How should we think of the past year? One way is to realize that in that time, any possibility of making serious changes to the global deterioration of the biosphere has dramatically receded. Whether you’re an environmental activist, a “that’s so terrible” headshaker, or an “it’s all about capitalism” person has become irrelevant. Short of major collapse, disaster or unforeseen events, we’re past the point of being able to do anything about this. What might get your attention is that the signs are that what worked for the climate issue is now being applied to capitalism–denial, displacement and legal enforcement.

The last surviving Pinta tortoise, Lonesome George, died in the Galapagos on Sunday. The species is now extinct.

If you have not been paying much attention, you may even not be aware that the UN Rio+20 environmental summit came and went last week. Rio was supposed to make good the promises of the earlier Earth summit and lead towards more sustainable development. The inevitable communiqué was dismissed as “283 paragraphs of fluff” by Greenpeace. Occupy activists did interrupt the closing ceremony to make a statement but were soon silenced. There was minimal media coverage and relatively little awareness in Occupy. When the COP17 Climate Change conference in South Africa collapsed in similar fashion early last December, there was a day of action at Zuccotti Park. Last week, as wildfires devastated Colorado, Arctic ice levels fell to record lows, and an early tropical storm flooded Florida, no comparable action took place.

Along with many others, I’ve been pushing this issue throughout this project to little effect. We did hold an Occupy Theory Assembly on climate. It started well but became becalmed in demands that we endorse a long submission to the Rio conference. Proposals for direct action against the fossil fuel industry were more promising. However, the idea of lying down in front of coal trains was a little daunting. It was not that people did not see the urgency of the issue but that they could not see how to make headway with it.

And here’s why. Yesterday, the US Court of Appeals in DC ruled against a suit attempting to prevent the Environmental Protection Agency from regulating green house gases. The judgment scathingly noted against the so-called climate skeptics:

This is how science works….The E.P.A. is not required to reprove the existence of the atom every time it approaches a scientific question.

However, the Republican attorney general of Virginia gave notice that he will appeal the ruling. Any guesses as to how the Supremes will rule on this?

On the same day, we learned that, despite the disaster in the Gulf, Shell Oil will get off-shore drilling permits for Alaska. What’s so tawdry about this transparent election-year vote grubbing from the Obama Administration is that not a single Republican or Independent that wasn’t going to vote Democrat will do so as a result of this move. But one of the few remaining pristine landscapes will be ruined and yet more animals will die.

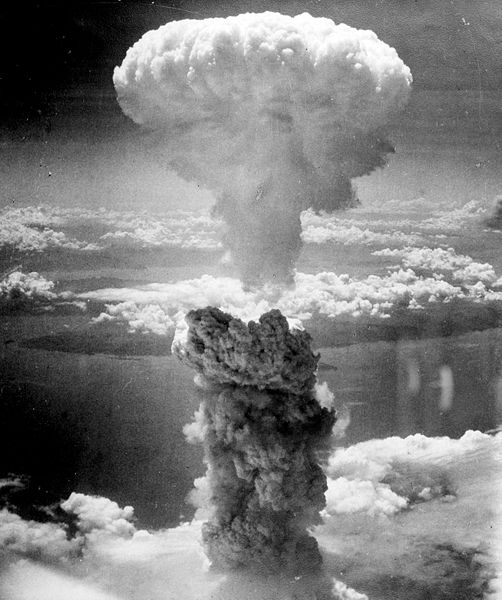

Humans are now causing what is known as the Sixth Great Extinction, a mass slaughter comparable to whatever it was that killed the dinosaurs, except that we’re doing it on purpose and we know we are. About 30,000 species a year are becoming extinct from megafauna like the Pinta tortoise to frogs. Insects are thriving and will inherit the planet.

Leave the disasters, extinctions, floods and fires to one side: we’ve got used to grey smog as the permanent condition in all the global cities, to a hole in the ozone layer, to holes in the floor of the ocean leaking oil, to the disappearance of drinking water, the spread of deserts and once-tropical diseases. If we’re ok with all this, do we expect debt and unemployment to generate a mass anti-capitalist movement?

For capitalism, this is all business-as-usual, what they like to call “creative destruction.” It’s also a new way to profit, as the wave of green-washing ads from oil companies makes clear. For anti-capitalists of all stripes, from the mildest reformist to the most wild-eyed revolutionary, our collective failure to develop anything other than rhetorical purchase on the survival of life is devastating. Not just to the biosphere, human and non-human life, but to the chances of pushing back neo-liberal capitalism.