Now! Visual Culture spent a day thinking about the intersection of debt, academic knowledge, old and new media in the anti-disciplinary frame of visual culture.

A very well-attended first session on debt and academic labor set the tone. Magda Szczesniak (University of Warsaw) told us that the corporatization of university practice is developing in Poland but students there are not yet in debt, while not being well-funded. She noted that the university system is still in effect “feudal,” depending on personal influence and obligation. Can the so-called deficiencies of this system be made into a virtue? For example, the failure of Polish academic publishing to generate any profit might make it easier to introduce open-source publishing.

Pamela Brown from the Occupy Student Debt Campaign outlined the terrifying statistics, generating despairing laughter. She explained the corporate structures that underpin the debt machine: 94% of elected officials have won their campaigns by being the most efficient fund-raiser, mostly coming from the financial industries. No fewer than four bills reforming bankruptcy laws have failed. The current debt forgiveness proposal in Congress is rated as having a one percent chance of success.

She recalled a debt-strike in Co-Op City in the Bronx during 1976, when 15,000 people refused payment for over a year because they felt they were supporting the debt burden of the management corporation. However, there are no indexed images of the event online, indicating a structural absence in the collective image bank and the beginnings of an explanation for the insistence that debt refusal is immoral and unprecedented. It also suggests an important research opporunity.

Ashley Dawson argued that student debt is itself a crisis of visuality. It is hard to visualize, unlike foreclosure, for example. In particular, how do we visualize the underlying moral contract? There have been attempts to represent the size of the debt, or the de facto indenture of student loans, but credit itself is hard to visualize. He recalled the history of the establishment of the open admission and free tuition policy by direct action in the 1970s at CUNY, where he teaches. President Nixon was afraid of the production of an “educational proletariat” and Republicans used the bankruptcy of the city in 1977 to end free tuition. CUNY was a harbinger for the casualization of the academic workforce, which is now half the size of its 1975 benchmark. Columbia is the third largest employer in New York but is tax exempt.

McKenzie Wark pointed out that activists often make the best researchers, citing David Graeber. He also noted that this isn’t capitalism “it’s something worse.” There is now a problem of representation in general because the mechanisms of capital are so abstract. The humanities should now be doing this kind of important work rather than sticking to the tried-and-testd because it would both make a contribution and be more likely to generate employment.

In the next session on new media publishing, Tara McPherson argued that we can’t visualize just the screen, we need to understand the machine. Databases normalize data and abstract them from that which they index. That point reflects back on the questions of economic visualization discussed earlier. For example, the graph itself was created in synchronization with the idea of the market as part of eighteenth century mercantilism. As many people observed in the debt panel, these forms don’t tend to be convincing when you’re arguing against neo-liberalism. In this context that becomes less surprising. Graphs abstract people into a positivist database. As McPherson put it, “technological systems are weighted in favor of positivism and control,” but they don’t have to be. We need to actively engage the form not just receive the content.

The insistence from the student debt campaign on naming and identifying debt as a personal and political issue rather than as an abstract data point is, then, a countervisuality to the dominance of the “market.” Talking to people about debt is in itself a form of resistance and politicization. The same point can be made in relation to digital media studies. Humanities scholars have embraced digital technology as a form of very large data analysis, a move away from affect. By contrast, Occupy Student Debt links data to narrative. Paradoxically, certain sectors of humanities new media scholarship might be as much part of the problem as part of the solution.

Deborah Levine’s extraordinary Scalar project called Demonstrating ACT UP (not yet open access) uses the affinity groups of ACT UP as an organizing strategy. By tagging individuals, the tag cloud allows you to visualize a vast database of ACT UP materials at a human and personal level. Because it relies on the affinity groups that drove the project, this organizational strategy is both horizontal and political.

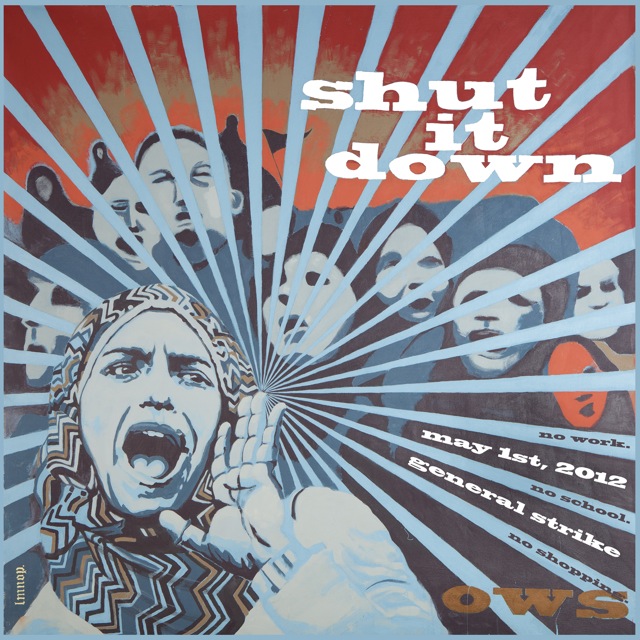

In the afternoon, members of the Brooklyn Filmmakers Collective, who made some key films for the Occupy movement in its earliest days, talked about collective film making.

This seven-minute film was edited in ten hours, moved from conception to release online in ten days–compared to the average edit of seven minutes in two weeks. It was so widely seen that it came to have a life of its own as a guide to Occupy.

BFC actively try to challenge the hierarchical structures of the industry and its mantra: FILMMAKING IS A BUSINESS, focusing instead on passion projects. “Collective” here means everything from close working together to a community of filmmakers meeting together and sharing work for collective criticism in a weekly critique workshop. Their films are very different in form, production and content.

The film Spoils deals with dumpster diving in Brooklyn, a central part of Freegan culture. Here the film was made in fairly traditional way with a director in charge.

Welcome to Pine Hill on the other hand was collectively made and produced in a non-budget context, meaning time and materials were donated. The film has won prizes all over the place, including at Sundance, so it’s no hindrance to the reception of the film. In a similar fashion, the Meerkat Media Collective work non-hierarchically, share tasks and make sure that people get experience in tasks that are new to them. They reminded me of Mosireen from Cairo, who have been working in similar ways.

Academia is still uncertain about these new ways of working. Horizontal ways of working and thinking are still emerging and still contested. As the weekend continues, it’ll be interesting to bookend conclusions tomorrow with the Occupy Theory Debt and Education Assembly in Washington Square Park on Sunday.

Like this:

Like Loading...