What would we have to reconstruct after abolition? How might we think about the relations between the gender and sexuality expressed in finance with the exploration of new forms of living? The abolition of debt and the refusal of heroes was and is mediated by land. Land is a way to think our relation to the biosphere extinction. It’s at the root of the ongoing disaster of personal debt via mortgages (details tomorrow), just as it was key to the possibility of a post-slavery Reconstruction.

I can’t as yet make this all come out neatly. But here are the things circulating in my mind. The 1868 Constitutional Convention in South Carolina was pre-occupied with debt and identity. A proposal was made to ban the words “negro, nigger and Yankee” but it was voted down at once. There was a debate whether to outlaw discrimination by “race or color.” Many of the freed wanted to keep the word “color” out of the new Constitution. Others feared that without an explicit ban, Democrats would find a way to divide people by “race,” as indeed they did. Very late in the Convention there was an unsuccessful proposal to enfranchise women, who did so much of the work of abolition and reconstruction.

The true division of the sensible that was the ongoing class war in South Carolina in 1868, as it had been since 1863, was over land. The freed wanted above all to have some land, as means to form autonomous communities. They saw that the altermative was poverty and/or the penitentiary, as Angela Davis has so often reminded us.

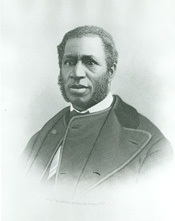

The minister Richard Harvey Cain, who later served two terms in Congress as a Republican, proposed a solution: the Convention would apply to Congress for a $1 million loan in order to buy land for re-sale to the freed and poor whites. The ensuing debate was the nastiest of the Convention and made it clear to the African American delegates that the Confederates still believed that a “negro would never own a foot of land” in the state.

In the Convention, Cain put his proposal to sell plots of land over a five-year period like this:

We want these large tracts of land cut up…What we need is a system of small farms…I believe there are hundreds of persons in the jail and penitentiary cracking rock today who have all the instincts of honesty, and who, has they the opportunity of making a living would never have been found in such a place.

Reconstruction was made to fail by means of the emergent prison-industrial complex, from the determination of planters to offer only starvation wages to make share-cropping seem preferable to the use of all state apparatus to confound efforts to buy land.

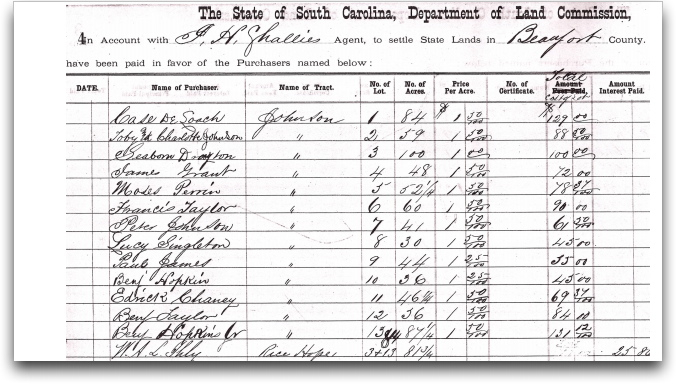

The resolution to request a loan from the Bureau of Freedmen passed but was ignored in Washington. In 1869, the state established its own Land Commission to buy and resell land. The freed made all efforts they could.

You can see here that the land was selling for $1.50 an acre, compared to the planters’ (starvation) wages of $5 a month. A woman called Lucy Singleton bought a 30 acre plot, as did Charlotte Johnson with her spouse or relative Toby. For the most part, these ventures did not end well. The repayments proved beyond them, as the Wall Street crash of 1873 depressed prices for all produce. The very short repayment window was not a great idea.

Some did succeed. Cain himself established a settlement called Lincolnville with six others, which they selected because it was next to the railroad tracks. The town is still there today. Others survived in what had long been liminal spaces on the coast. If you’re of a certain age you might remember the intersection of Carrie Mae Weems and Julie Dash’s work on the Sea Islands twenty years ago.

This was the first time I had heard of the self-killing of the enslaved–it happened often in fact, because in their world-view death would later be followed a re-birth in Africa.

Her photograph of the site of Ibo Landing had no caption. It still gives me the creeps today. Released at the same time, Julie Dash’s now classic film Daughters of the Dust (1991) visualized the hyperlinked time of Reconstruction between past and present. Set in 1902, the film shimmies between African pasts and futures in the Sea Islands. Dash explicitly wanted her viewers to think about the beginning and end(s) of the twentieth century, a task that we perhaps have to revive for the new century that is upon us.

None of this provides a simple set of “to do” items that will resolve these interfaces of the economic, with identity, history and temporalities. I would say, though, that those interfaces are exactly what I have taken Occupy to be. It’s not of course that Reconstruction alone pre-figures Occupy. But once you think of a lineage that includes Du Bois, Angela Davis, feminist and African American arts and culture, alternative economics and food provision, you do have something you can work with.