Alexis, A Greek Tragedy, a remarkable performance by the Italian group Motus, both investigated the transition to popular action and created a method for critical visuality studies to follow. The project creates a complex interface between, on the one hand, the theatrical Antigone and the historical legacies of her refusal to obey the law and honor the dead; and on the other, between the police killing of 15 year-old Alexandros Grigoropoulos in Athens in 2008 and the current crisis.

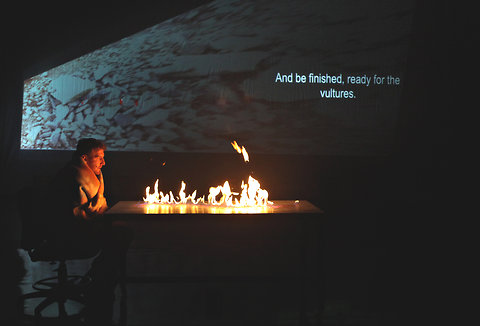

Silvia Calderoni/Antigone

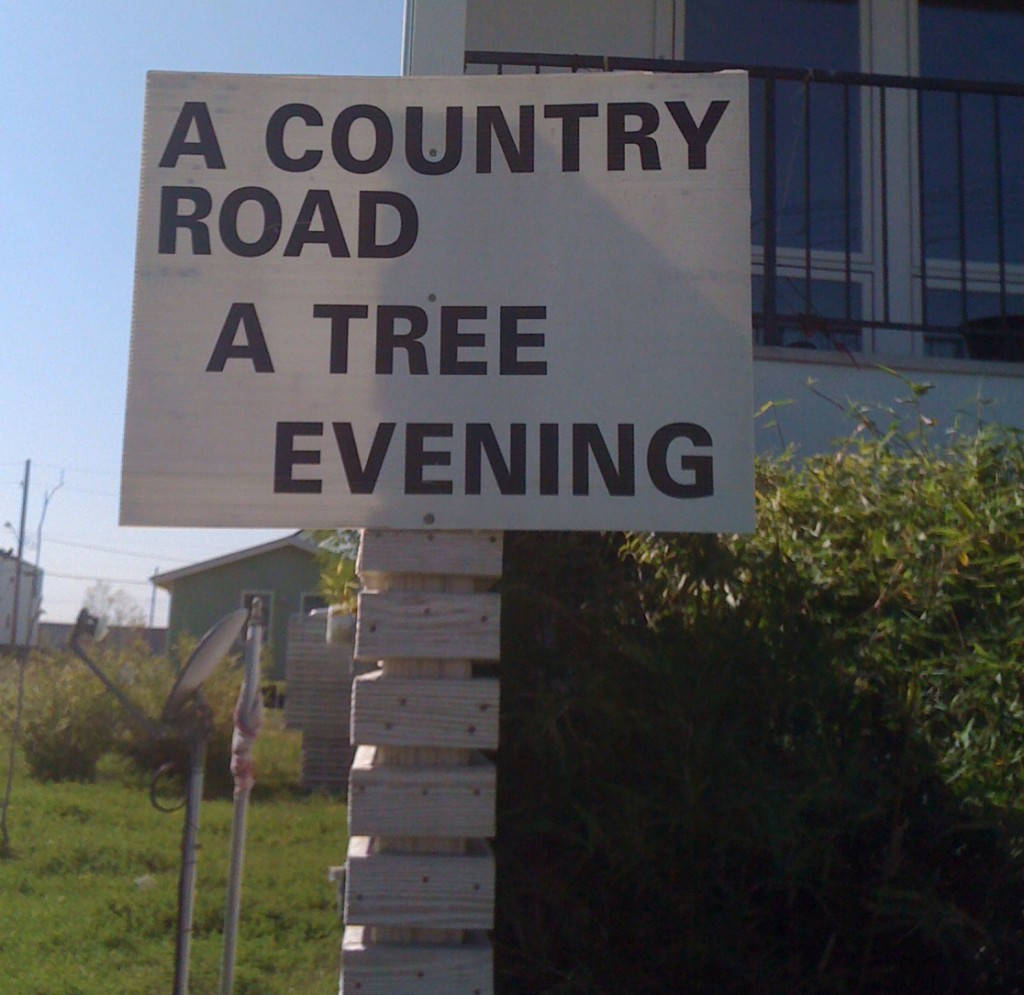

The result was expressed by the device of a square on the stage as the center of the performance space. It was taken to represent the square in the Athens district of Exarchia, near the Polytechnic, the long-standing center of resistance to the military junta. During the performance we were shown video of open public spaces in Exarchia like Nosostros, a performance/meeting/social space.

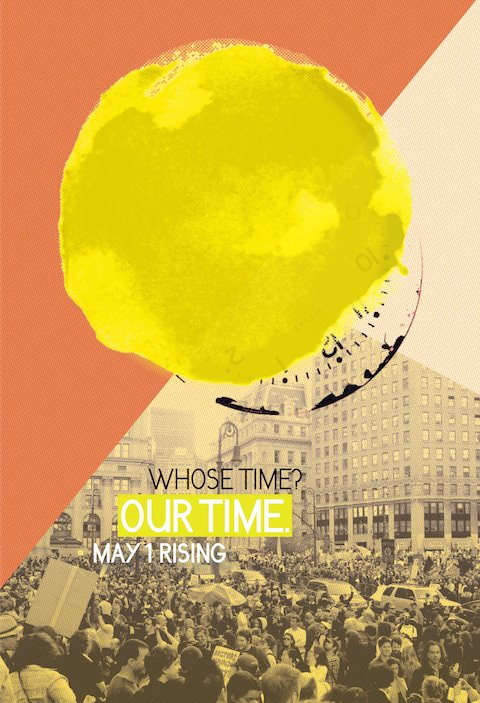

Alexis’s death on December 6, 2008 sparked what can be called an uprising in Exarchia that has now merged with the protests against the crisis to create a revolutionary moment in Greece. For Motus, the key question at stake is: “How to transform indignation into action?” The term “indignation” has been central to European Occupy projects from the Indignados in Spain to the Indignés in France. The key question here is the moment of transition and transformation in which that sense of frustration becomes concerted action. And then behind that is the question of what “action” properly means: how to move from refusal to something that is not a form of accomodation or replication with and of the status quo?

Ross Domoney’s video tells the story of the riots around Alexis’s murder and their interface with the current crisis.

Exploring Revolt in Greece from Ross Domoney on Vimeo.

Watching the film, there is a certain performative element as the police throw tear gas and the rioters throw Molotov cocktails. Although this is clearly violent and dangerous, the petrol bombs largely land short of the police and don’t hurt anyone. Many demonstrators came prepared for the tear gas as well. I do not mean to say that this is not “real”—what emerges is to the contrary a sense that the tension within Greece is under constant escalation and it is not clear what will happen next: “the waters are too dark.”

In short: how to visualize the square, the crisis, the movement? What’s coming next? As you know, my recent book has stressed the role of visuality in creating authority precisely by means of being able to engage in such visualizing and to apply force to sustain it. The word was coined in English by the conservative Thomas Carlyle, who wanted to see the military technique of visualizing the battlefield applied to the social as a whole. His “hero,” the great man of history, was Napoleon who first epitomized these qualities, according to Carlyle, when he turned his cannon against the Parisian revolutionaries in 1795 and mowed them down in the streets, preventing a radical journée, or day of action.

How do you countervisualize when your goal is not to mow down the other side in the street but to catalyze a sense of alienation into social transformation? In Alexis, a cross historical identification of the abandoned body of Alexis was made with that of Polynices, Antigone’s brother for whom she sacrifices herself. The widespread A for Anarchy in Exarchia was read as also signifying Antigone. Giorgio Agamben’s question: “what life is worth being lived?” is understood as a reading of Antigone’s refusal to submit to Creon’s law and the current questioning of ways of being.

The square was visualized as the interface of four projects:

- the interface of the ancient text of Antigone with Brecht’s interpretation and the historical legacies of the theme in Greece

- the multi-year performance of Antigone by Motus

- the already “historical” events of 2008, an event already forgotten by the media when the group began to investigate them in 2010

- the moment of Occupy, from Tahrir to OWS and beyond

The method that emerges here is fascinating. The interface of formal work and questions of technique or theory is one “side” of the square. The group discuss theatre technique with the audience, reveal some of their methods and invite the audience into the performance. The play reflects over and again on its conditions of possibility: how can a part be performed? How should the words, even the punctuation, be rendered? Should an actor playing dead body have his mouth closed or open?

This interface was redoubled by the remarkable physical theatre: the performance opens with Silvia Calderoni edging across the stage, one half-step at a time, and at each step, jack-knifing her body–it was a stunning depiction of the pointless frustration of mundane labor under the Law. Calderoni brought the physique, self-possession and technological skills of Lisbeth Salander to Antigone, while also managing to be a welcoming presence.

Double down: one “performer,” Alexia Sarantopolou, is a resident of Exarchia and expresses her skepticism as to whether events such as this can be rendered as art. I was reminded of the disdain expressed by the former revolutionaries who appeared in The Battle of Algiers, for whom the film was a “game” compared to what they had experienced. Calderoni agrees but then suggests that doing this work is all she can do, while stressing that the formal pretense that the “outside doesn’t exist” has to be abandoned.

So the performance describes and visualizes the events of 2008 and the space of Exarchia in detail, relaying visual images, interviews and film by means of projections from a computer and acting out their encounters. In Motus’s description:

the stage becomes the place of a choral presence, emotionally moving, which acts on a polyphonic and stratified text of a hybrid and lightning-swift nature: dialogues, interviews, solitary reflections, attempts at translation from Greek into English and Italian, audio and video fragments from the web, descriptions of atmospheres and landscapes, political statements and testimonies…

In this visualization, Antigone becomes the sound of Exarchia, the sounds of the revolt and the form of the transformation from subjected to subject.

Of course, it’s only a play. If you were to measure the success of the transformation by the number of people who accepted the performers invitation to join in their visualization of protest, you’d see only a small group–young Occupy types, older people of the all-experience-is-good variety, a few middle-aged hybrids like myself. Would a fully successful performance mean that there was no audience left? or does it mean accepting the immersive performative challenge inherent in the project: one of tarrying with the subject, one of staying with it after it is “current,” learning to countervisualize as we go?

For those few of you still reading, that’s what we’re trying to do here: a durational performative effort to stay with the moment, to understand what transition means and how to visualize it. Already the audience has dwindled. It’s OK. In fact it’s good. It’s all I can do.

Like this:

Like Loading...