How can we develop David Graeber’s insights into the importance of the imagination as a tool of resistance? Regular readers with good memories may recall a discussion about the Charter of the Forest (1217) that came out of my reading of Hardt and Negri’s Declaration. What gives me some pause about this intersection is that, while the Charter did inscribe some freedoms, it does so in the context of feudalism. While that might ironically be congenial to the present-day neo-feudalism of rents and debts, it’s not a platform for the current global social movement.

On the other hand, I have long thought, in the tradition of Tony Benn and Christopher Hill, that the Diggers do have something to offer here. So on a quiet day, I thought I might develop the thought for what it’s worth. It turns out to pose some interesting questions about the tension between the direct and the representation.

During the English Revolution (1642-49), a range of radical sects saw the end of Charles I’s monarchy as the beginning of new era and the end of slavery. Their goals were exemplified by the Diggers, inspired and led by Gerrard Winstanley (1609-76), a sometime Baptist and itinerant preacher. Winstanley was working as a cow-hand when he felt himself called upon:

As I was in a trance not long since, divers matters were present to my sight, which must not here be related. Likewise I heard these words, Worke together. Eat bread together; declare all this abroad.

If Winstanley understood this as inspiration, it is also what we would now call imagination, a vision of collectivity at a time of social, economic and political crisis, following the execution of the king. He was inspired to send a letter to General Fairfax, the army commander, asking

Whether all Lawes that are not grounded upon equity and reason, not giving a universal freedom to all, but respecting persons, ought not to be cut off with the King’s head? We affirm they ought.

This remarkable radicality was typical of his style, which insisted on following through first principles, all of which can be derived from the first sentence of his first pamphlet, written as his small group were beginning to reclaim the common and waste land on St George’s Hill, Surrey:

In the beginning of time, the great creator Reason made the earth to be a common treasury for all.

It’s worth looking closely at this sentence. Divinity was expressed as rationality, present in each individual, not as an external deity, as the forces of “vision, voice and revelation,” a trinity of the imagination. “Earth,” or land, is assumed to be the common property of all, the treasury of a land without a state. Notably, Winstanley wrote “common” not “the commons.” Having experienced the Absolutist monarchy of Charles I, he would have been very aware of the hierarchical ordering of feudalism and the setting aside of certain spaces as “the commons” did not satisfy his understanding of all land as common.

His vision was a relay of divine inspiration, internal rights, and righteousness to be grounded in a common sense of equality. Although the Diggers claimed to be restoring justice to its condition before the Fall of Man, their actions were practical and modern. By cultivating land on an equal basis and denying the possibility of exclusive ownership of the land, Winstanley envisaged sustainable small-scale cultivation as the basis of social life. His non-violent form of resistance was to advocate that workers refuse to labor for others, a refusal of the wage system at its beginnings. Historian Christopher Hill called this action the first general strike. Indeed, in a manner familiar to present-day social movements, Winstanley declared: “Action is the life of all, and if thou dost not act, thou dost nothing.”

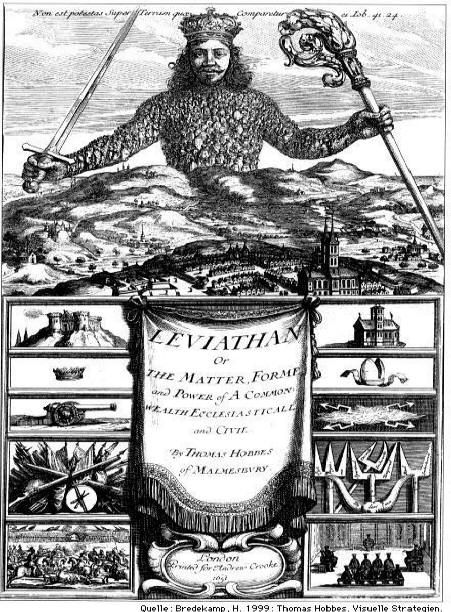

It was in response to such theories of radical direct democracy that Thomas Hobbes defined the state as Leviathan (1651). The Leviathan was the figure of the commonwealth, the social contract by which individuals arrogate their right of governance to the sovereign. Of the three possible modes of commonwealth—monarchy, aristocracy and democracy—Hobbes was convinced that monarchy was by far the most effective.

So the figure seen in the famous frontispiece to his book represents the monarchy as a living form of the social contract. The body of the King is composed of hundreds of other bodies, his subjects, combined to make the whole known as Leviathan. Hobbes imagined the Leviathan as a demi-god, like Hercules and other creatures of legend. He was interested in such “compound creatures” as he called them, as a special instance of the power of imagination, or Fancy. This was not simply an artistic or creative attribute:

whatsoever distinguisheth the civility of Europe, from the Barbarity of the American savages, is the workmanship of Fancy.

Representational images are created by this “fancy” meaning:

any representation of one thing by another.

So for all the fact that his Leviathan was filled with little people, Hobbes was civilized because he adhered to the principles of representation, whereas the “savage” believes in the direct, whether in democracy or image making. So Hobbes places a challenge: all representation is colonial.

So we might want to look into “direct” forms of acting and making, as we have of course been doing, “Direct” imaging might include photography, video, performance and other media where there has been a question about whether it is “mechanical,” or “simply” imitative or other phrases that tend in the direction of the colonial critique like “slavish” (as in imitation) or “apeing” as in copying but also as in simians.

Does this mean we must jettison all media that represent? Certainly not–but we do have to think about how to decolonize them, to disadhere them from the elite privilege they have long held, and, yes, I am thinking about painting here.

For the state colonized the land but also the faculty of imagination itself as representation. It designated sovereignty and colonial authority in and as the power to represent. Representation was a matter of sign formation, for Hobbes distinguished the mark, which is recognizable only to its maker, and the sign, which is legible to others. The opposite of authority was not, then, the primitive pre-social contract condition of the fictional “war of all against all” but the opposite of representation, which is to say, direct democracy. These ideas became equated with madness, which Michel Foucault called the “colonizing reason” of the West. By 1660 the British monarchy was restored and the first law code for the enslaved was published in the British colony of Barbados in 1661. Winstanley had called the revolution, the “world turned upside down.” Plantation monarchy restored it. Nonetheless, the common had preceded it.

I’m impressed, I must say. Really rarely do I encounter a weblog that’s both educative and entertaining, and let me inform you, you’ve got hit the nail on the head. Your thought is outstanding; the difficulty is one thing that not enough individuals are talking intelligently about. I am very completely happy that I stumbled throughout this in my seek for one thing relating to this.

The most educated, organized and active segment of humankind today, of course, are the world’s indigenous peoples. Fourth World nations — including many indigenous political entities in Europe — are in fact leading the fight against neoliberalism, as they did against colonialism. In his book The Distorted Past, Josep Fontana examines our habitual opinions about Europe’s social and political history through the lens of the evolution of modern state relations with the indigenous bedrock nations.

In his alternative view of Europe’s history, Fontana helps to explain the persistence of collective, kinship-oriented sociopolitical institutions and indigenous cultures that continue to challenge state notions of legitimacy.

http://www.amazon.com/The-Distorted-Past-Re-interpretation-Europe/dp/0631176225%3FSubscriptionId%3DAKIAJDVXOQEZ2C3DWMLQ%26tag%3Dcwisorg-20%26linkCode%3Dxm2%26camp%3D2025%26creative%3D165953%26creativeASIN%3D0631176225