That, of course, is the election slogan that never was. As Hurricane Sandy meanders over towards New York, the streets are so deserted, you half expect to see tumbleweed. After an endless campaign, we face the farce of a huge climate-change generated weather “event” that no one can name as such, because the issue has become unsayable. The canard is that to discuss climate disaster will scare the low-information voter. Let’s look at why that’s wrong and why the political establishment has closed ranks anyway.

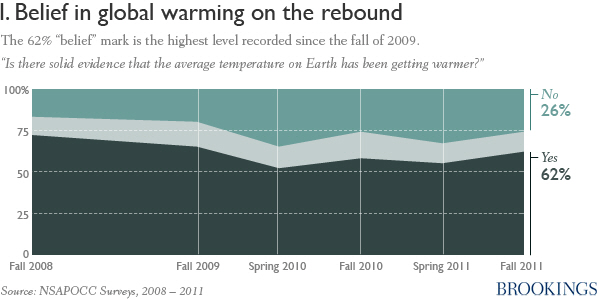

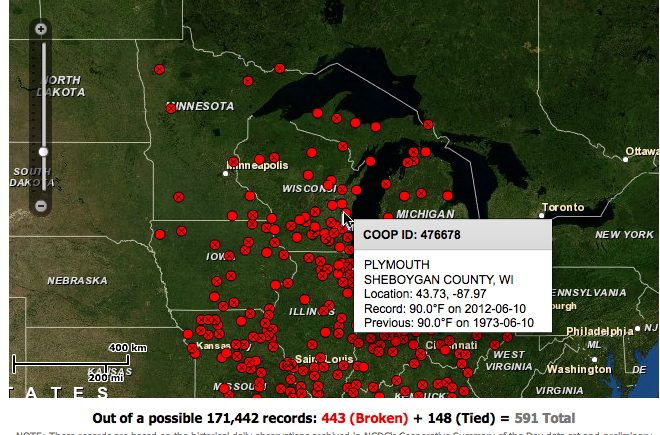

The Serious People in Washington tell us that there is no consensus on climate change or action to deal with it. Wrong and wrong. It’s true that around the time of the 2008 economic crisis, popular sentiment placed far less value on the issue. But that has notably rebounded since as you can see from this chart.

So while agreement on the settled scientific consensus around global warming did drop, it never fell below 50% and is now at 62%, perhaps the greatest majority around an issue tagged as “Democratic” or “progressive” that there is, other than on reproductive rights. Nonetheless, even the new-fangled moderate Mitt Romney did everything short of actually eat coal and drink crude oil in the first debate, prompting the always timid Democrats to back off.

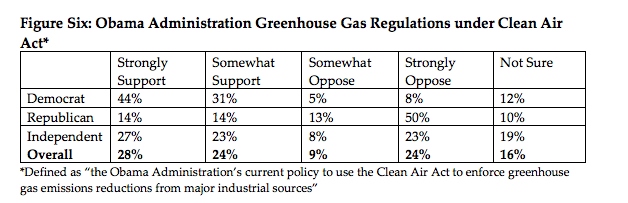

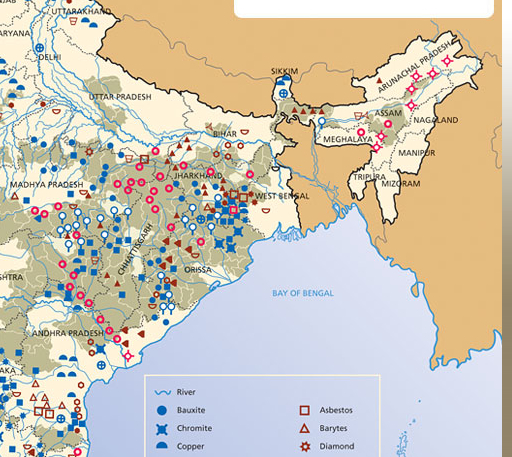

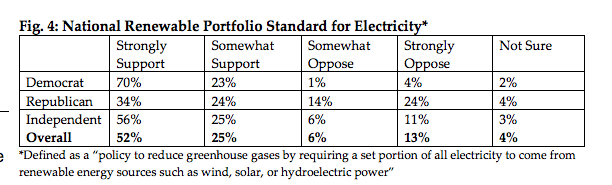

But the Brookings Institute report on climate change action options published in June 2012 shows how it would be possible to claim that majority for climate-related policy. It’s true that taxation and cap-and-trade schemes are not popular. But other options remain.

Here 77% of respondents, including 58% of Republicans, support requiring electricity to come from renewable sources. That’s a Senate-proof super-majority!

And a 52% majority (75% D /28% R) support the existing policy of using the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon emissions. So there’s no need for Democrats to obfuscate the issue, one on which a clear divide exists between the two parties, so much so that 90% of oil company campaign contributions, which are usually carefully divided between candidates, has gone to Romney.

So why has the issue been so comprehensively back-burnered? There’s a dark corner of think-tank and government activity called climate security. This purports to measure the impact of climate change on national security. So climate security types have a different assessment of the situation than most people.

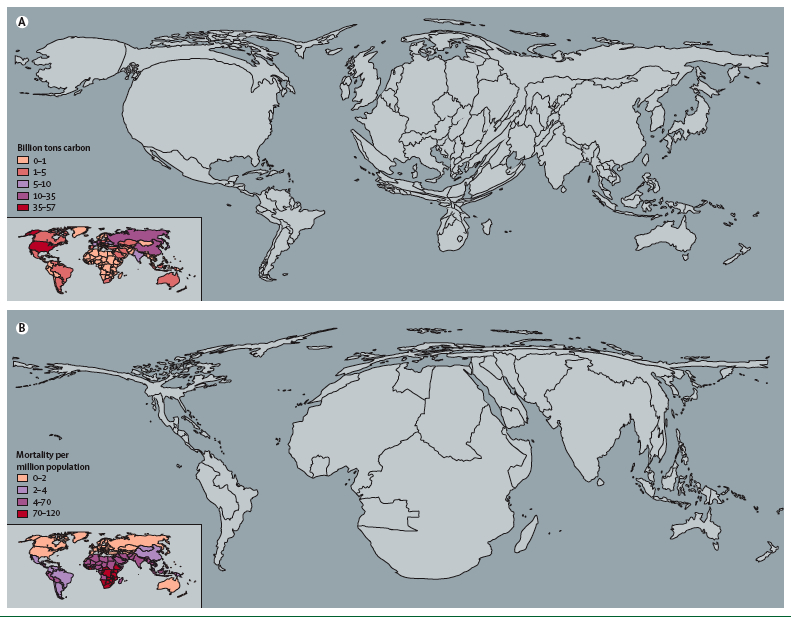

This diagram is taken from the British medical journal The Lancet. It shows, on top, countries mapped by quantity of carbon emissions. The United States is huge, while Africa is tiny. The bottom half maps countries by likely mortality due to climate change generated events. Here Africa becomes huge, whereas the US all but disappears.

There are those in climate security who see this kind of disparity as a form of strategic advantage to the US, despite the many issues of migration and disruption that are expected. In short, then, some in the US military-industrial complex are willing to let this kind of scenario play out for the strategic gains it entails. To be fair, others are not. But there’s a funny way that the most cynical view tends to win out in such circles.

The Lancet based its diagram on the 2007 IPCC consensus that a 3-4 degree rise in temperature was what could be expected. Since then, global efforts at CO2 mitigation have largely failed, emissions have risen to new heights and the feedback loops appear to be more virulent than had been expected. Translation: it’s much worse, much faster than was thought in 2007-9. US mortality rates are still going to be a lot lower than Africa’s, but drought, flood, fire and hurricane is not exactly what the term “security” suggests.

We know how to deal with this. It would mean a decentralized, demilitarized and de-industrialized way of life. Sounds good to me. And it may be something that people will be more willing to talk about if the New York city subway floods. Already the expectation is billions of dollars of damages. If we had spent that money on renewables and research back in 2007, perhaps this wouldn’t be happening. It’s not too late. But don’t look to our defunct electoral system for the solution.