Today the Greek parliament met to approve the deliberately humiliating terms of the German-backed bond rescue plan (aka the bailout). In the streets, it is more precisely defined as slavery. The response is, as it has long been, to organize the general strike. For globalized neo-liberalism this is the moment to bring an “end” to 2011, a year after their man in Egypt, Mubarak, had to step down.

Estimates suggest 50,000 people in the street in Athens, perhaps as many as 100,000 with thousands more elsewhere, and many buildings occupied. The inevitable riot police and tear gas have been deployed. Exarchia, the radical district resounded to explosions. As fires burned, allegations circulated that the police had started them or ignored them. (Watch on Livestream here.)

The scenes were extraordinary–Starbucks on fire, smoke bombs, riot police–with the word “chaos” on every Greek website.

The troika-installed Prime Minister Papademos–whose name seems to evoke a patriarchal “father of the people”–pushed the market line about debt refusal:

It would create conditions of uncontrolled economic chaos and social explosion. The country would be drawn into a vortex of recession, instability, unemployment and protracted misery.

Such remarks fly in the face of existing reality, in which those are already the prevailing conditions. Official unemployment exceeds 20%. Reports have suggested people returning to family farms in the countryside and islands from the cities in order to survive. The Church feeds 250,000 people a day in a country of 11 million people. Homelessness has increased by 25% (although the absolute numbers are low by U. S. standards. The official EU statistics agency Eurostat reports that one-third of the country is living in poverty. And yet Papademos called for more “sacrifice.”

Nonetheless, even this is not enough for the one percent: “The promises from Greece aren’t enough for us any more,” the German finance minister, Wolfgang Schauble, said in an interview published in the Welt am Sonntag newspaper. When the vote is passed, the minimum wage will be cut by over 20%, pensions will be reduced and the already ruined state will cut back still further. The graffiti in the streets calls this slavery.

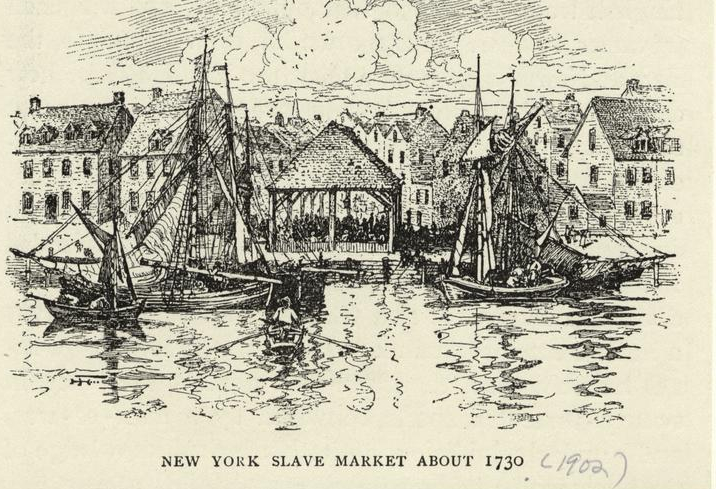

“We should not live as slaves,” it reads [Na men zesoume san douloi]. Evocatively, the word “doulos” is used for “slave,” the same term used by Aristotle in his Politics to approve the institution of slavery. His meditation on slavery is in fact one of governance, which manifests itself as the necessity of dominance. I’m going to quote at some length because it is the inability to “reason” according the “logic” of the markets that is being used to justify Greek slavery today. It’s also important to read this to realize how thoroughgoing and long-lasting the Western commitment to slavery has been.It is also a passage that contains within it so many of today’s critical concerns from the human/nonhuman, to the “soul at work” (Bifo), governmentality, Rancière’s division of the sensible, and the persistence of slavery. Let us note this is not a coincidence:

for that some should govern, and others be governed, is not only necessary but useful, and from the hour of their birth some are marked out for those purposes, and others for the other, and there are many species of both sorts….Those men therefore who are as much inferior to others as the body is to the soul, are to be thus disposed of, as the proper use of them is their bodies, in which their excellence consists; … they are slaves by nature, and it is advantageous to them to be always under government. He then is by nature formed a slave who is qualified to become the chattel of another person, and on that account is so, and who has just reason enough to know that there is such a faculty, without being indued with the use of it; for other animals have no perception of reason, but are entirely guided by appetite, and indeed they vary very little in their use from each other; for the advantage which we receive, both from slaves and tame animals, arises from their bodily strength administering to our necessities; for it is the intention of nature to make the bodies of slaves and freemen different from each other {1254b-1255a}

The present rhetoric of the “lazy” Greeks, shiftlessly avoiding tax payments and demanding state support defines people driven entirely by appetite. They must therefore become the chattel of the troika, despite the likelihood that the cuts will still worsen the economy and necessitate yet more support for the external bond markets. What matters is that the Greeks be made an example: “Can’t pay! Won’t pay!” is reworked into “Can’t pay? Become a slave.”

In Black Reconstruction, W. E. B. Du Bois insisted that the enslaved had ended chattel slavery themselves by mass migration from South to North at the beginning of the Civil War, long before the Emancipation Proclamation:

This was not merely the desire to stop work. It was a strike on a wide basis against the conditions of work. It was a general strike that involved directly in the end perhaps half a million people.

The result of the strike was an abolition democracy, whose participatory process centered on education and the capacity to be self-sustaining. The measures have passed. The occupations have been ended. It’s up to us to keep this present, to remain in the moment, to be present.