For the history of the anonymous to be written, it must first be visualized as something other than an absence. Since Mrs. Thatcher famously declared “there is no alternative” in 1980, neo-liberalism has been devoted to making this task impossible. Such a visualization is neither a history from below or a particular set of images but a reconfiguration of the “cognitive mapping” of the social. More precisely, it is the possibility of such a mapping, the ground against which it would be made and the techniques to be used in its formulation. A year ago this week that process began with the revolution in Tunisia.

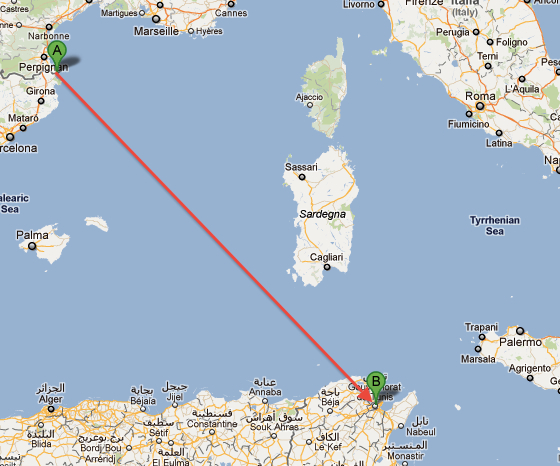

On a climate-changing rainy day last August, I stood on a Spanish clifftop by the “Passages” memorial to Walter Benjamin, outside the cemetery where he was buried in 1940. It was not far to Barcelona with its neighborhood assemblies and a half-day on the train to Madrid and the indignados. But from the cliffs, you look out to sea, southwest, towards Tunisia, where a fruit-seller named Mohammed Bouazizi immolated himself into history as the person in whose name the Tunisian revolution of 2011 was enacted a year ago this week. The force of that revolution changed the way that I understood the monument.

Designed by Israeli artist Dani Karavan and opened in 1994, “Passages” encloses a flight of stone steps running down towards the sea in a rectangular iron frame that encloses the entrance but opens up further down. Towards the bottom, there is a sheet of glass engraved with a shortened version of Benjamin’s aphorism from On the Concept of History (1940):

It is more difficult to honor the memory of the anonymous than it is to honor the memory of the famous, the celebrated, not excluding poets and thinkers. The historical construction is dedicated to the memory of the anonymous.

The construction of the iron sleeve acts as a projector so that the visitor also sees his or her own image projected, as it were, onto the open sea.

In order to visualize a history of the anonymous, then, one has to superimpose Benjamin’s aphoristic writing on this phantasmatic projection of the self. The result of the contact between these layers is the new historical construction.

For a long time, it was hard to see oneself against the imagined background of European fascism, the imperative to never forget overwriting all other presents and futures, turning the projection into a spectre, erased on the always moving waters below. Michael Taussig’s fine essay on the memorial is haunted in this way, overwritten with the memory of 9-11. Like the photograph, always already about death as the Barthes-Sontag tradition has it, the memorial is held to be memento mori. Such is the posture of the angel of history, condemned to look back at the past.

History itself, Benjamin liked to remind us, is Janus-faced: it looks both ways. So if there are the anonymous of the past to be remembered, there are also the anonymous of the present to be named, projected by the very memorial itself into a different history than the history of great men. This transitory seawriting is not so much photography as photograffiti, a writing of the self by light that claims the privilege accorded to the name.

In his last preserved writing in 1940, Benjamin noted that in order to preserve the memory of the anonymous, it was necessary that “the epic moment will always be blown apart.” The epic is the account of gods and great men, once memorialized in portraits, now depicted in the ceremonial photograph such as that of Ben Ali, the only portrait photograph seen in public in Tunisia for the past forty years.

Blown apart, which is not the same as blown up in either the photographic or military sense, photograffiti allows for a photographic common that turns hierarchy inside out and visualizes the present as prologue to a differently visualized future, rather than as the repetition of the past.

[part one of a series: this was originally given as a talk called ‘Occupy Visuality.’ It’s gradually evolving into an essay for a collection called ‘After the Global Turn’ edited by Aruna da Souza and Jill Casid.]