The new report on debt from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York presents the case for a decline in household debt. Which is true, if you exclude bankruptcy, foreclosure, and student debt all of which are up. And forget trying to get a new mortgage at those nice low rates you hear about: the banks aren’t lending at all. What we’ve got here is a privatized austerity that’s affecting individual lives every bit as much as its nation-state implemented partner in Europe. In this privatized form, debt-driven austerity presents less of a political target. Silence=Debt. Which is why we strike debt.

Let’s look at the Fed’s own numbers. With student loans, the news is all bad, explaining in part why, of all debt topics, attention continues to be centered on student loans:

• Outstanding educational debt stood at $914 billion as of June 30, 2012 [previous Fed figures had it at $870 bn]

• Since the peak in household debt in 2008Q3, student loan debt has increased by $303 billion, while other forms of debt fell a combined $1.6 trillion.

• Student loan delinquency rates increased for the second consecutive quarter; The percent of student loan balances 90 or more days delinquent increased to 8.9% from 8.7% during the second quarter of 2012.

Note that the delinquency rate here is across all student loans, including those currently in deferral. The Fed itself has reported that 27% of loans not in deferral are in some stage of default. The increase in student debt is a direct consequence of the impossibility of declaring bankruptcy or defaulting on these loans.

So we need to be careful about the assumption that the numerical decline in bank reported debt means that people’s situations are improving. To the contrary, as bankruptcy and default increase, banks move debt off their balance sheets, making their situation appear better. For the debtor, the situation is in fact worse.

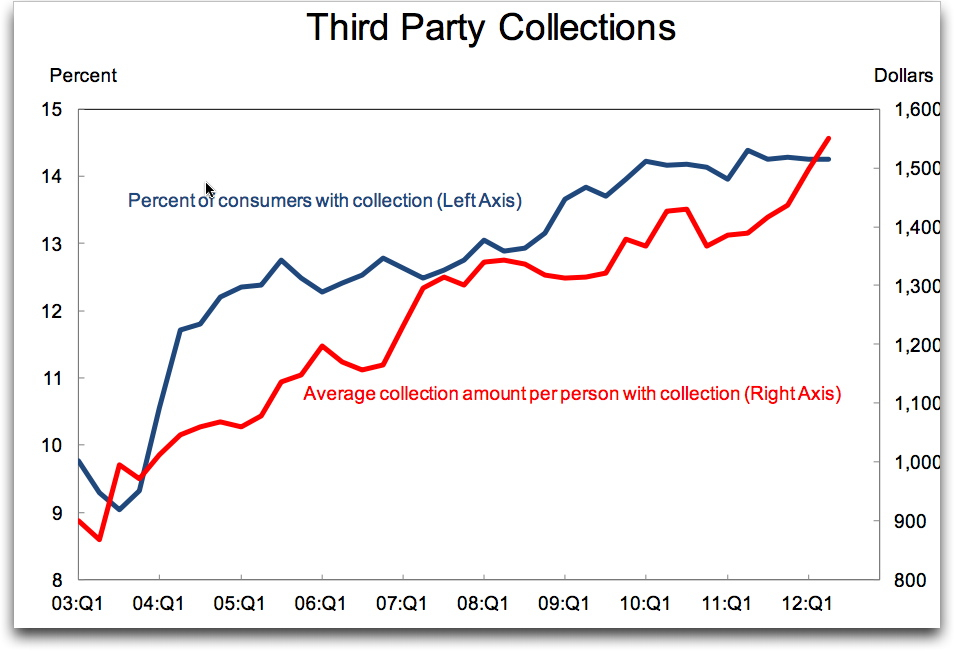

Here we can see that more people are being pursued by debt collectors for larger sums than ever:

This chart suggests that about 14% of consumers are in collection and the amounts are climbing steeply to an average of $1550.

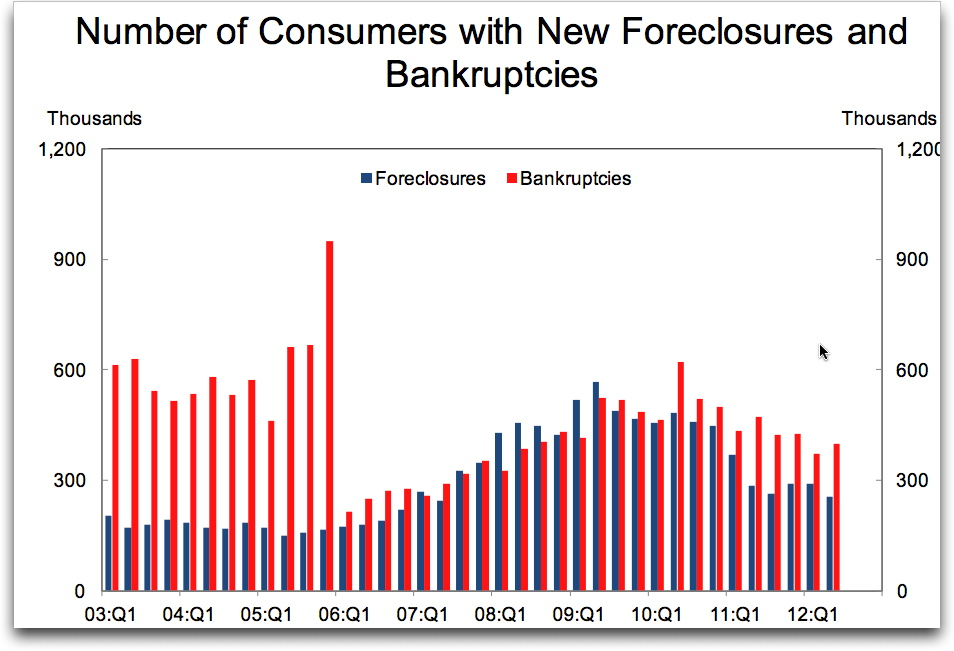

As we might expect from this, bankruptcies are up, while foreclosures are running back at 2011 rates, despite the 5 million people who have already lost their homes

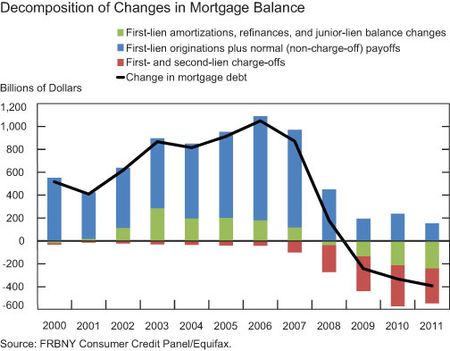

So how can total household debt be lower? Here’s the giveaway detail. Foreclosures and bankruptcies allow banks to remove that debt from their balance sheets. The people concerned are now invisible, statistically unaccountable and therefore (it is hoped), politically neutralized. Here’s the Fed’s visualization of that for mortages:

The red section of the bars refers to “charge-offs” meaning defaulted or foreclosed loans. The more these increase, the lower total mortgage debt becomes as you can see here, as represented by the black line.

Notice also that the blue bars depict new loans and mortgages that are actually paid off by the homeowners. This number has now declined to irrelevance. If we assume that some folks are in the course of time managing to pay off their 30-year loans, then the amount of new mortgage lending is very low indeed. That would accord with the anecdotal sense that, despite notionally low interest rates, mortgages are now impossible to get. The federal funds set aside to help underwater mortgage-holders have been little used, not because people don’t want them, but because banks put so many obstacles in the way of refinancing.

Unlike European austerity that is visibly punishing the 99% to recoup the excesses of the one per cent, this silent austerity has come with relatively little political consequence. A Wall Streeter whose entire enterprise rests on forcing companies into debt and then cashing out, leaving them to pay off the debt, is at 50% for the presidency. He’s only doing to companies what the banks are doing to all of us.

Strike back. Strike Debt Assembly at 1.30, followed by Life After Debt: A Gathering of Debt Refusal at 4pm, this Sunday in East River State Park in Williamsburg.