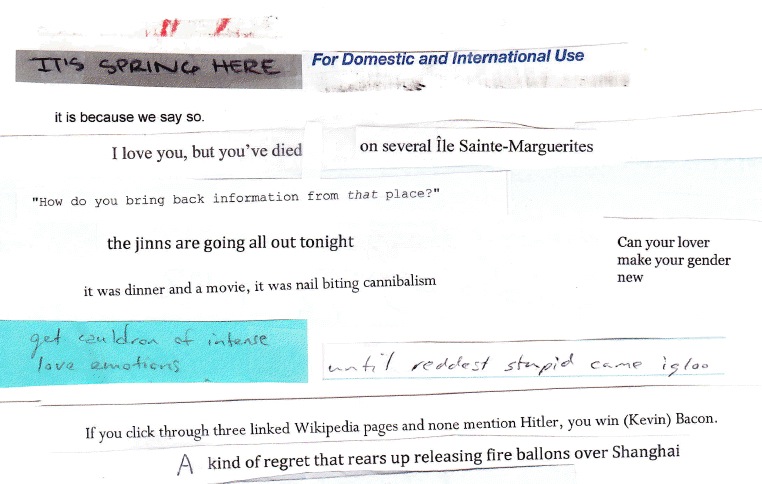

As predicted, Greece is having its Antigone revolution in refusing to abide by the Law in favor of kinship. For the majority who voted for Syriza and other anti-memorandum parties, mutual aid outweighs obligations to creditors. In the first days of this project, you may recall, I was very taken with a reworking of the Antigone legend in the context of the global social movements by Italian performance group Motus. The proper treatment of the dead body was later visualized by the Egyptian video collective Mosireen. And so when the chant “A-Anti-Anticapitalista” became the subject of a later post, I rewrote it in my head in my geeky way to go “A-Anti-Antigone.” Amazon knows that I am interested in Antigone now and when Ann Carson’s new book Antigonick was published this week, they told me. And this was uncanny because I am known as Nick to my friends.

Actually, what the book, a reworked translation of Antigone, is called is open to question. The cover says:

ANTIGO NICK

But the inside front page and Library of Congress listing have Antigonick. You won’t notice that at first because you will be admiring the beauty of the book.

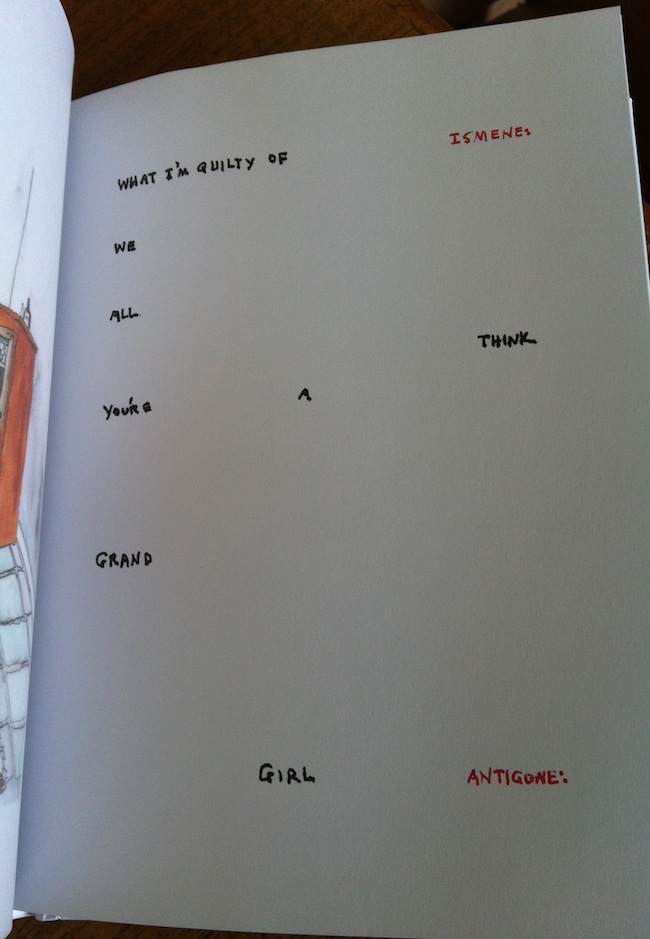

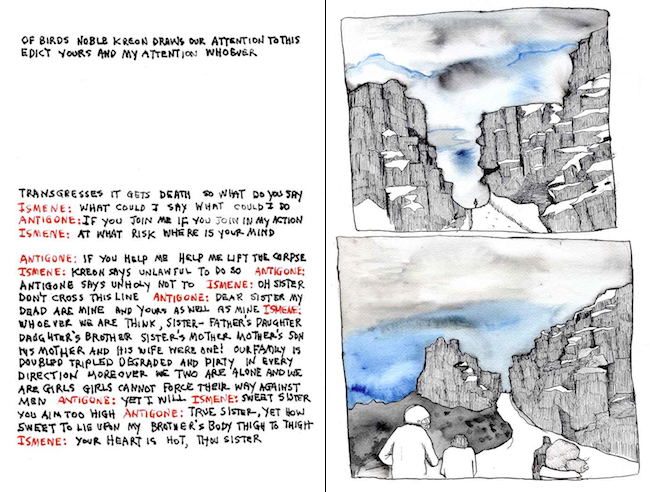

The text was hand-inked on the page, in black and red ink [so red in quotes does not now indicate a hyperlink] then photographed–it’s a bit smudgy sometimes but very striking.

The text was hand-inked on the page, in black and red ink [so red in quotes does not now indicate a hyperlink] then photographed–it’s a bit smudgy sometimes but very striking.

Bianca Scott has produced overlay color drawings that intersperse the text on translucent paper. The only book I can remember seeing like this recently was by the artist Cai Guo Qiang and indeed this one was printed in China (no further details are given). Without being unkind, there’s a story about labor, costs and outsourcing there that might interest Antigonick.

Bianca Scott has produced overlay color drawings that intersperse the text on translucent paper. The only book I can remember seeing like this recently was by the artist Cai Guo Qiang and indeed this one was printed in China (no further details are given). Without being unkind, there’s a story about labor, costs and outsourcing there that might interest Antigonick.

Then you notice that this is not at all a literal translation. It begins wonderfully (Carson’s caps):

[ENTER ANTIGONE AND ISMENE] ANTIGONE: WE

BEGIN IN THE DARK AND BIRTH IS THE DEATH OF

US. ISMENE: WHO SAID THAT ANTIGONE: HEGEL

ISMENE:SOUNDS MORE LIKE BECKETT ANTIGONE: HE

WAS PARAPHRASING HEGEL ISMENE: I DON’T THINK

SO

Carson reminds us that a legend is always a question of how you tell it. And that this is a play, a text to be performed. In the list of characters we find:

Nick a mute part [always onstage, he measures things.]

We’ll come back to him in a minute. The references to Beckett and Hegel tell us that we can’t hear Antigone as if we were ancient Greeks. This is a modern drama now. Isn’t it just.

KREON TO ANTIGONE :YOU KNEW IT WAS AGAINST

THE LAW ANTIGONE:

WELL IF YOU CALL THAT LAW

By the unspoken convention (Nick’s measures), words in red have so far indicated the names of characters. It’s not too much to say that the LAW is a character in Antigone. Or it could also be “just” an emphasis. Or it could be an emphasis on the just, over the law.

Such undecidability is of course contrary to Hegel, who held that

in a drama [spiritual powers] enter in their simple and fundamental character and they oppose one another.

It might be thought that the drama of Oedipus was a (literally) classic example. But it depends. In a review in the New York Review of Books (paywall), Peter Green points out that it was held that Oedipus’s father Laius was attracted to:

Pelops’ son Chrysippus, and carried him off in the first (but by no means the last) homosexual abduction known to Greek myth. Pelops cursed Laius; and the latter’s death at the hands of his son, who then unwittingly married his mother Jocasta, was the working out of this curse.

In this version, the Oedipus complex is more complicated and less decidable than it’s usually allowed to be. Again, as Judith Butler has emphasized, when Antigone talks of her brother, she could be describing Oedipus because they share the same mother. The Oedipus complex was always already queer.

And that LAW thing isn’t just the law of the father. Today Alex Tsiras of Syriza said of Greece “we are going directly to hell,” meaning a living death underground. Which is what happened to Antigone. As Carson reminds us, the myth has power today because it still affects us. She uses words like ANARCHY where the standard translation uses “unruly.” She talks of the “state of exception.” How to measure that?

In the nick. In the nick of time. By Nick.

Eurydike, Creon’s wife, mother of Haimon who Antigone was to marry, has famously few lines in Sophocles. One speech, five lines.

Carson has her speak much longer, with a riff on Virginia Woolf. Then she asks a question about Antigone [the spacing isn’t right in the quote, the lines are alternately indented but WordPress won’t allow that measure, sorry]:

BUT HOW CAN SHE DENY

THE

RULE

TO

WHICH

SHE

IS

AN

EXCEPTION IS SHE

AUTOIMMUNE. NO SHE IS NOT. HAVE YOU HEARD

THE EXPRESSION THE NICK OF TIME WHAT IS A

NICK

What indeed? The OED gives us an astonishingly long entry. It refers to a notch, a cut, a groove, whether in a machine, a tool, wood or an animal. It can refer to the vagina, as in various Jacobean dramas cited by OED. Then it is also the precise moment, later the nick of time. It is essential, what is aimed at. You can also go to the nick, a jail or prison, and be beset by Old Nick, the devil.

At the end of the play, NICK still on stage MEASURING. Measuring the collapse of autoimmunity, the collapse of debt’s capital, the capitals of debt.

Like in Beckett, who crops up here, Imagination Dead Imagine:

No trace anywhere of life, you say, pah, no difficulty there, imagination not dead yet, yes, dead, good, imagination dead imagine. Islands, waters, azure, verdure, one glimpse and vanished, endlessly, omit. Till all white in the whiteness the rotunda. No way in, go in, measure. Diameter three feet, three feet from ground to summit of the vault.

Measuring, counting the debt in the living tomb that is the Troika’s Greece, there we find A-Anti-Antigonick. An odd creature.