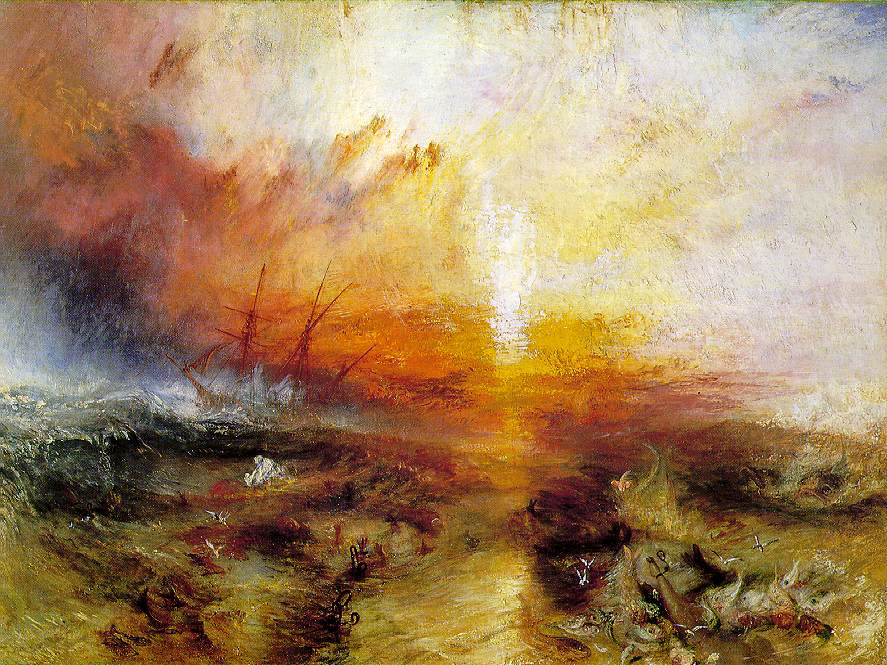

After Katrina, it was hot, freakishly hot. After Sandy, it is cold, ridiculously cold. There’s six inches of snow on the ground, howling winds. In Spike Lee’s classic When the Levees Broke, there’s a montage in act one of people saying over and over “it was hot.” Most people in New York and New Jersey who lost housing will be indoors tonight, so we may not get a parallel montage. But we’re only just beginning to understand what we’ve been through and are continuing to go through.

During MSNBC’s broadcast of the election results last night, a poll showed that 15% of voters rated the response to Hurricane Sandy as the top reason behind their vote. Of those people, 70% voted Obama and 30% Romney. It seems odd until you realize how little has been done because the scale is so much greater than we have fully realized. If you go to this link, you can see before and after aerial photographs of the coastline taken by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that make it clear that rebuilding is not a serious option.

NBC has been pushing the issue in its news partly because their anchor Brian Williams grew up on the Jersey shore and is still very attached to it. Over and again, middle-aged white men like Williams and Chris Christie, New Jersey’s governor, have been evoking their loss and nostalgia for a past that was in any case long gone. Obama toured with the crown prince of Jersey nostalgia, Bruce Springsteen, whose Jersey classic Asbury Park 4th July (Sandy), usually called just Sandy, has acquired an entirely new meaning.

This combination of a sense that Sandy indicated both what we now need to do, and what it is that we have lost, gave Obama his winning margin.

What will be done with it? Last night before tuning in to the results, I watched last week’s episode of Treme. By coincidence, it featured the documentary film maker Kimberly Rivers-Roberts, whose work in Trouble The Water was nominated for an Academy award. In a complex interplay of experience and fiction, the episode showed a group of the characters being drawn into watching Rivers-Roberts’ extraordinary footage of the waters rising in the Lower Ninth Ward during Katrina.

We then cut to her husband recreating the moment when they led a group of survivors to dry land only to be shot at by National Guard troops. These soldiers were nominated for bravery medals. In Treme, people who experienced Katrina play characters who also went through the storm, like Phyllis Montana-Leblanc, who came to national attention in Spike Lee’s film and has now become a Treme regular.

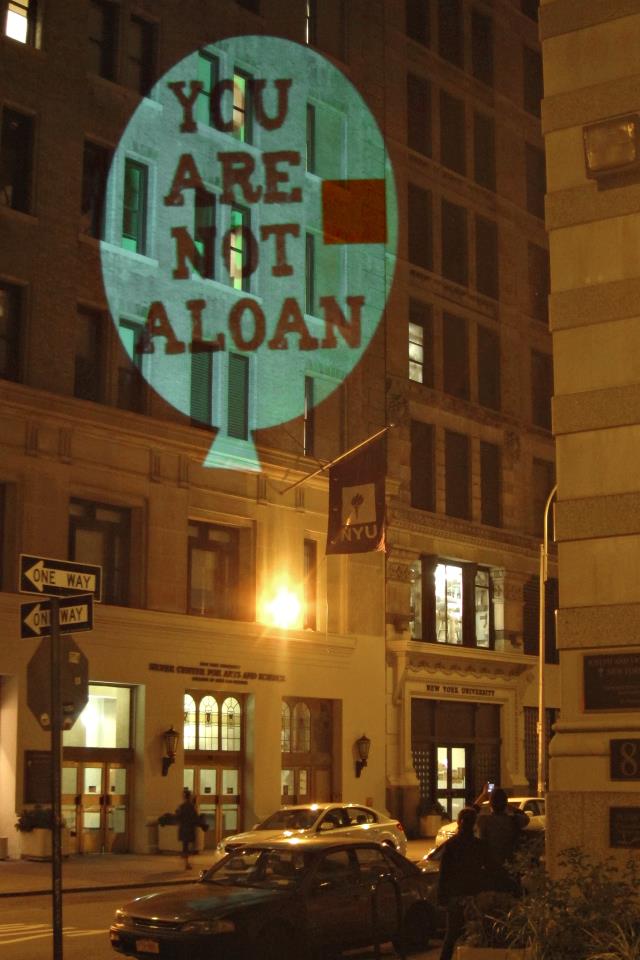

What such moments suggest is that there is no outside to the climate-changed biosphere, no retreat into a world of superhero make-believe. In his acceptance speech, Obama presented himself as a “champion” of those in need. Our system currently works that way. Today I called my re-elected congressional representative to complain that after ten days, my house had not been restored to electric power. A few hours later, the current was flowing.

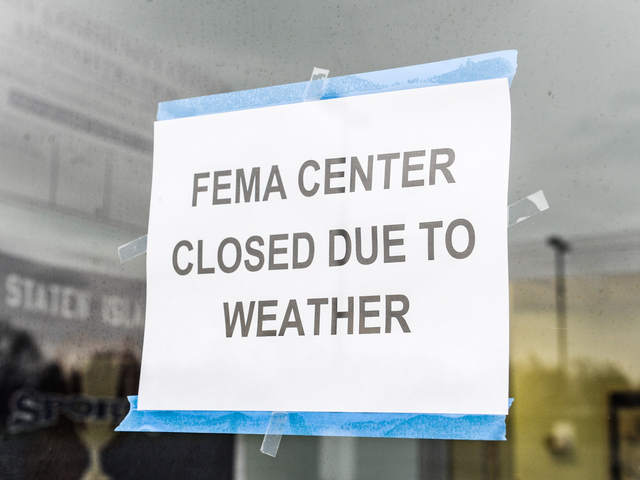

But on the ground, moments of heroism are rare, and champions hard to find. As the new ice storm blew into New York, this was what people in Staten Island saw at the FEMA office

As crazy as this seems, the makeshift shelters are no good against the driving snow of a Nor’easter. We’ve yet to recognize that as well as the broken roller coasters and carousels, the space shuttle Enterprise in New York was damaged, thousands of artworks in studios in Chelsea and Red Hook were destroyed, and so on and on.

We don’t need a champion in all this. We need to hear that the press release put out today by Keystone XL to the effect that they are “confident” that the northern sector of their pipeline to extract tarsands will be confirmed in January was wrong. We can’t wait and see how the new administration chooses to decide because for us, shivering in Sandy’s cold, there is no choice. From now on, no more nostalgia, no heroes or champions. It’s time for direct action.