As Occupy activists shake the May Day dust off their feet, the real discussion and decisions over “what next?” are beginning. The calls for global actions are becoming less rhetorical, more substantive. There’s a new form of Occupy emerging, as long assemblies and meetings gather to discuss strategy, tactics and goals in the context of the ongoing global social movements. While the Occupy strategy is of necessity intensely local, its reactivation of the popular claim to public space in conjunction with the European crisis and the continuing Arab revolutions has set in motion the possibility of a globalized countervisuality.

Here’s two report backs from discussions about the movement in New York and in Cairo and how they might relate or interact.

Yesterday, Occupy Theory called an assembly in Washington Square Park on the first hot day of summer. About twenty-five people came and others were drawn into the circle of the discussion as it carried on: unlike the heavily-policed Zuccotti, you can sit down in WSP and no-one seems to mind. It’s the hippy park, after all.

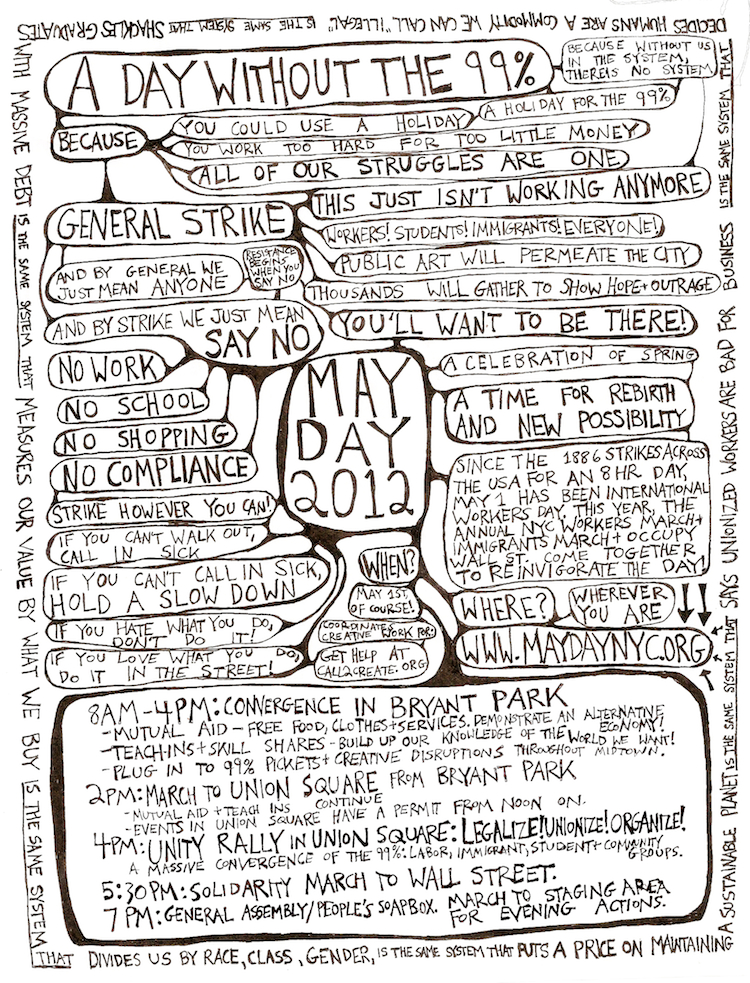

Facilitated by Marina Sitrin, the discussion at first reviewed how people were feeling in general about the movement. There was some expression of unhappiness with May Day’s direct actions, and there were some feelings that without Liberty Plaza, the movement is without direction. Against that, there was a sense that this is a different moment to last September and that horizontalism needs to be reconfigured, that we need to learn from Greece, Spain and Egypt.

A particular turning point was David Graeber’s observation that the real question going forward might be preparing for another, perhaps still more serious collapse of global capitalism. Sure enough, today we’ve seen a wave of nervousness concerning the Grexit–the Greek exit from the euro. That is to say, it’s not so much a question of formulating “demands” in this time of rapidly accelerating change as deciding what principles might guide our choices. There was a stress on developing mutual aid as a form of direct action, in addition to the idea of horizontal learning as direct action.

It was decided to hold a set of thematic assemblies on the Spanish model on successive Sundays. The first one next week will be on climate change and the commons, I’m pleased to say–more on this soon.

Today at the CUNY Graduate Center, an activist from Cairo named only as Mohammed shared his experience of the revolution. As always, you’re struck by the difference in scale at first. Going to a march with hundreds of thousands, seeing people carrying materials to build barricades, or using motorbikes to deliver Molotov cocktails are obviously not daily events in New York. As the discussion continued, I began to see how such distinctions could obscure some important interactions and interfaces of the global movement.

Mohammed mentioned that Tahrir had been designed to be accessible to colonial troops by the British, which also enabled the popular takeover in January 2011. He also suggested that even under the dictatorship there was a certain subcultural street life that was independent, such as the football Ultras whose experience in fighting the police was so crucial in the revolution.

I wonder if there’s a certain fluidity built into the colonial city that paradoxically allows for at least the possibility of the “classic” revolution? Whereas the dispersed, neoliberal, hyperpoliced urban environment requires that (re)claiming public space be the first step towards establishing the possibility of social change? So what is unique about the post-2011 movements is that these challenges to the established sense of authority have coincided, interacted and produced a new sense of the counter-global.

Indeed, as different as Cairo’s revolution was, Mohammed expressed a familiar frustration about the difficulty in sustaining their struggle against a very unified enemy prepared to use whatever violence is (from their point of view) necessary and the move into a “war of positions.” Periods of intense activity are followed by quieter times. Guerrilla art actions have emerged, like women artists holding discussions about sexual harassment in subway cars when denied official space. I don’t think that Occupy and the Egyptian revolution are the “same,” of course, but that, despite the differences in intensity, the different struggles against neoliberalism are paradoxically becoming similar.

In the discussion, these possibilities were drawn out. If there was a focus on the place of neighborhood and local actions from the Occupy side, that is because the more public space is reclaimed as popular space, the greater the sense of disruption to neoliberal business as usual. Then the idea emerged to link Cairo and Tokyo activists over the moving of the IMF meeting in October from the former to the latter–or as it was wittily put, “from revolution to radiation.” It seems that neoliberalist functionaries are running out of places to congregate, that the reclamation of public space has rendered all global cities with Occupies (that is, most of them) so politically toxic that the bankers prefer real toxins.