I’m in San Juan, Puerto Rico, for the American Studies Conference. While this is perhaps the most progressive, even radical, academic event, it’s heartening to hear how many people have heard of the Rolling Jubilee. And how many love it. At the same time, as ever, it’s useful to look back at our situation from the decolonial perspective. The realization follows that New York is just another North Atlantic island with many of the same problems as places like Puerto Rico or Martinique.

Outside the hotel, the sea comes right the way up to the building here in Condado. Trucked in sand tries to hold it back but where the main hotels are here, there’s somewhere between twenty and thirty years before it floods. Barrier islands are no longer places to live.

On a panel about Caribbean environmental politics, two familiar themes emerged. First, zones of flooding and poverty tend to coincide and diminish the social agency of those who live there. If, as urban ethnographers have argued, you can think of cities as bodies, they also have embodied memories that are revealed at times of crisis. In this sense, they occupy themselves by making visible what needs to be done.

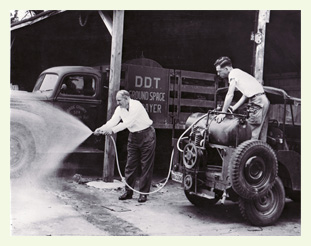

In Martinique, we learned, environmental activists have no issue with seeing the resonances between the current attempts to use carcinogenic pesticides, turn uninhabited beaches into hotels or mangrove swamps to shopping centers and the colonial past, including slavery. In fact, the presentation began with the monument at Anse Diamant to enslaved Africans drowned off the coast of the island.

The figures are white because that is the color of death in West Africa from where the enslaved probably came. They look forever at the place where the ship went down and, in traditional African belief, the departed would have traveled from there via the underwater world of the spirits to an eventual return to Africa.

On the island today, activists visualize two classes: the béké, or the descendants of the slave-owners and colonists, who control all economic activity; and the people or the Martiniquais. Here is the divide between the one per cent and the 99% in the decolonial context. By decolonial, I mean that the formal colonization is over and yet the influence of the colonizers and their allies is still dominant.

The next point was more thought provoking still. Although groups like Assaupamar, for the preservation of Martinique’s culture and ecology, use the slogan Pays-nous (our country), they also recognize that, whether of African or European descent, they are not the original inhabitants. They stress a politics of responsibility rather than ownership, which the béké class do not–perhaps cannot–recognize.

I know there are many differences but I am also struck by these similarities. Coalitions of the 99% seeking to work past historical differences against a common perception that it is not possible to have the one per cent recognize what is said. Highly racialized cities, with clear segregation that overlaps the flood zones. Remember that people of color were moved to the Far Rockaways in the first place to make way for Lincoln Center so the one per cent could go to the opera.

If we are to acknowledge the realities of climate debt, we have to provincialize New York and see that it is just another flood-prone former colonial port with a race and class problem. Wall Street was the site of a slave market and a wall to keep out the indigenous. The material practices have changed but there are clear resonances that we have to learn to hear. There has been so much discussion of the memories evoked by the boardwalks destroyed in Jersey and the Rockaways. We need to listen more closely.