So I had this idea for Memorial Day weekend that it would be interesting to look back at past protest literature from the New York area and see what could be learned, in the manner of all those op-eds about nineteenth-century presidents and Greek wars. I looked again at Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Jane Jacobs’ Death and Life of Great American Cities. For all the obvious differences, there’s one clear similarity: the NYPD were awful even then.

Carson’s very title depends on a conceit that I don’t think still works very much. It comes from the idea that because of bird death resulting from the use of the pesticide DDT, there might be a spring without bird song. Although I did have a friend go back to England because he missed the song of the thrushes (a small brown bird), I’m not sure that most of us would register the difference now. I rarely notice birds singing, except when starlings are massing for migration. As we now mostly travel in sealed vehicles, more often than not with ear-buds in place, that interface is less vital than it once was.

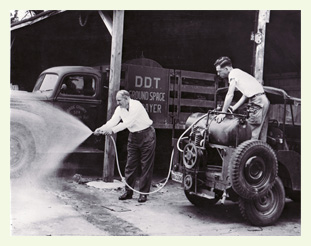

On the other hand, Carson mentions that after the village of Setauket on the north shore of Long Island was sprayed with DDT, a horse drank from a trough in the high street–and died immediately. The toxicity of DDT was its selling point and Long Island was doused with it to try and eradicate the gypsy moth to no avail. In the years since there has been a notorious breast cancer hotspot on the Island. DDT is said not to be a carcinogen and all the studies made have failed to show a link between pesticide use and cancer–except it might be said for the one in real women’s bodies in real space. Rachel Carson died of breast cancer shortly after her book was published in 1962.

But if you Google Carson and DDT, half the entries you will see accuse her of being a murderer. The bizarre conceit is that malaria in the dominated world could be more effectively eradicated with widespread use of DDT and the fact that is not is Carson’s fault. There is a perfectly effective way to prevent malaria, which is to give people treated mosquito nets. It works, it’s cheap and it has no side-effects. But giving money for that would not have the fun of “demolishing” an environmental pioneer.

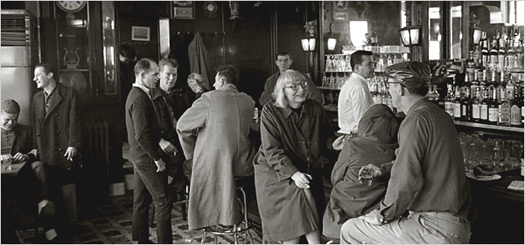

The New York City described by Jane Jacobs is perhaps even more remote than the world of horse troughs and bird song in Carson’s book. It’s a place where you can leave a key for a visiting friend at the local deli and everyone has an eye out for the kid in the street. In fact, this culture of what she directly calls “surveillance” is a bit creepy: when people encircle a man who is trying to get a child to follow him, it turns out he is her father. She talks off-handedly of a neglected park in Philadelphia becoming a “pervert park,” meaning a place for same-sex assignations in the era of the closet. There’s no street politics in this book, rather a permanent watchfulness that takes its pleasure in seeing that “all is well.”

Jacobs’ view of the mixed use, high density urban space has become canonical now, even if her follow-up thought that “slums” should be left alone has not. Much of her argument against the Le Corbusier influenced city planner now seems a bit slow-going, so thoroughly has the view reversed. On the other hand, she’s completely right when she says:

that the sight of people attracts still other people, is something that city planners and city architectural designers seem to find incomprehensible. They operate on the premise that city people seek the sight of emptiness, obvious order and quiet. Nothing could be less true. The presences of great numbers of people gathered together in cities should not only be frankly accepted as a physical fact – they should also be enjoyed as an asset and their presence celebrated.

You could apply this insight to see why Bloomberg et al. originally left Zuccotti alone to transform itself into Liberty Plaze: because it simply never occurred to them that anyone would be interested, still less want to join in or follow the Occupiers’ example.

Jacobs waged her campaigns by local petitions that she would then take to the Board of Estimate, a land-use body composed of the Mayor, the Comptroller, the Council President and the Borough Presidents. It met once a week and could be petitioned by citizens, until the Supreme Court abolished it in 1989. If this sounds like a democracy gone by, that’s certainly the case. On the other hand, look what happened to Jacobs in 1968:

Jane Jacobs, a nationally known writer on urban problems, was arraigned in Criminal Court yesterday and charged with second-degree riot, inciting to riot and criminal mischief. The police had originally charged that Mrs. Jacobs tried to disrupt a public meeting on the controversial Lower Manhattan Expressway. ‘The inference seems to be,’ Mrs. Jacobs said, ‘that anybody who criticizes a state program is going to get it in the neck.’”

— The New York Times, April 18, 1968

Now that sounds familiar enough: being charged with rioting for trying to express an opinion at a public meeting. So it turns out that some things never change.