There is devastating drought across about half of the US, caused by fossil fuel capitalism. The drought and resulting food shortages, price rises in basic foodstuffs and resulting inflation is likely to intensify the crisis of capitalism. There will be food riots in places where incomes are low and mostly spent on food. That may include parts of the fossil fuel intensive world, as well as the domain of the wretched of the earth. All the anxiety about the technicalities from CDOs to LIBOR may pale beside the fundamental crisis in producing food for humans and animals, should the drought continue.

The photograph above makes it clear that this set of circumstances is the product of a certain form of financial capital. The ostensible subject of the picture is the wizened corn, so dry that farmers would be delighted to salvage a third of the crop. Any neutral person is also going to want to know about that sign.

It indicates that the corn being grown is not “natural” but a proprietary product of Croplan by Winfield, number 6125VT3. This varietal is intended especially for use in the West. One of its alleged benefits is being drought-resistant:

Hybrids are selected for strong drought tolerance, even when planted at a high plant population. This is important in the western Corn Belt where low plant population is used as a hedge against drought.

Oops. Now you might think that this would lead to farmers not using these crops next year. But it’s not that simple. The seed always belongs to the supplier and contracts lock you in. The particular varietal shown drooping above is a test variant being tried out in various locations. According to a farmers’ chat site, Croplan

source their germ plasm from Monsanto, Syngenta, Pioneer, Mycogen

meaning the major GMO food monopolists. Croplan is part of WinField Solutions, the third largest seed company and number 1 pesticide outlet in the country. Both are owned by Land O’ Lakes, the dairy conglomerate, itself part of Dean Foods. As a result of these interfaces, Croplan is very keen on corn that is pesticide tolerant.

Again, the supposed benefit to the farmer is plants absorbing more moisture and nutrient.

So farmers have paid for expensive drought-resistant seed that didn’t deliver when really tested. The ramifications of this failure go in many directions. There are vast numbers of genetically modified varietals interacting with the existing seed population to unknown effect. It’s an article of faith among dog owners that GMO corn makes dogs allergic. What does it do to us? Food is becoming more expensive with food prices officially rising 4.8% in 2011 and likely to be much higher again in 2012. An economist with the Federal Reserve Bank in Kansas explains:

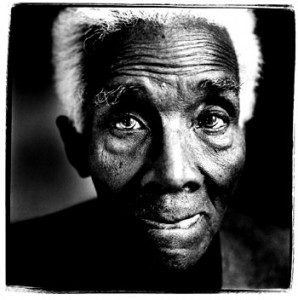

The impact of higher food prices is felt disproportionately by poorer Americans, Mr. Henderson said. For Americans in the bottom 20% of income, food typically takes up more than a quarter of household income, compared with about 10% for wealthier Americans.

So if food rises 10% in price over two years, you can be sure that the wages and salaries in the lower half of the economy have not risen to match. While the poorer will do worse, the corporate fear is that food will ignite inflation and reduce profits. Dean Foods, owner of the whole chain of corn and milk we’ve been discussing is down 22% in the stock market. I wonder if capital can survive another shock of this size, despite what Naomi Klein has called the “shock doctrine.” If the largest monopolies are struggling, who can take them over?

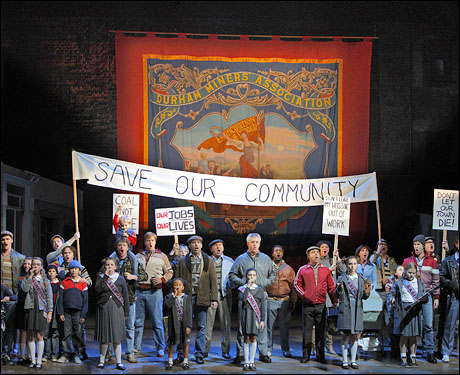

So climate change is not “just” a disaster caused by capitalism, which it is; but it’s also a disaster for capitalism. Last week, Via Campesina, the international land-use and peasants’ movement, concluded a successful conference in Indonesia. The Governor of West Sumatra returned expired land use contracts from corporations to ulayat (indigenous peoples/community rights). The final declaration called for the movement:

to incorporate other peoples who are threatened by the same current phenomena, including urban dwellers threatened with impoverishment and with eviction to make way for real estate speculation; peoples who live under military occupation; consumers who face ever higher prices for food of ever worsening quality; communities facing eviction by extractive industries; and rural and urban workers.

I would say that sounds like an agenda I can agree with, wouldn’t you? More than that, it sounds like the agenda we need.

![yrs in debt 2]](http://www.nicholasmirzoeff.com/O2012/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/yrs-in-debt-2.jpg)