From Tidal for S17 by Strike Debt:

STRIKE DEBT/DEBT STRIKE/DEBT

WHEN WE STRIKE DEBT. WHY WE DEBT STRIKE. HOW TO MAKE DEBT:

We must remake our failed economic system that impoverishes millions while destroying the ecosystem. Using a diversity of tactics that includes a Rolling Jubilee, a People’s Bailout, and vigorous organizing towards a debt strike, Strike Debt seeks to abolish debt and reconstruct a just society where our debts and bonds are to one another and not the 1%.

When you strike debt, know that:

1. You are not a loan.

Debt is not personal, it is political. The debt system molds us as isolated, scared and subjugated, unwilling to consider going public for fear of the all-powerful credit ratings. There is a reason so many people speak of debt as slavery. Slavery was social death. So is debt. It makes us ashamed. We have to sell our time, our souls, working jobs we don’t care about simply so we can pay interest to the bank. Now that debt is so rampant, many of us are ashamed for putting others in debt. Our professions from teacher to lawyer and physician have become means to direct more victims to the loan sharks. So perhaps above all, we strike the fear, refuse the shame, end the isolation. When we strike debt, we are giving ourselves permission to be more than a set of numbers. In a sense, we create the possibility of an imagination. We are not abdicating our responsibility, we are exercising our innate right to refuse the unjust.

2. We live in a debt society, buttressed and secured by the debt-prison system.

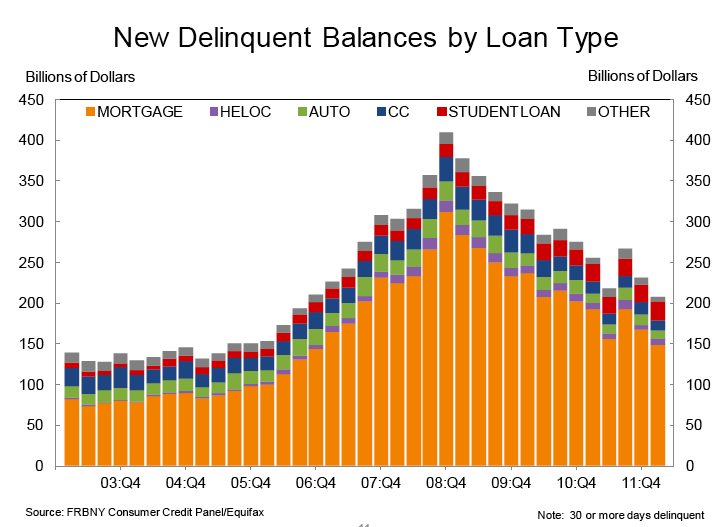

$1 trillion of student debt. 64% of all bankruptcies caused by medical debt. 5 million homes foreclosed already, another 5 million in default or foreclosure. Credit card debt is $800 billion, generating an average 16.24% interest on money banks borrow at 3.25%. Permanent indebtedness is the pre-eminent characteristic of modern American life. Keeping all this in check is the peculiarly U.S.- specific apparatus, in which mass incarceration, racialized segregation and debt servitude are mutually reinforcing. The choice is stark: debt or jail. With 2 million in prison, seven million involved in the “correctional” system in various ways and sub-prime loans and other predatory credit schemes targeted at people of color, this is a system designed to disenfranchise and exclude.

3. There’s A Debt Strike Going On

There is something happening in our debt society right now. 27% of student loans are in default. 10% of credit card debt has been written off as irrecoverable. Foreclosures and mortgage default are rampant. People are walking away from debt. These actions take place driven by necessity, by desperation but also by something else. What do we call this? We could call it refusal. We could also call it a debt strike. In this time of high unemployment, battered trade unions, and job insecurity, we may not be able to signal our discontent by not going to work, but we can refuse to pay. Alongside the labor movement, a debtors movement. For those who can’t strike, we propose a Rolling Jubilee in which we buy debt in default, widely resold online for pennies on the dollar: and then abolish it. It will be funded by the People’s Bailout, and other forms of mutual aid that will prefigure alternatives to the debt society.

4. When we strike debt, we live a life rather than repay a loan.

We refuse to mortgage our lives. We reject the math that debt forces on us; math that says we cannot “afford” to care for our communities because we must “pay back” the banks forever, above and beyond what was borrowed. We question the dominance of the market in every aspect of social and cultural life. We abolish the trajectory of a life that begins with the assumption of debt before birth, and ends with a post-mortem settlement of accounts. This is financial terrorism. We intend to reconstruct a social world in which we see each other as people, recognize our differences, and acknowledge that the chimera of permanent economic growth cannot outstrip actual ecological resources.

5. We claim the necessity of debt abolition and reconstruction.

Abolishing debt is held to be an impossible demand. “Debt must be repaid!” Unless you are a corporation, bank, financial services company, or sovereign nation. We understand that debt is at the heart of financial capitalism and that the system is rigged to benefit those at the top. The question is not whether debt will be abolished but what debt will be abolished. The banks, the nation-states and the multinationals have seen their debts “restructured,” meaning paid off by the people, who now have to keep paying more. The debts of the people in whose name these actions were undertaken should also be abolished. Then we can begin reconstruction, transforming the circumstances that create the destructive spiral of permanent personal debt. Right now we must borrow to secure basic goods that should be provided for all: housing, education, health care, and security in old age. Meanwhile, around the world, debt is used to justify the cutting of these very services. We understand that government debt is nothing like personal debt. The problem is not that our cities and countries are broke but that public wealth is being hoarded. We need a new social contract that puts of public wealth to equitable use and enshrines the right to live based around mutual aid, not structured around lifelong personal debt.