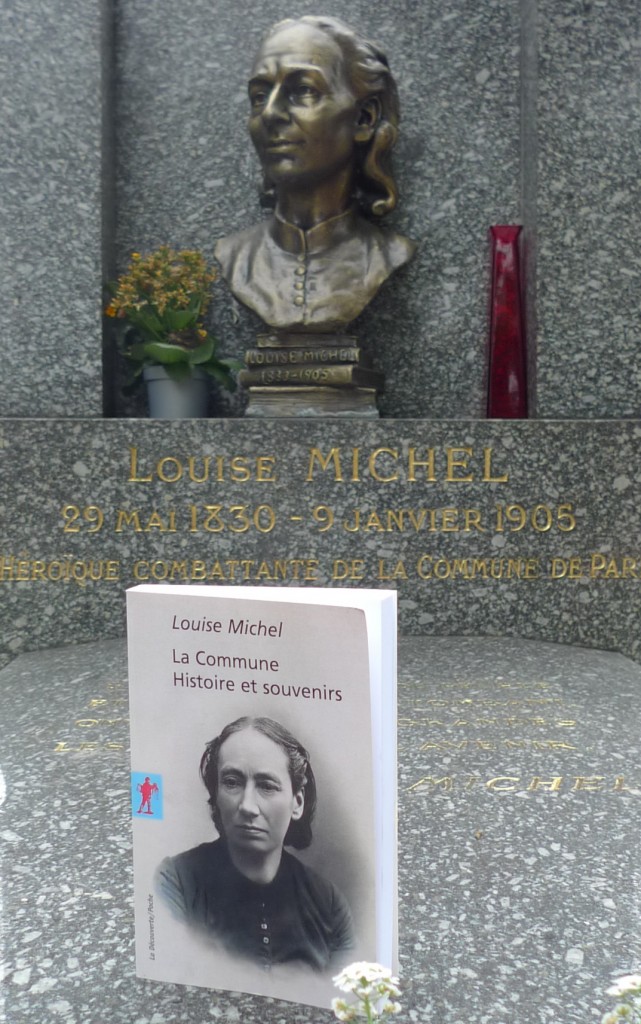

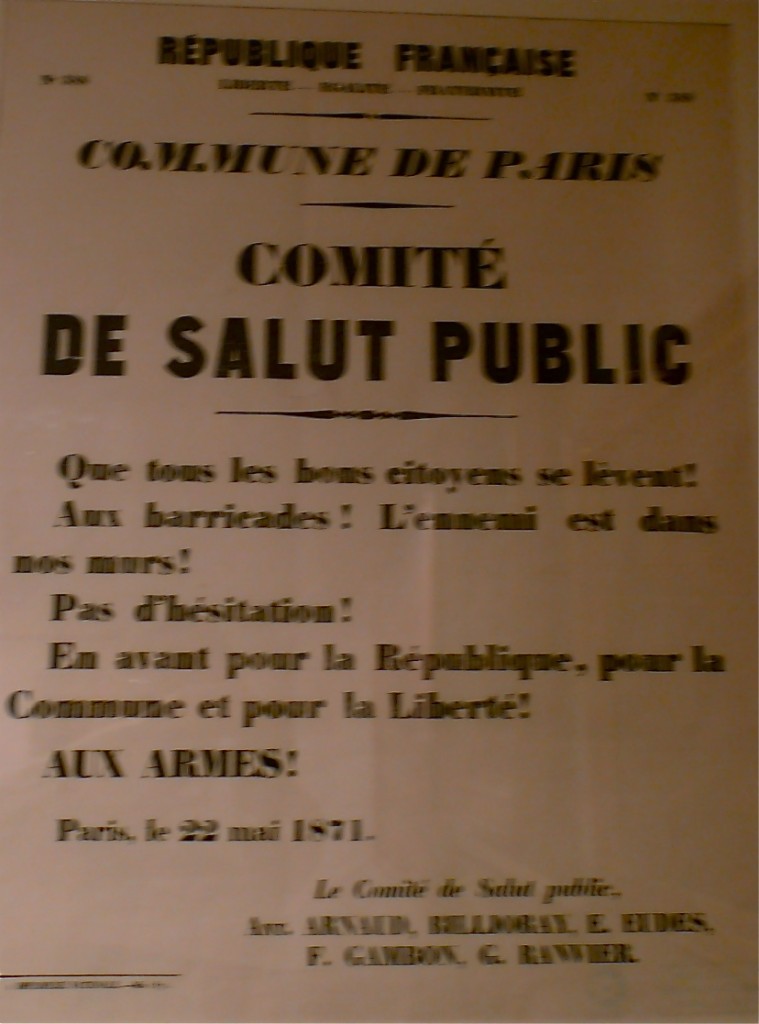

One night during the Paris Commune of 1871, Louise Michel found that she and an African veteran of the Papal Guard were the only two defenders of a key fort. To pass the time, he posed the question

–What effect does the life we lead produce in you?

–The effect of seeing a shore we must reach, she replied.

–Myself, he replied, it gives me the effect of reading a book with images.

These replies were in “reverse” order to what a certain modernism might lead us to expect. The African soldier gave a reply moving from print culture towards a cinematic imaginary, whereas the French poet created an image of a panoramic landscape that would exceed any one person’s capacity to see. These are deceptively simple images, then, by which to visualize what the Zapatistas would call the “walk” that the Commune was taking.

By contrast, the anthropologist James C. Scott has highlighted the way in which “seeing like a state” means a certain abstracting, centralizing vision. His first example involves seeing a tree simply as timber, compared to all the other known uses for the wood, bark and even leaves of the tree, let alone its existence as a living ecosystem.

How can we imagine seeing against the state, or better yet as a non-state? In a recently translated collection of the essays of Pierre Clastres, originally published in 1980 offers some perspective from that moment in the 1970s that seems to prefigure our own. Clastres was interested in creating a “political anthropology” and saw what he continued to call “primitive cultures” as being an “anti-production machine.” Rather than understand indigenous societies as pre-capitalist, Clastres presented them as radically different:

When the mirror does not reflect our own likeness, it does not prove there is nothing to perceive.

As in the example above from the Commune, the point is not to reduce alterity to a single image, as the state would do, but to multiply them.

In this sense, “primitive” society will always exist, as what Eduardo Viveiros de Castro calls

the force of anti-production permanently haunting the productive forces, and as a multiplicity that is non-interiorizable by the planetary mega-machines.

There is always, then, another possible world and it already exists and has existed for a long time. Clastres asks, if we set aside the hierarchical gaze of ethnography, “how are we to finally take seriously” societies where power is not associated with control?

In this question, there are two loud echoes. One is Derrida’s haunting question at the opening of Spectres of Marx: “I would like to learn how to live, finally.” Might we then understand that “finally” as meaning: at the end of the long Western metaphysic that has, since Aristotle, presumed that a separation of the political is the distinguishing mark of the human? Here the further echo is with Rancière’s concept of the “division of the sensible” that he tends to see as very long-lasting. To live, finally, without control would mean living in such a way that “the political” was not a separate domain.

Clastres points to the conquistadores, newly arrived in what they called the Americas:

Noting that the chiefs held no power over the tribes, that one neither commanded here nor obeyed, they declared that these people were not policed, that these were not veritable societies. Savages without faith, law, or king.

It’s easy to draw a parallel with the Commune and Occupy encampments, whose anti-production machines were held equally intolerable by the police of their own time. Less easy, but now more necessary, is to take that seriously and add what Philippe Pignare and Isabelle Stengers call “a sense of dread” to that comparison.

While it’s clear that Occupy might prefigure anti-control and anti-state ways of being to a certain extent, becoming anti-production (meaning anti-growth, anti-seeing-as-a-wealth-producer) and pro-sustaining, every day the work is at hand of enacting that seriously. In Argentina, some groups withdrew from confrontations with the state after 2001, according to Marina Sitrin, precisely to develop such possibilities. In Greece, many local governments have collapsed themselves back into their communities, helping people to resist the new electricity tax surcharge to pay back the banks. That is to say, they have ceased seeing like a state.

In the US we’re a long way from that kind of crisis–but also from that kind of altermodern “primitivism.” Here we don’t want to replicate the capitalist frenzy against the very collapse of Greek society that they helped to create but to mark the multiplicity of viewpoints that are now tenuously available in the crisis. I’m not sure we can see that yet.

This week the island nation of Kiribati (pronounced Kiri-bhass) [above] announced that it is buying land in Fiji for its people to move to after their islands flood because of climate change. These “South Pacific” (actually West Central Pacific) islands have been the Western “vision” of non-productive but plentiful societies since the first encounter in the mid-eighteenth century. Without dread, we are standing by as they disappear. Not one print or television outlet covered the news. We can’t see this as here and now, only as there and then.

This week the island nation of Kiribati (pronounced Kiri-bhass) [above] announced that it is buying land in Fiji for its people to move to after their islands flood because of climate change. These “South Pacific” (actually West Central Pacific) islands have been the Western “vision” of non-productive but plentiful societies since the first encounter in the mid-eighteenth century. Without dread, we are standing by as they disappear. Not one print or television outlet covered the news. We can’t see this as here and now, only as there and then.

So it’s a great thing to see that M17, the six-month anniversary of OWS will feature a march to the memorial for the Irish Famine and a further challenge to Monsanto and global corporate food. More on that tomorrow. Seriously.