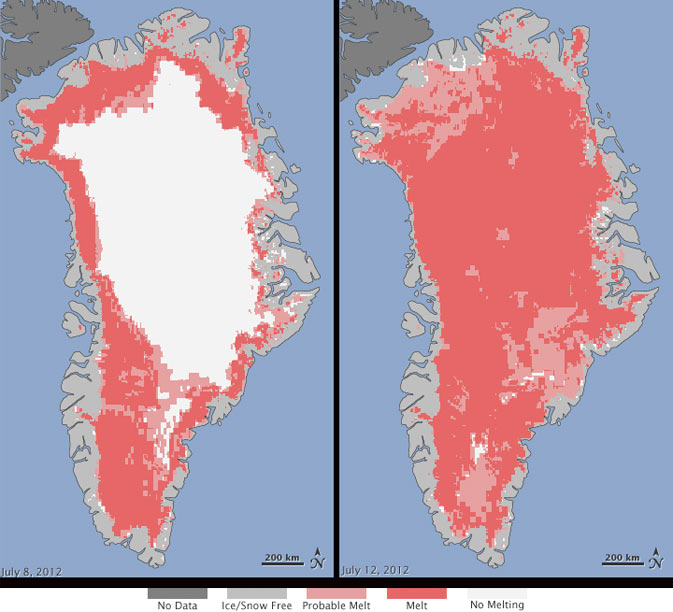

These are all terms used by participants at the end of the OccU session on Debt and Climate this evening. They are not words often associated with either debt or climate change. The ways in which people worked together to see intersections and commonalities, as well as emerging tactics to engage with these issues, generated this positive sense. Just as it has been crucial to make people feel better about being in debt by talking about it, so does climate change need to seem scaleable. Presenting debt abolition and climate change mitigation as mutually reinforcing solutions–because debt cancellation reduces the need for growth and allows for lower emissions–was more successful than dealing with the two issues separately.

Cluster three: Tactics

Mapping/Aesthetics/Organizing/Social Cost Accounting/

Stop Shopping/Countervisualizing

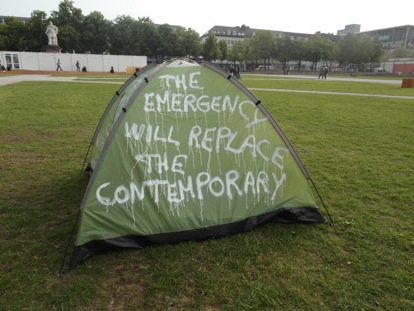

Some of these terms might be interchanged with Modes of Engagement and vice-versa: they are intersecting. Mapping, though, emerged repeatedly as a key tactic for debt resistance and climate change mitigation. In short, it’s a fundamental mode of countervisuality. Aesthetics, both in the formal sense relating to artworks, and the generalized sense of bodily perception was also something we wanted to reclaim from the banner to the performance and the street action.

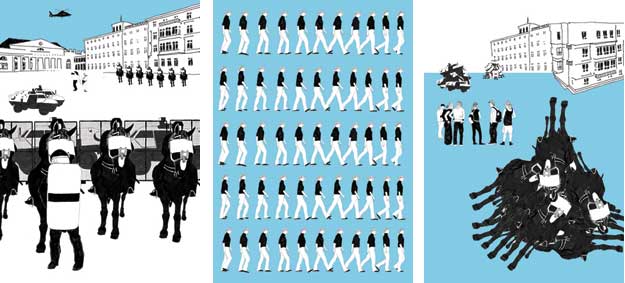

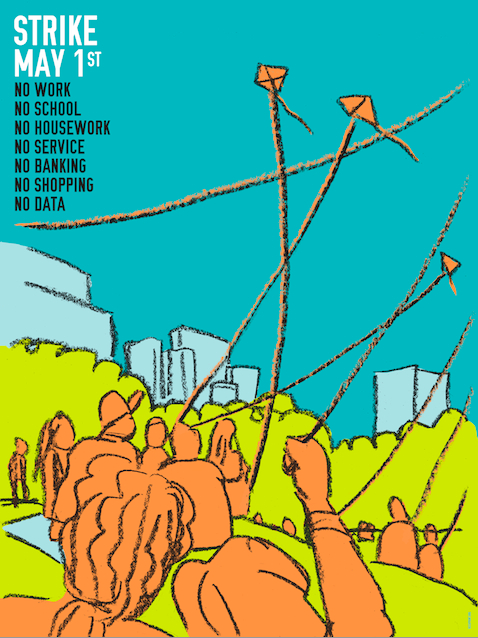

Want to see what this intersection looks like? Check this video promoting the 14N International Strike in Europe: