Yesterday began a key week of anniversaries: on March 11, 2004, known as M-11, the response to the Atocha Station bombing prefigured the indignados. March 17 is the six-month anniversary of OWS. And March 18 is the 142nd anniversary of the Paris Commune, which in some sense began it all. So this week I’ll think about these moments and some conceptual links between them.

To refresh the memory–several trains in or approaching the Atocha train station in Madrid were bombed simultaneously, causing 191 deaths and approximately 1800 injured. The atrocity occurred three days before national elections, in which José María Aznar’s conservative Popular Party were hoping for re-election despite their unpopular involvement of Spain in Iraq. Aznar held the Basque separatist group ETA responsible for the attack. However, it quickly became clear that an al-Qai’da inspired group had in fact carried it out. In the face of mass demonstrations, Aznar was defeated and the “socialist” PSOE were returned to office.

For Amador Fernández-Savater, the events of M-11 represented:

the emergence of a new form of politicisation which, summing up:

– does not necessarily have its meaning in the left/right dichotomy

– does not find its strength in ideology, so much as in first-hand feelings

– does not delegate representation or let others accumulate power at its expense

– thinks with its body and asks questions about meaning

– produces its own knowledge

– makes no attempt at cohesion, but at recreating the communal: an open, all-inclusive and joyful ‘we,

– transforms the map of what is possible

– does not declare another possible world, but fights to stop the destruction of the only one there is (We were all on that train).

The prefiguration of the indignados of 2011 and the related project of Occupy is striking. Equally significant, however, was the strength and speed of the popular refusal of the official explanation, drawing on the long experience of anti-fascism in Spain and the pervasive anxiety post-1975 about the possible return of dictatorship.

In very different vein, the young American writer Ben Lerner recently published his first novel Leaving the Atocha Station (2011). A quick plot summary: a latter-day Holden Caulfield wins a literary fellowship to Madrid after leaving Brown, where he seeks literary, sexual and artistic experience without success, despite being present during M-11.

The writing is intensely self-reflexive, doubling back on its every reference. There are extended passages close to Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, a somewhat redundant interspersal of photographs in the manner of W. G. Sebald, while the political events are kept adjacent to the narrative in the classic manner of Stendhal. Even the title is a reference to a 1962 poem of the same name by John Ashbery that famously resists attempts to give its pictorial style meaning. It’s the kind of book that adapts the author’s own critical essay on Ashbery for several jarring pages.

Unsurprisingly, the narrator Adam Gordon wonders about applying for literature PhD programs: it’s really the other way around, this is a book designed to have dissertations written about it. At the same time, it’s engagingly written and the anti-hero “portrait of the artist as a young man [abroad]” works well in this endlessly referential context.

Without pretending to review the book as a whole, what I was wanting from it was some account of M-11. One of Adam’s love interests, Teresa, was an active participant but he himself spends more time online, taking anti-anxiety medication and sleeping during the decisive days. Here the book wants to have it both ways, like similar “year abroad” first novels such as Indecision by Benjamin Kunkel and Prague (actually about Budapest) by Arthur Phillips.

Each wants to reference major political events, which Lerner ironically calls “History,” while maintaining a suitable distance. Lerner has Adam give a talk in which he says: “No writer is free to renounce his political moment, but literature reflects politics more than it affects it.” It says something about the book that I felt I had to Google the sentence to be sure it was not a quote from somebody else. For all the arch knowingness, it’s a very old-fashioned reflection theory at work here–that “art” reflects “the real” but cannot engage with it directly.

For all that, I came to think that this failure to engage was precisely what we can learn from Lerner (pun intended). That is to say, during the Iraq war so much Anglophone political discourse was centered on the Bush-Blair axis that many of us missed the importance of M-11 as a long-term rethinking of the political. While my own Watching Babylon, finished in May 2004, was revised to take account of the Abu Ghraib photographs released in April of that year, I only referenced the Spanish events. On the one hand, we were too convinced of the importance of the photographs as “evidence” that might convict the entire war project and, on the other, our “context” was still too focused on the Anglophone.

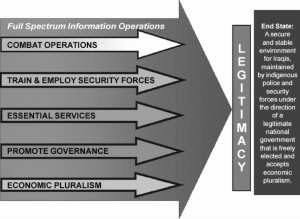

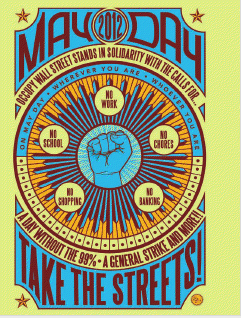

Occupy has, by contrast, repeatedly tried to learn from Argentina, Spain, Greece, Egypt and other forms of planetary resistance to the crisis–imperfectly, no doubt, but as the Spanish example shows, new forms of politics in the widest sense used by Rancière and Fernández-Savater, are built over decades not weeks.

On this anniversary, let us not forget that the crisis continues to intensify in Spain, despite huge swathes of cheap money deluging the banks and bond markets from the European Central Bank. From a recent report by Reuters, here are a few details:

street cleaners, nurses, teachers and job trainers are struggling to get by as cash-strapped local authorities withhold wages….In more than 1.5 million Spanish households, not one family member has a job. Almost half of adults under 25 are unemployed. Close to a third of the 17-nation euro zone’s jobless live in Spain….Spain’s 17 autonomous regions are laden with around 30 billion euros in deficit — 3 percent of the country’s economic output

The Financial Times has called this renewed austerity on top of recession “insanity” in the sense that doing the same failed action over and over again must be insane. Half a million people went to the streets on February 24 to protest this nonsense.

The M-11 and M-15 movements are not done yet. This is an anniversary, not a memorial.