After fifteen hours in New York City parks and streets, I’m tired in body, out of voice, but in good spirits. Occupy succeeded in visualizing itself to itself, in finding its strengths and its challenges. This is a long post because the media coverage that I have seen was so grossly unreflective of the experience I had. May Day showed Occupy has grown into a diverse, flexible and evolving movement backed by substantial numbers of people, who are not every day activists, but will turn out for events like this. And the NYPD continue to be the enemy of free expression in New York City.

So here we go. The day began at 8.30 with a picket of NYU, my own institution, in steady rain, which had been torrential an hour earlier, and soon eased off further.

NYU Picket. Credit: Max Liboiron

This “private university in the public service” has one percenters, like hedge fund titan John Paulson, on its board and is now planning a $4-6 billion expansion in the heart of Greenwich Village, which will be at least 60% (student) debt funded. This at an institution where 55% of students leave as debtors to an average of $41,000 per person, making it #6 in the nation–finally NYU makes the top ten! So a coalition of students, faculty, unions and local people have been protesting–a coalition never before achieved–and yesterday picketed the offices of the top administrators.

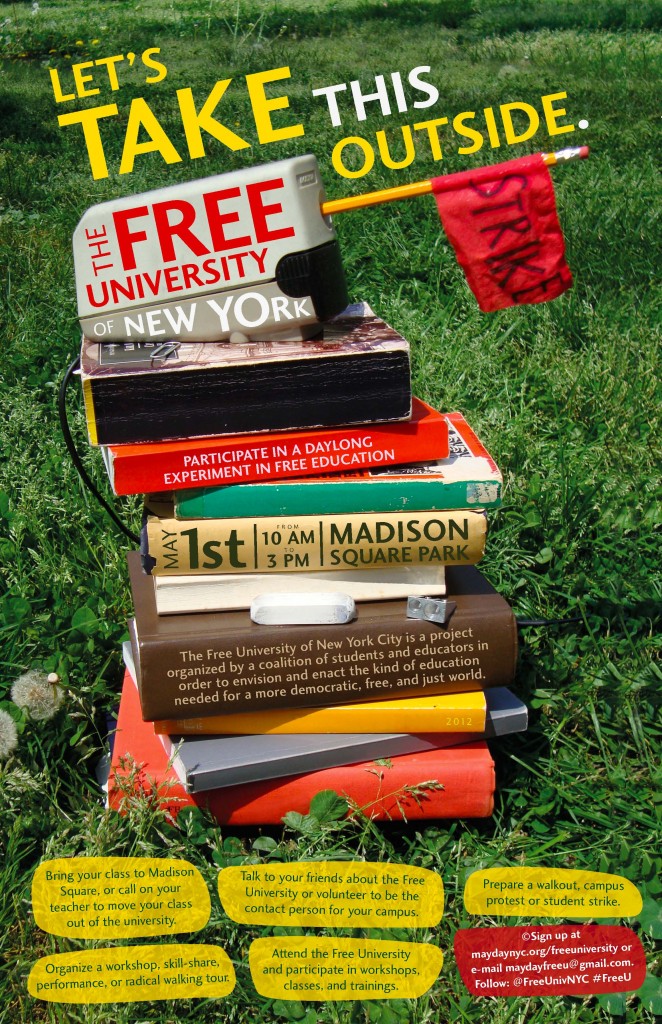

From there I head up to the Free University (my pictures unless otherwise credited), which was organized by a group consisting primarily of graduate students and some faculty, in which I had a small hand. By the time I arrived a large crowd were already listening to David Harvey speak but I could not hear much of what he had to say.

From there I head up to the Free University (my pictures unless otherwise credited), which was organized by a group consisting primarily of graduate students and some faculty, in which I had a small hand. By the time I arrived a large crowd were already listening to David Harvey speak but I could not hear much of what he had to say.

Harvey is center with the white beard

So I took part in a Horizontal Pedagogy workshop for a while, which raised interesting questions about definitions of teaching and pedagogy. These were later enacted in a workshop on solidarity organized by Marina Sitrin and others.

Solidarity workshop. Marina Sitrin center.

In the background, I saw a large group gathered to hear Andrew Ross on student debt. This was a really engaged session, with people questioning Ross for over an hour after his presentation. He commented that he was surprised to the extent to which some of the key facts are still not well known even to those who are personally implicated.

Occuprint ran a workshop on their lovely posters, which they were giving away, but I didn’t take any because I knew they would be destroyed during the course of the day. There was food provided free of charge, although I confess I did buy an espresso but I chalk that up to medicinal needs, exempt from strike prohibitions. The Free U. was an all-volunteer, co-operative space that intends to carry on working after May Day in conjunction with OccU [Occupy University] and others to reconfigure learning in the city. It was an example of mutual aid at its best, a lovely experience.

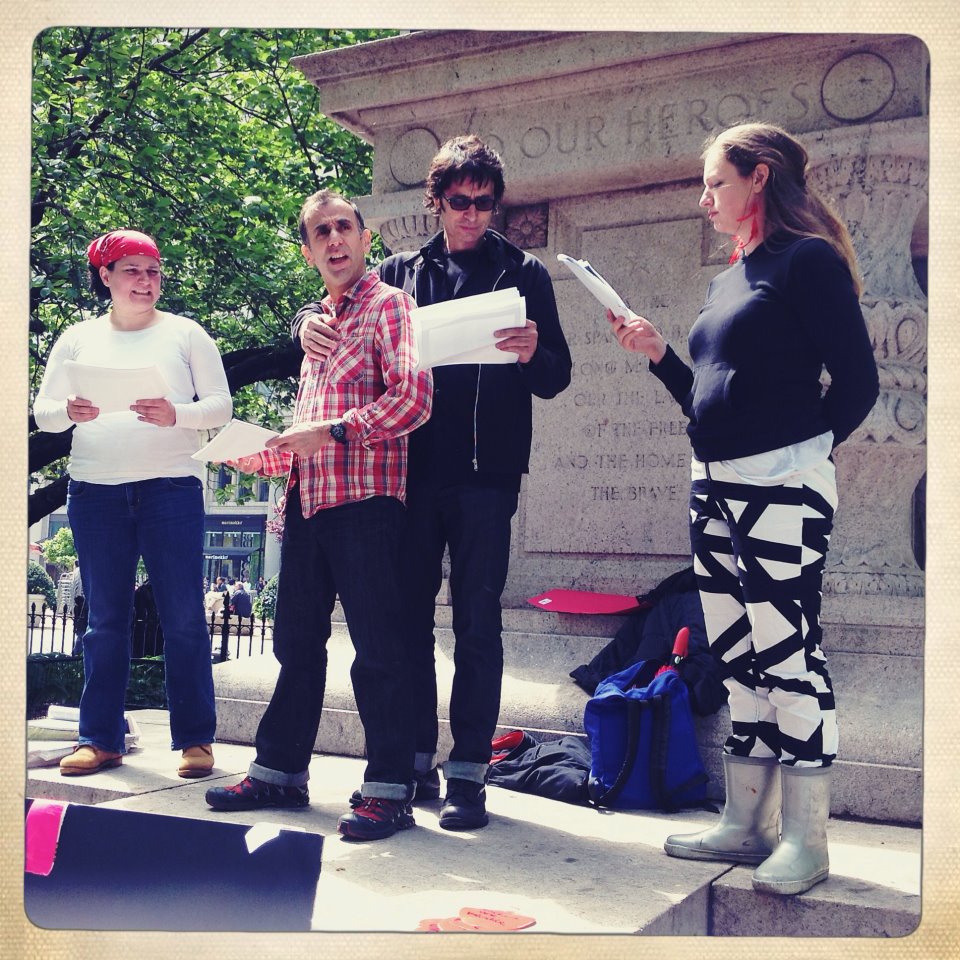

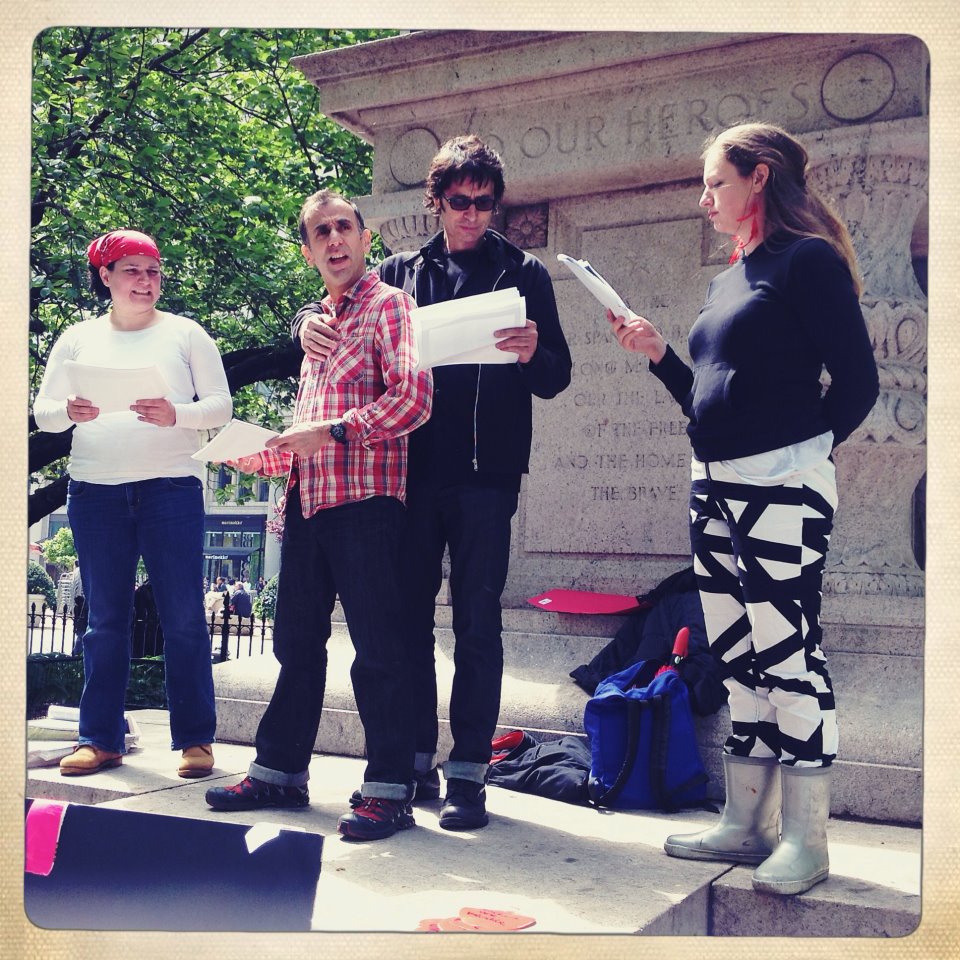

Then it was time for the Occupy Student Debt Campaign performance of “Can’t Pay! Won’t Pay!” on the steps of the flagpole. We had a mercifully sympathetic small audience and a great time was had by all.

Can't Pay! Won't Pay! With Niki Kekos, myself, Andrew Ross and Clare Lebowitz. Credit: Fulana de Tal

Even as we were having fun, David Graeber was addressing a substantial crowd, when the convergence march from Bryant Park arrived. Bryant Park was the site of many more picket actions, Mutual Aid, the OWS Library and other events, led down towards Union Square by the Guitarmy, a huge group of guitarists co-ordinated by Tom Morello. The Guitarmy scooted past us at speed–who knew musicians could move that fast?–followed by the main march.

We poured out of Madison Square Park to join them, giving the combined marches enough presence to take the street on Broadway.

Broadway and 17th, about 3pm

OWS Direct Action were co-ordinating this stage of the day very well and had sufficient control to organize a sit-down, not as a protest, but to slow the march so that those further back could catch up. During this pause, I spotted David Graeber using the opportunity to take pictures:

Graeber in brown leather jacket

Nice to know that even the famous activists like souvenir pictures as well as the rest of us;) And I’m mentioning these well-known figures here as a riposte to the suggestion that Occupy is now a rump of Black bloc anarchists and homeless people. This was one of the most beautiful parts of the day. Occupy activists were everywhere, the chants were loud and energizing and when we got to Union Square there was a May Pole, poetry and arts, it was like an alternative festival.

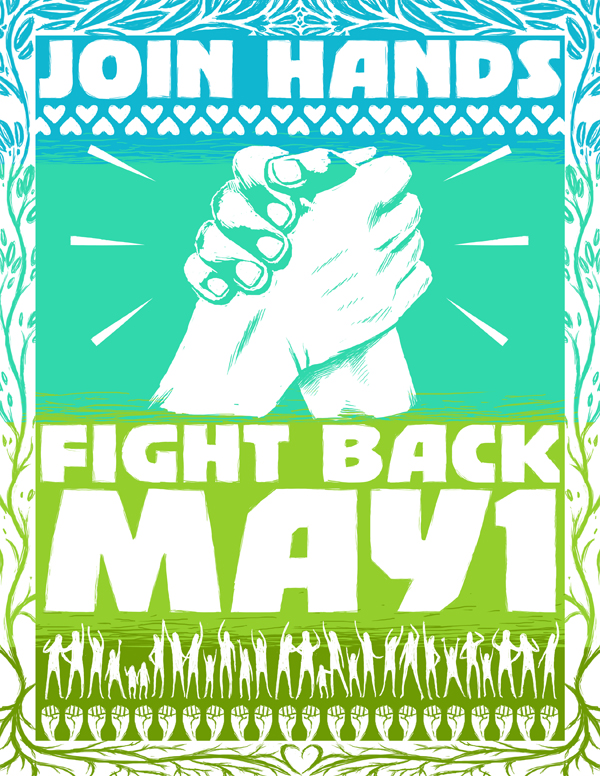

May Pole in Union Square

This traditional May Day celebration had been re-purposed to activist ends (or more exactly un-depurposed because it was an activist tool in the 18th century). On the top it says: “All Our Grievances Are Connected.” Each ribbon of the pole has an issue written out on it and as the dancers process around the pole they are interwoven. The May Pole reappeared later in the day at the People’s Assembly with its slogan high above us in the night.

It was sunny, hot even, by now and there was so much good energy around this section. Something of a lull followed, as we waited for the union contingents to arrive and for the rally at Union Square South. My subjective impression was that when the SEIU 1199 march and other locals arrived, they seemed much smaller than expected. Later in the day, other activists confirmed that impression. I passed the time handing out copies of the (free) fabulous Occupied Wall Street Journal, which was simple because people were so keen to get it.

Finally (as it seemed), it was time to march and I ran into my group from Occupy Student Debt. Here the long police preparations came into play. Although we left Union Square on the South side, we were immediately routed back north up a tortuously slow kettle of barricades, through a narrow bottleneck into 16th Street going West, all the way over to 5th Avenue, finally going south, but then back into another bottleneck on 13th St. The police made their intentions clear: they were not going to arrest people and give us a headline like Brooklyn Bridge last October. But they were going to try and break morale, depress people and take the edge off our mood.

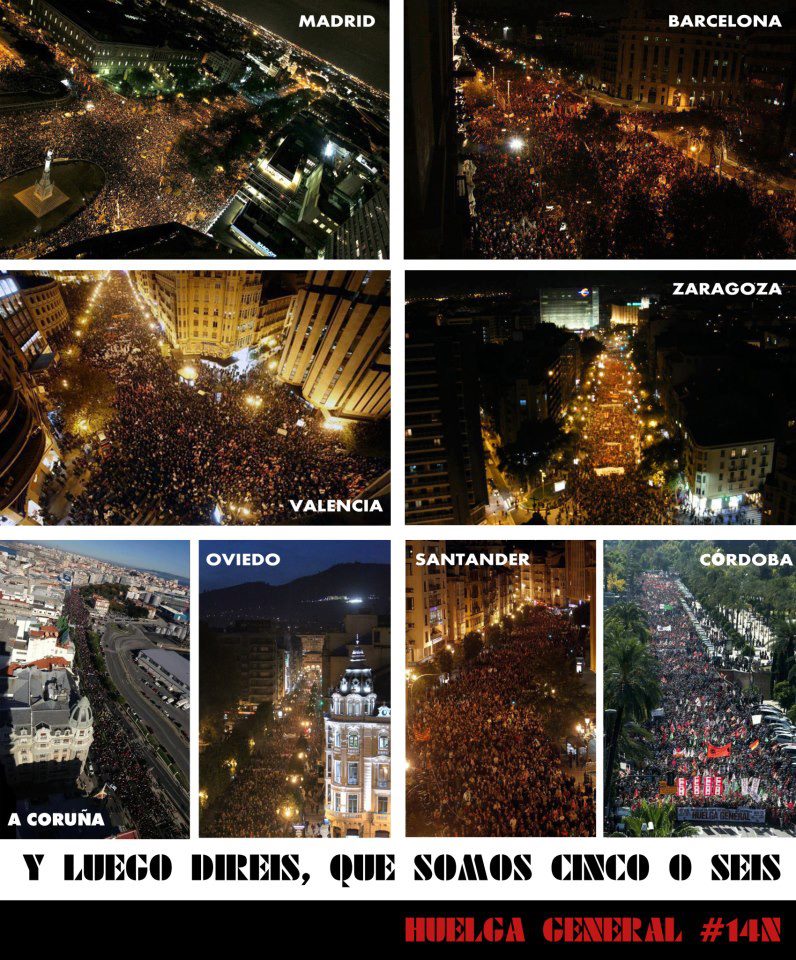

I’d have to say they somewhat succeeded until we finally got moving on Broadway and you could see how many people there were out. The Guardian‘s aerial photo gives you a sense of this:

Credit: Guardian newspaper: note OWS banner at the front

Estimates of numbers are always more of an art than a science. Twitter posts announced that there were still people leaving Union as we passed Wall Street. The free newspaper Metro, which, unlike the New York Crimes, actually put the march on its front page, estimated 15,000 which feels about right. Importantly, unlike October 15 and November 17 last year, most of those people were Occupy people. As I said, the unions did not turn out as many as was hoped and they seemed to disperse early on, with important exceptions like the health care unions, who were fabulous. From being an activist group that relied on existing organizations for numbers, Occupy is now a mass organization, which relies on older groups for permits and facilities like sound and stages.

As we got further downtown, carrying the Occupy Student Debt banner most of the way, the march became more of an Occupy celebration. I caught up with the main Occupy banner, which was a giant blue tarp, donated during the encampment. It had a long slogan painted on top but no one seemed sure what it said. Underneath the tarp, people discussed the day so far and plans for the upcoming People’s Assembly.

Direct Action discussion under the OWS banner

Again and again, though, we stood idly as police halted all marchers. As I passed Trinity Church, rumors circulated via Twitter that the police had broken the march in two. With the location of the Assembly at Vietnam Veterans Memorial Park on Water Street now circulating, people dispersed in various ways from the official route to find the park.

I entered the space with Andy from the Yes Men and it was one of those magic Occupy moments. Hundreds of people filled the bowl. A group of women from Occupy, led by Marissa Holmes, called the Assembly to order by People’s Mike that needed up to five relays to reach everyone. That sound, the murmuring of each phrase getting fainter as it retreated from where I was sitting close to the front, was very moving, exhausted as I was.

The People's Assembly, May Day, NYC

We were seated in between two towers, one belonging to the all-powerful ratings agency Standard and Poors, the other to mega-bank JP Morgan Chase. It was a good place for Occupy Wall Street, a good site as some began to think to occupy Wall Street. The bat-signal fired overhead.

99% Bat Signal

It was announced that this was the largest assembly held during the Occupy movement (I assume this meant in New York), and it was certainly the most extended I’ve seen, with dozens more sitting outside the main space, unable to get in.

Discussion turned to tactics. Whether planned in advance or spur of the moment, the proposal was that there be an attempt to occupy the park. Zach introduced a group from Veterans for Peace, who, appropriately enough given the nature of the park, were to blockade the police. Clergy arrived on a peace-keeping mission. Energy flowed.

At once, it seemed, Twitter and text feeds lit up with messages that hundreds of riot cops were outside on Water Street. It was announced that the park would legally close at ten pm and reluctantly, mindful of my green card status, I looked outside. I’ve never seen so many police anywhere, including during the miners’ strike in the U.K.

Police preparations on Water St

Those buses are empty, two of about six I saw driven up by the NYPD for mass arrests. Time and again, it has been pointed out that it is illegal for the police to use public transport vehicles as arrest wagons but the very point of their actions is to insist that there is only one authority in NYC.

Behind me, the Assembly took the decision to leave, rather than be arrested en masse. A few arrests did follow, inevitably, and some people found their way into Zuccotti Park. I’m not sure what happened overnight but I myself was very deeply asleep. Perhance, to dream of a better future.

Like this:

Like Loading...