I’m writing this post, like all the others, on a Mac computer that proudly advertises it is made from solid aluminum (or aluminium). That aluminum was probably mined from land belonging to indigenous people. Today workers for Spectra Energy began constructing a pipeline that will bring fracked natural gas and its accompanying radioactive Radon right into the West Village, close to where I live. Needless to say the swathes of land being destroyed by this extraction once belonged to the indigenous people here too. The once-heralded immaterial knowledge economy feels a lot less real than this recolonization of everyday life. Wherever you live, it’s right there in increasingly similar ways.

In the swirling moments around 1968, the Situationists declared that there was an ongoing “colonization of everyday life.” Perhaps it’s an indication of what McKenzie Wark has called the “disintegrating spectacle” that this drama can now be visualized. It’s a surprisingly material process, the physical extraction of energy and minerals displacing first the indigenous, and then whomever else happens to be in the way. We are reminded once again that, as Walter Mignolo has put it,

coloniality is modernity.

The endless process of accumulation is revisiting both places and materials that it has already used in a different way to produce this recolonization.

So what’s in my Mac? Making aluminum an incredibly destructive process. Three tonnes of bauxite is required to produce 1 tonne of alumina. It’s nearly all strip-mined because bauxite tends to close to the surface. Only half a tonne of aluminium can be extracted from 1 tonne of alumina. So it’s a six to one waste to product ratio. Mining regions are devastated.

The supply chain for a globalized material like aluminum is not transparent. The nations offering the largest supply include Australia, China, India and Brazil. You’ll be aware of the explosions in Apple’s China plants caused by aluminum dust.

In Australia, 60% of all mines are either situated on land still recognized as Indigenous or adjacent to it. On the Burrup Peninsula, home to the extraordinary petrogylphs of the Yaburara people, some 90 of the 118 square kilometres has been zoned for industrial development.

The pattern in India is similar. India’s Center for Science and the Environment reports:

If India’s forests, mineral-bearing areas, regions of tribal habitation and watersheds are all mapped together, a startling fact emerges – the country’s major mineral reserves lie under its richest forests and in the watersheds of its key rivers. These lands are also the homes of India’s poorest people, its tribals.

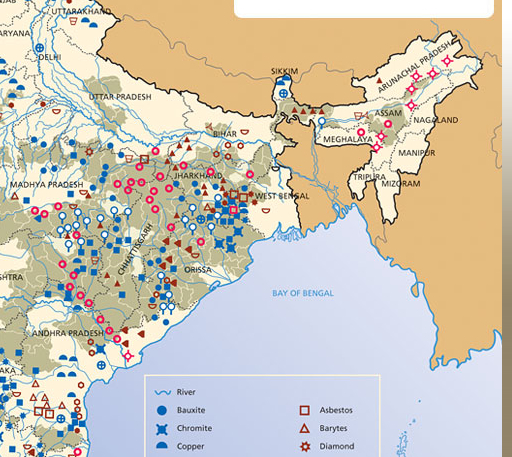

The map below indicates mines with symbols and areas of poverty/Adavasi habitation with dark shading:

The reasons are clear. According to an Amnesty International report of August 2012:

Vedanta’s human rights record falls far short of international standards for businesses. It refuses to consult properly with communities affected by its operations and ignores the rights of Indigenous peoples.

We could generalize that statement to say that the recolonization of everyday life flatly ignores what it considers to be unnecessary restraints on profit generation like rights or existing law.

In Canada, according to a devastating piece by Andrew Nikiforuk, the neoliberal Harper administration has literally rewritten the law to enable the creation of a tar sands pipeline into and across the Great Bear Rainforest. The forest has hitherto been a model of sustainable development, combining:

ecotourism, renewable energy, sustainable forest products, shellfish aquaculture, and the restoration of First Nations’ access to fisheries.

In March 2012 the administration bundled together an extraordinary assemblage of deregulation into one package and passed it as an omnibus bill, undoing not only the rainforest protections but almost all aspects of environmental monitoring that might hinder the operations of Big Oil.

The distinguished marine ecologist Ragnar Elmgren of Stockholm University called it “an act of wanton destruction…the kind of act one expects from the Taliban in Afghanistan, not from the government of a civilized and educated nation.”

Leaving aside the cultural hierarchy implied in this statement, which is a tad unfortunate to say the least, what’s notable is that this recolonization–or perhaps more exactly, reversion to colonizing conditions–has no exception for the EuroAmerican “white” person.

The Fourth World can be permitted a wry smile. The West Village, home to Sarah Jessica-Parker and other glitterati, is now not only subject to the mad NYU expansion, which will put construction in the area for twenty years and leave it looking like downtown Omaha, but now it’s getting a fracking pipeline. So as much as the global city likes to present itself as an oasis from the actual conditions created by financial globalization, they have now returned to sender.

As I mentioned, it’s happened before. Nikiforuk calls the tar sands product by its traditional name: bitumen, also known as asphalt. It’s that filthy dark black stuff they use to coat roads. And in the beginnings of the industrial period, they used it as part of the immaterial labor of the day. For artists always searching for a true black, bitumen appeared to be a great discovery. So in museums all over the world you can see early nineteenth century paintings that are gloomily dark and cracked. Bitumen never fully dries, so it expands when warm and contracts when it cools, creating the cracks and allowing it to spread across a canvas. The great canvases of Romanticism in particular are literally smeared in oil.

The most famous example is The Raft of the Medusa by Géricault.

The coal-smoke yellow and impenetrable gloom of the canvas are the gifts of fossil fuel painting. Ironically, the subject concerns a shipwreck of a colonial voyage to Africa that led the survivors to cannibalism. Once again, the recolonization of everyday life has us cannibalizing ourselves, dying for fuel in a tragic farce.