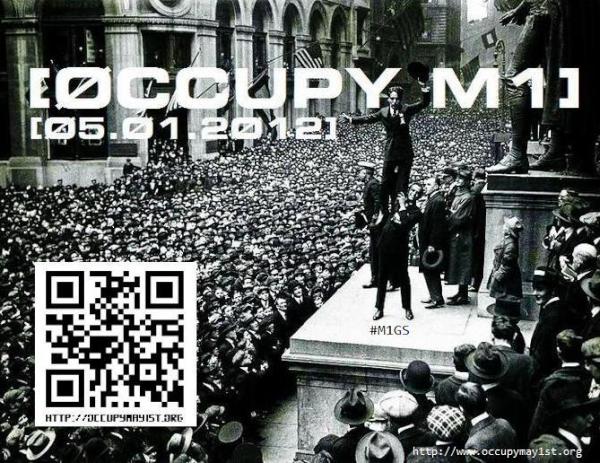

How does the Occupy movement now do its work? When the encampments began in 2011, the General Assembly was clearly the central decision making body. With the dispersal forced by the evictions and Northern winter (even its climate-changed moderate form), the affinity group has emerged as the main unit. The question now coming into the open is: occupy or affinity?

In New York, the experience of the General Assembly (GA) last year was for many of us the moment that led to greater involvement with the movement. It was, as many have testified, a really affirming experience and, at its best (as on March 17) it still can be. Too often the GA was bogged down with details of financial expenditures or unable to proceed because of the actions of disruptive individuals. Perhaps this was inevitable because Manhattan, especially downtown, did not lend itself to the creative possibilities of the Neighborhood Assemblies that have flourished in Spain, elsewhere in the US and indeed even elsewhere in New York City. Some Occupy locations, like Toronto, have recently restarted the GA, hoping to recapture the energy of direct democracy.

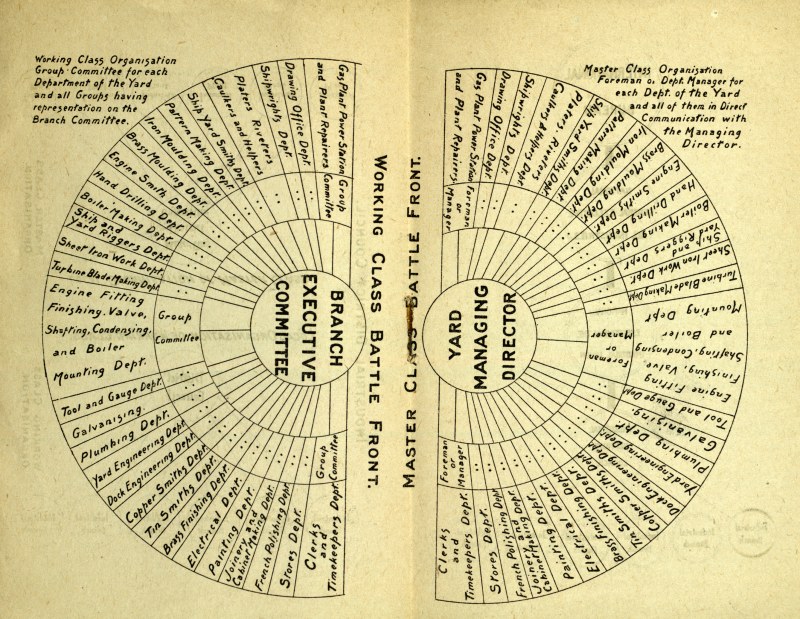

An affinity group is a set of people who decide to do something together, in this case, for the Occupy movement. Decentralized and autonomous, as the movement always claimed to be, the affinity group (AG) is something of a “back to the future” project. That is to say, while the AG is very flexible and responsive, it can also be invisible. In fact, that’s part of the point: with many being concerned about police infiltration, the AG allows for civil disobedience or other disruptive actions to be planned and carried out.

The Education and Empowerment Working Group of OWS, where I entered the movement, is now considering whether to formally disband as its affinity groups like Occupy Student Debt and the Occupy University are flourishing, so much so that people don’t have time for the extra meetings of Education and Empowerment itself. I’m one of those people and yet I still worry about this, it seems that we would be losing something important.

The issue, then, can be more clearly stated as how the new energies of the affinity groups can be made visible as a coherent movement, rather than as a set of issues in the now familiar (and ineffective) rainbow pattern. Global days of action are one such means to maintain visibility. At the same time, affinity actions bring new risks.

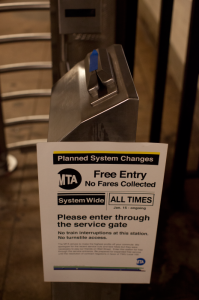

In New York, there was a recent action on the New York subway in which the gates at some stations were chained open allowing people to access the system without paying. Cleverly-faked notices were posted, appearing to authorize the free fares.

It was asserted by some that this was either an OWS action or an action in sympathy with Occupy. Almost at once local police and media began a blitz of publicity denouncing these “crimes,” including lead items on the local TV news and video from CCTV posted on the New York Times website. There was also a good deal of internal recrimination about the action, which was apparently likely to lead to disciplinary action for MTA staff. However, the CCTV showed that, whoever did this, they were not wearing MTA uniforms or working with MTA employees. In the end, then, no harm done but it’s clear that NYPD and their friends in the media are now as ready for affinity actions as for attempts to occupy.

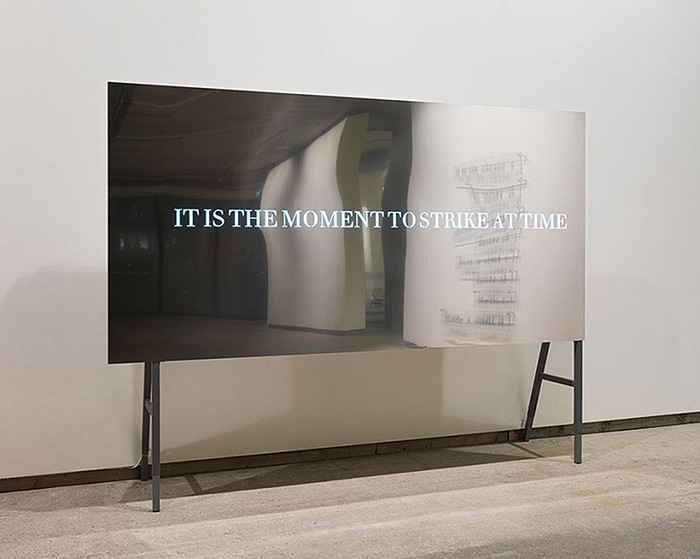

Thinking about such issues, Stephen Collis of Occupy Vancouver proposed an action recently under the slogan

“system change not climate change” and indigenous solidarity — by announcing a one-week climate occupation, with daily workshops, teach-ins, information-sessions, and actions all around the task of defending this planet from capitalist and colonial plunder.

His focus on climate was intended to be Vancouver-specific, pointing out local priorities on logging and indigenous issues. On the other hand, the Democracia Real Ya! movement in Spain is calling for a day of global action of May 12 (or 12M12), in addition to the existing calls for May Day and for the anniversary of the indignados movement on May 15.

It’s probably not a question of either Occupy/or Affinity Groups, so much as both/and. For OWS, there’s going to be a need to think past May Day, as much as we will have enjoyed ourselves. Once the arrests have been highlighted by the media and the numbers on the march have been similarly downplayed, the future may well belong to the affinity groups. Perhaps the way to maintain the visibility of the movement as a whole is precisely to keep having such periodic mass days of action.