There are things going on. Learning is changing even as the debt apparatus tries to commodify the entire process into what it probably wants to call something like education capital. In the quiet of summer, some events emerge to show us what is to come (à venir) and that the future (avenir) is now. The àvenir is the future to come. It is Montréal. It is Free University. It is the Interference Archive. It is now.

The AVENIR piece above is the work and concept of a young group of Quebecois artists, who call themselves Ecole de la Montagne Rouge, the School of (the) Red Mountain. Their name evokes both the legendary Black Mountain art school and the Mountain, as the most radical faction of the French Revolution were known. EDLMR articulate a philosophy of radical learning:

We and thousands of other students across Quebec believe that education is a right, not a privilege reserved for the well-off. The tuition increase jeopardizes access to higher learning for our generation and future generations. Sensing that an unlimited general strike is looming, many protest movements and pressure tactics are being organized across Quebec. This is an opportunity for all students to show solidarity, defend our points of view and get involved so that we can create a balance of power in relations with the government. Our victory depends on the daily efforts made by each and every one of you.

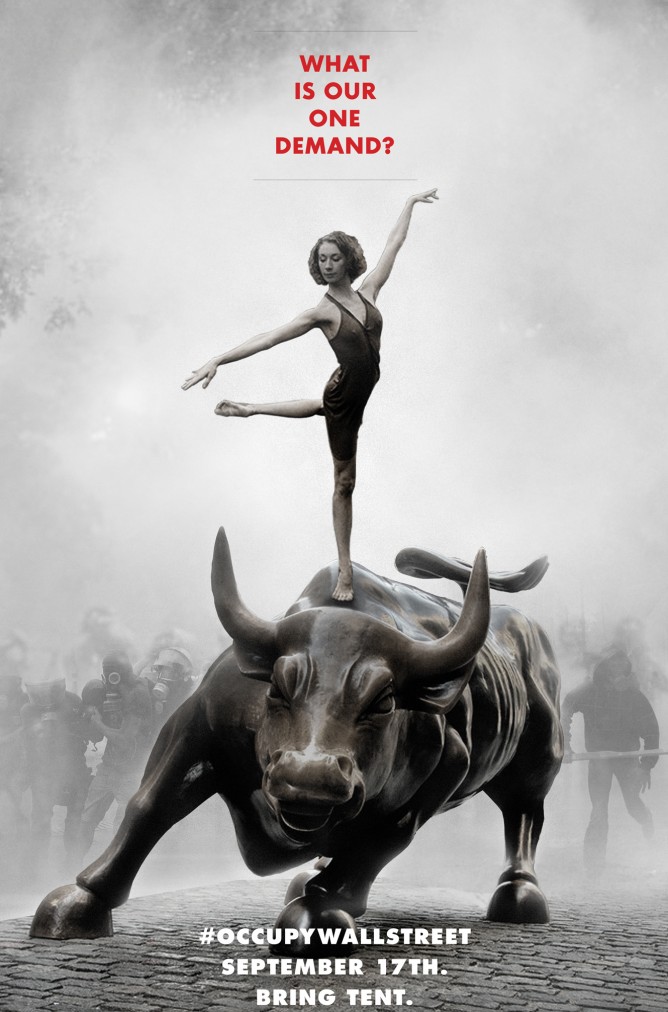

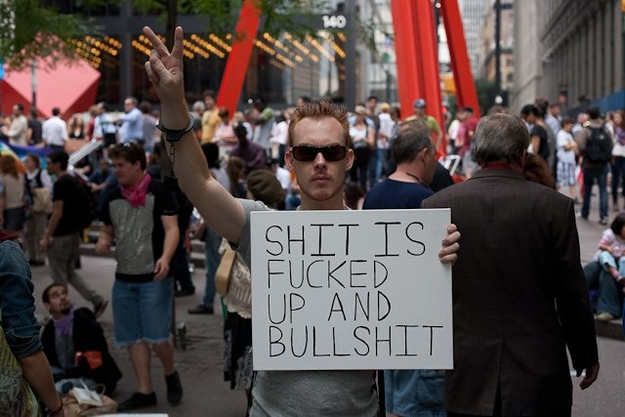

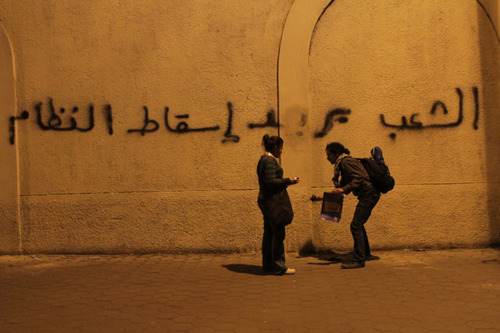

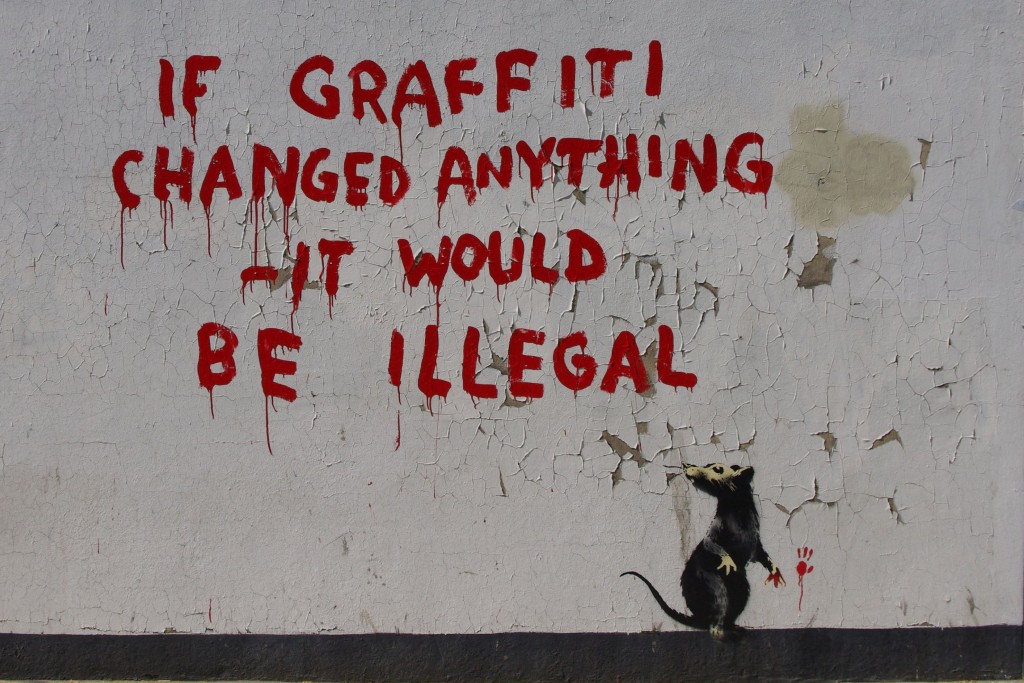

They are in New York on Thursday, hosted by the fab Interference Archive. EDLMR produce conventional art work like these posters:

While those of a certain age will recognize the graphics of 1968 here, that was nearly fifty years ago. They are new to many younger people and in any event continue to have a striking visual and political impact.

EDLMR have also created Red Squared, an online project.

The site has everything from film to graphics, documentation of demonstrations, music and art. Check this out for example. Be sure to find the project on The Social Contract.

The event is hosted by the Interference Archive, whose importance is described by Cindy Milstein:

If we’re committed to making a better future, that also means saving, remembering, and scrutinizing our past (and present-day) struggles to get there, and doing so outside those hierarchical and privatized institutions that either don’t want us to remember — because that can be mighty subversive — or only allow certain privileged individuals access to that knowledge.

No new archives, no new learning. In an era obsessively dominated with memorials to trauma, how great to have an archive of the àvenir. Interference Archive works with OWS and Quebec. By the way, they could use some help.

Today, the next iteration of the fab Free University of New York City was also announced. The first major event was on May Day in Madison Square Park and there have been meetings throughout the summer, intertwined with All In The Red and other solidarity actions for Montréal. Now the Free U is calling for a full week of actions from September 18-22, following S17. You can propose an idea, or help or both. Do it.

The future is now, now is the future, it is come, it is to come.