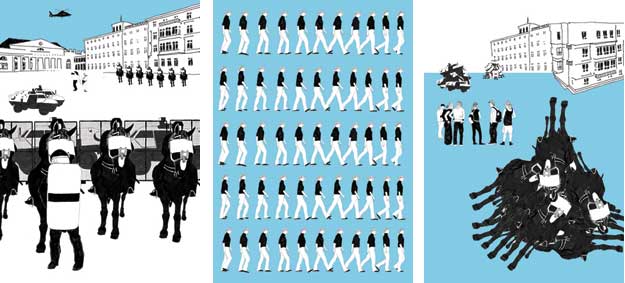

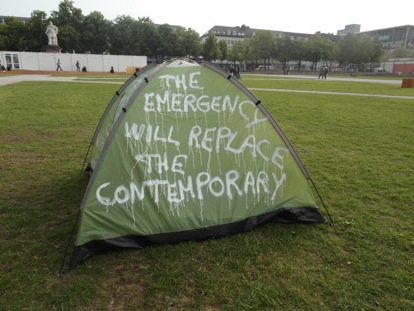

It seems that there’s a concerted effort at the level of the nation state and the transnational institution to assert that the status quo is assured. The European Central Bank has written a blank check for the Euro, pollsters are predicting a win for Obama and stock markets are back to 2008 levels. The wrinkle comes from Quebec, where forty years of organizing has laid the background for the election of the new Parti Quebecois government, committed to abolishing the tuition hike and the noxious Loi 78.

Mario Draghi, head of the ECB, announced yesterday that it would buy bonds from member nations in unlimited quantities. His action was designed to forestall all rumors that the Eurozone might break up, by restoring liquidity to nation states. For the inflation-shy German central bank this action was held to be

tantamount to financing governments by printing banknotes.

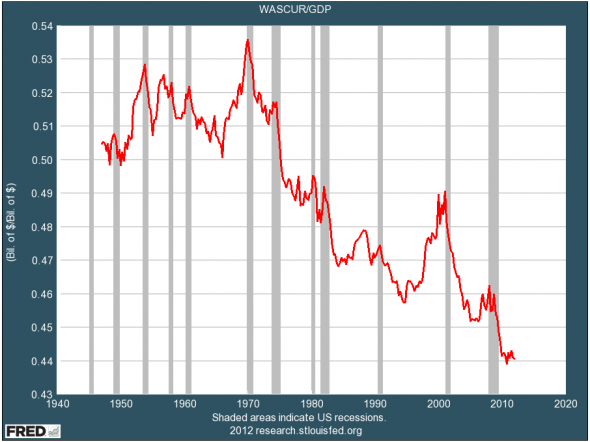

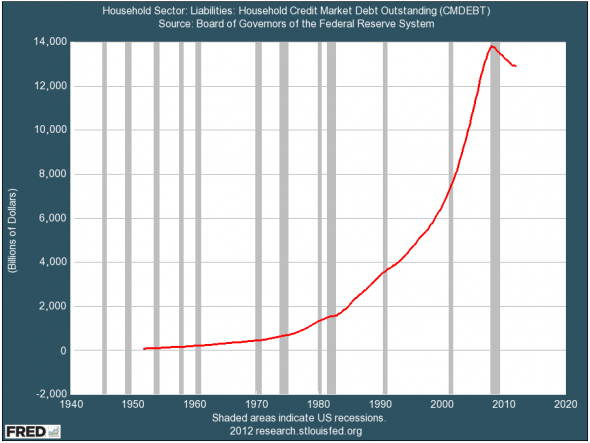

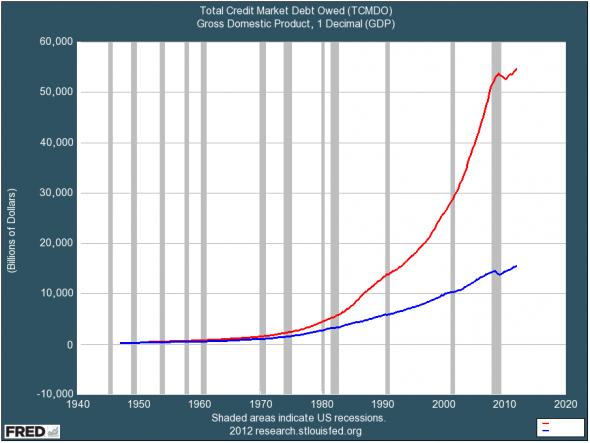

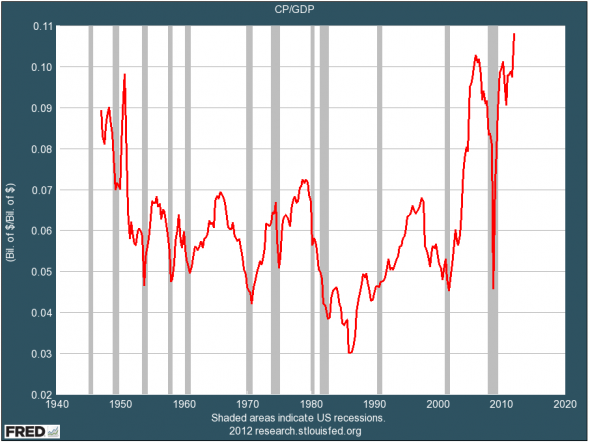

And indeed it is. Against neo-liberal economics, Draghi and other central bankers assume that there will be no inflation because consumer demand and wages alike continue to be depressed.

Across the world we see the reasons why. The US economy added no more than a rounding error of jobs last month. The battered Greek welfare state is about to undergo another $11.5 billion in cuts. Portugal increase its social security tax from 11 to 18%. Like all the other money poured by government into banks, none of this will find its way out to people.

Meanwhile, in the NAFTA-zone, Mexico is set to return to the institutional rule of the PRI and Canada remains under the oil-first government of the Liberals. The 538 blog (now hosted by the New York Times gives Obama a 77% chance of victory, which is good news in terms of preventing further neo-liberal and culture wars insanity by the Republicans. Given the low chance of the Democrats taking the House, it will nonetheless mean the continuance of gridlock, with continued impunity for banksters and no risk to the one per cent.

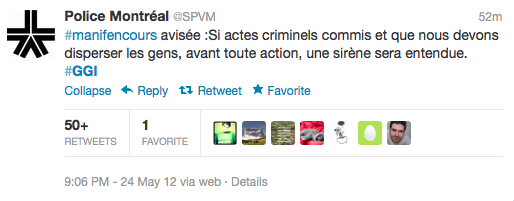

The exception to all the gloom comes from Quebec. After the narrow election win by the Parti Québécois, they smartly decided they did not want to be saddled with the Liberals’ baggage:

“We had a call from the PQ assuring us they will cancel the tuition increase and Bill 78,” said Martine Desjardins, president of the Fédération étudiante universitaire du Québec, noting students will also meet with Parti Québécois Leader Pauline Marois. “They said they will reimburse any students who have already paid.”

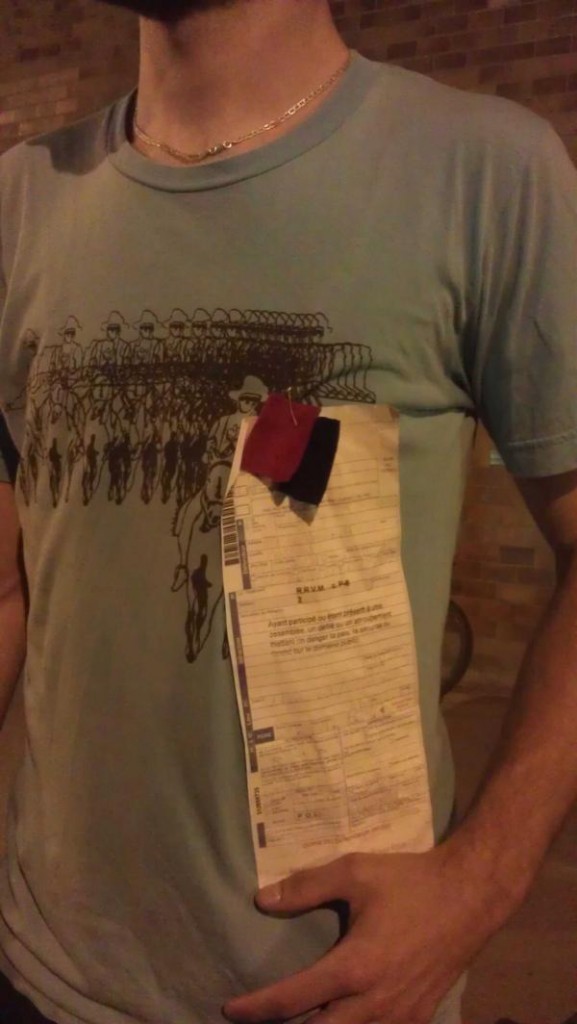

CLASSE have indicated that the national demonstration of September 22 will go ahead, in the absence of an actual repeal, and in support of their claim for a student grant increase. It will most likely have the feel of a victory party.

There are no doubt questions as to what happens next in Quebec. For now, let’s note their successul formula so far

- building a radical community over an extended period of time

- working in alliances, even with groups with whom you have distinct differences, towards specific goals

- great messaging and symbolism, together with resolute direct action

- keeping it local.

These tactics resonate with those used by the horizontal and popular movements in the Southern half of the hemisphere. They did not back down, even in the full force of law, and have made a real difference. There’s really something to see there.