Axiomatic: to occupy is to place your body in space, there where it is not supposed to be. That space is three-dimensional but multiply so. Some of these can be evicted, some not. Some are not visible to the empire. But we can see it because power visualizes what it imagines history to be to itself. Let’s look around.

In the first instance, Occupy takes physical three-dimensional space in urban environments. It is attention-generating because the populace in global cities are highly regulated and policed. “Public” space is subject to particularly dense control, meaning that (in the U. S.) public-private spaces, where guaranteed access was the definition of “public,” became the location of choice.

To occupy global city space is also to intervene in the highly-mediated imaginary of “New York.” Citizen and professional media alike are so densely configured and adept that actions taken by a relatively small number of people receive immensely multiplied levels of attention. Thus it seemed obvious to state power that removing those bodies from their spaces would end Occupy.

There are multiple spaces available, however, in vertical and horizontal configurations. Conceptually, the horizontalidad of direct democracy is challenged and displaced by the verticality of power and neo-liberalism: and vice-versa. In their trilogy on Empire, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri give some useful ways of thinking about this encounter. Borrowing from the ancient historian Polybius, they suggest that the global empire can be understood as a pyramid with three levels: monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. The monarch would be the United States, the aristocracy would be the agents of globalized economics, and democracy is associated with what they call the multitude.

Bringing this figure up to date, they adopt the image of the mainstream foreign affairs commentator Joseph Nye, who suggests:

The agenda of world politics has become like a three-dimensional chess game, in which one can win only by playing vertically as well as horizontally.

His aim was to correct the Washington-speak idea of a “uni-polar” world governed by the US, and replace it with three “boards” representing “classical military interstate issues,” or war. This was placed above the level of “interstate economic issues,” meaning the global economy. Finally the whole rests on a base of “transnational issues, [where] power is widely distributed and chaotically organized among state and non-state actors.” In some ways, Nye has less respect for the level of the multitude than Polybius but he does realize that power cannot be exercised without its at least passive consent.

Let’s push this a bit harder. The game of Raumschach, literally “space chess” or three-dimensional chess, was devised in 1908 by Ferdinand Maack in Hamburg. He felt that as chess was a war game, it should now be possible to represent aerial and submarine warfare as part of play. His initial concept was for an 8x8x8 board that looked like this:

8x8x8 "space chess" in 1908

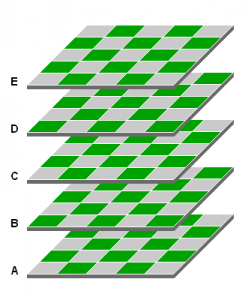

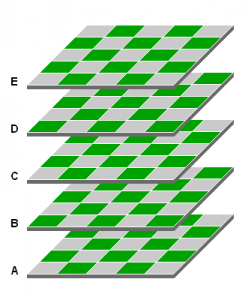

He refined this towering edifice to 5x5x5, the variant now mostly used by the devotees of the game. Pieces can move in three-dimensions: a rook, for example could move from top to bottom vertically, while a knight could move two layers up and a square across. Players use the standard pieces, plus two “unicorns” that can move from corner to corner. The board looks like this:

Raumschach 5x5x5

In short, let’s by all means think of the political as a three-dimensional contest but be aware that it would have more than three layers and the possibilities for interaction are very diverse. Occupy geeks of a certain kind will already have this in mind:

Spock plays 3-D chess against the computer in Star Trek

The future used to be imagined as a liberatory expansion into space of all kinds. If in Star Trek, this expansion was hard to separate from the colonial and Cold War projects of the U. S., the fans were always able to imagine otherwise in slash fiction and other forms.

However, let’s follow Nye this far: the “top board” of global conflict is the one now in chaos. The counterinsurgency doctrine launched with such fanfare in 2006 stands revealed in Afghanistan as the imperialist fantasy it always was–such is 3-D chess, a game of imperial imagination. But with the “monarch” having lost control of the top, the game is now open in a variety of ways.

Vertical power is not just exercised by states or interstate organizations. In contrast to their usual emphasis on immaterial labor, Hardt and Negri point out that

Extraction processes–oil, gas, and minerals–are the paradigmatic industries of neoliberalism.

This “verticality” of this economic power is literal as well as metaphorical: the rewards for mining fossil fuels and other raw materials are spectacular. The sea level rise that results from the resulting acceleration of climate change is by the same token a literal and metaphorical verticality: only those in the “high places,” like the Tyrel Corporation in Bladerunner, can and should survive.

The primary alternative available form of wealth increase in overdeveloped nations at present is privatization and upwards wealth distribution by means of regressive taxation and other measures. In short, the verticalization of what had been made horizontal by political action, such as the former attaining of free university education that is now a market for private loans.

These are nonetheless relatively crass and unsubtle ways to play. If you have sufficient pieces, they may gain an advantage, perhaps some victories. But there are at least two, perhaps five, perhaps many more levels at which our would-be hegemons are not playing because they can’t see them.

Take the horizontalism of direct democracy. In this exchange, each person consents to look and be seen at once. To authority, this exchange is invisible. Formally, authority imagines itself as deploying the gaze with its force of law in which we are the looked-at, the passive object. In this view, direct democracy is just chaos.

By the same token, as I argued yesterday, there are always already spaces of the “primitive” where power is not vertical, disrupting the arrangement of the “boards.” Such spaces are equally invisible to authority because they are not part of its life processes but they are nonetheless present, understood as ghosts, spirits and specters. Indeed, there are places that, in the manner of China Miéville, we might call crosshatched with other pasts, futures and presents, intermittently visible.

On these horizontal levels, you can win the game by playing only horizontally, or by cancelling certain vectors of the vertical by using your “unicorns.” If the unicorn does not “exist,” that speaks to the ways in which magic–understood here as that which exceeds the “rational actor” theory of value–continues to be a real presence. Colonial power always feared the magic of local religions because it knew that it “worked,” meaning that it generated horizontal values and imaginaries, as well as moves to negate the vertical.

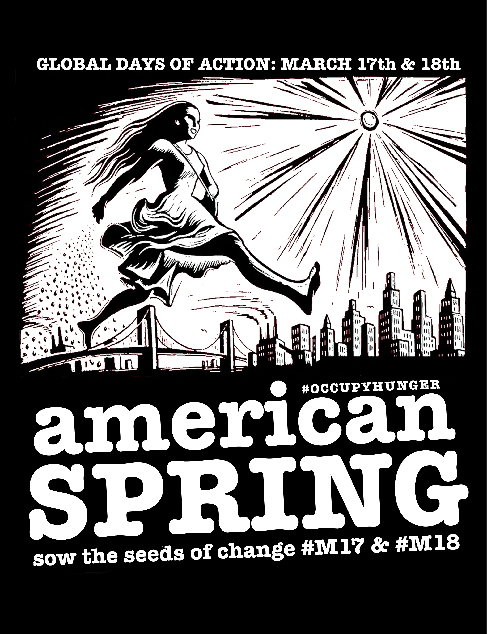

That’s why the signs saying “Game Over” in Egypt seemed so right. But this an odd game. You can checkmate the king only to find, like in the horror movie, that it is back in mutant form. The same is true for both sides. If empire has more power, its narrowness of vision means that Occupy has, paradoxically, more space. Game on.

Like this:

Like Loading...

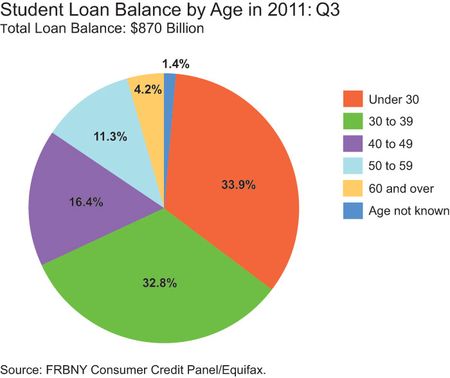

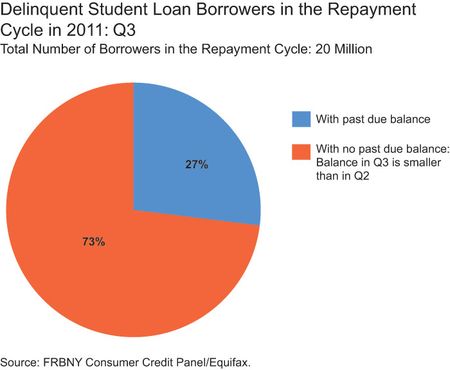

The new refusal of the student debt crisis first evidenced by the Occupy Student Debt Campaign appears to be spreading and to have good cause. Student strikes are shutting down Montréal, while new evidence makes it clear how serious the crisis is now and how it is going to get worse soon.

The new refusal of the student debt crisis first evidenced by the Occupy Student Debt Campaign appears to be spreading and to have good cause. Student strikes are shutting down Montréal, while new evidence makes it clear how serious the crisis is now and how it is going to get worse soon. That percentage is set to increase still further. The Obama administration has changed the regulations so that new federally subsidized graduate student loans will incur interest while a student is still in school as of July 1, 2012. As those loans currently attract 6.8% interest, a student in school for the six to nine years it takes to acquire a doctorate would find their loans had ballooned before they had even graduated.

That percentage is set to increase still further. The Obama administration has changed the regulations so that new federally subsidized graduate student loans will incur interest while a student is still in school as of July 1, 2012. As those loans currently attract 6.8% interest, a student in school for the six to nine years it takes to acquire a doctorate would find their loans had ballooned before they had even graduated.