From Italy, Britain and rural Pennsylvania, a triangle of the abuse of authority fills the news. The appalling allegations against the British celebrity (now deceased) Jimmy Savile now run into the hundreds. The leering Silvio Berlusconi was finally sentenced to a jail term that, regrettably, no one should expect him to serve. And it was reported that Penn State students are divided over the ethics of the Sandusky case.

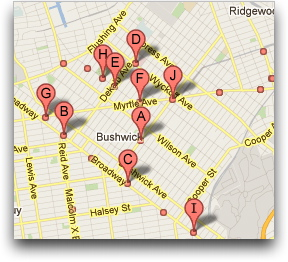

By now we have to see this as systemic. From the Clinton-era scandals to the Catholic Church, and the priapic fantasist of the IMF Dominic Strauss-Kahn to this latest wave of abuse, it’s clear that there is a consistency. In a perverse parody of the embodied claim to freedom represented by the Occupy movement, the neoliberal quest for dominance is being acted out on the bodies of those who everyone moves past and fails to see–the orphan, the sex worker, the disabled, the impoverished.

What is important to stress is that this has nothing to do with sex or desire. Dominance and submission as forms of pleasure depend, first, on the consistent possibility to end the play and, second, on the equal status of the participants. In the abuse of power, the abused have no such equality and are subject to verbal and media attacks if they speak up. This violence extends to journalists like Laurie Penny (@pennyred, a good friend of Occupy) or Suzanne Moore, whose thoughtful work on feminism and sexuality attracts amazingly vile comments: on the Guardian, Independent and New Statesman websites, note, not on some Tea Party discussion board.

In the university sector, an ethics class at Penn State is being taught around the Sandusky scandal. Depressingly enough, one student sums up the discussions on campus like this:

You either somehow support child abuse or you hate Penn State.

That’s reminiscent of the accusation of America-hating leveled against people bringing up the Abu Ghraib photographs, a discourse sufficiently successful that undergraduate freshmen at NYU this year did not recognize the photographs when shown them in class.

At Penn State, the discussions are lively around the case, pleasing the professor Jonathan Marks:

This was his role: to encourage, and promote, discussion. He never offers his opinion on the scandal, allowing the students to cultivate their own ideas.

Now, Marks is not quoted here and I suspect he might not put it quite like that. But the teaching strategy is familiar enough. I wouldn’t myself use it in this case because I don’t see an ethical dilemma here. It seems from the article that his intent was to give students ethical frameworks with which to analyze their existing tensions over Sandusky. Is that enough?

While these points may be salient, I have to recognize how abuse plays through academic life. In every department in which I have taught, male faculty members have approached me with comments about the attractiveness of some of the students. I’ve not joined the discussion or encouraged it but I have to realize that I did not forcefully condemn it. I eye-roll and change the subject. Again, to be crystal clear, I am certain that none of my colleagues engaged in abuse of the Sandusky kind.

As I write this, though, I now remember an incident long ago, in which the first discussion I had with a faculty member at an institution I had just joined was his request for me to sign a letter supporting him in a case of sexual harassment. He had tenure. I was a first-year assistant professor. I signed. I later met the victim and realized what a mistake I had made. Luckily, the university upheld her view and he was asked to leave.

What of Occupy? There were allegations of abuse, even rape, at the encampments. I never saw anything like that but I was not there overnight when the incidents were supposed to have happened. Do men claim too much authority, talk too much, always stress action over mutual aid? I wish I could say no.

This is an age of dominance without hegemony. Military power has failed to win the battle of hearts and minds in Afghanistan and Iraq. The wages of whiteness have been devalued. Certain men feel that their diminished authority must be acted out as dominance over the bodies of others. The impact of these rolling revelations is that such assertions of dominance cannot be limited to those negative spaces like the Army or the Church that radicals and liberals alike feel comfortable criticizing. It’s in media, in universities, in progressive politics and it’s not that we didn’t know but that we didn’t know it was still this bad. Or maybe that should be I didn’t know.

I just went for a walk. There was a fashionably dressed young man urinating against my building in full view of everyone at 10 o’clock at night.