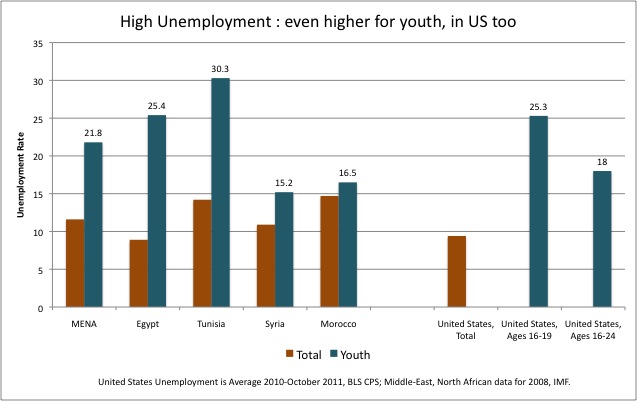

The subprime Depression of 2008 to the present has entailed a notable wave of personal depression. At the same time, neoliberal austerity presents itself as a required correction from the superego for the excessive “exuberance,” as Alan Greenspan notoriously called it, of the boom. Yet the formerly exuberant are not the depressed: we are. Depressed about debt, climate change, unemployment, you name it. All efforts to mobilize a political response, even the irreversible step of self-killing, have to be discredited in order to maintain the regime of credit. It is in every sense unsustainable.

These thoughts were prompted by the observation that the suicide of a 77-year-old man in Syntagma Square on April 4 has now provoked a wave of mitigating journalism. Feeling unable to survive on his austerity-reduced pension, Dimitris Christoulas left a suicide note that was a call to action (I don’t wish to edit this, so the quote is long):

The Tsolakoglou [1940s Nazi-collaborationist] occupation government literally nullified my ability to survive on a decent pension, for which I had already paid (without government aid) for 35 years. I am of an age that prevents me from offering a decent individual response (without of course ruling out the possibility of being the second person to take arms, should one person decide to do so), I find no solution other than a dignified end, before resorting to going through garbage in order to cover my nutritional needs. One day, I believe, the youth with no future will take up arms and hang the national traitors at Syntagma Square, just like the Italians did with Mussolini in 1945 [at Milan’s Piazzale Loreto[.

Not unlike Stéphane Hessel, the former French Resistance activist turned writer, Christoulas saw a parallel between the fascist occupation of Greece in the 1940s and the current decimation of social life by the Troika.

In the days following, pieces from Ireland to Italy, Jakarta and now New York have created a new syntagm “suicide by economic crisis,” traveling from newspaper to newspaper. The verb-less fragment gives agency to the economic crisis as the means of self-killing, just as one might say “suicide by hanging.” In today’s New York Times piece, Christoulas is neither named nor quoted. Instead, the lead goes to a debt-destroyed Italian contractor named Giovanni Schiavon with a more familiar message

Sorry, I cannot take it any more.

This “acceptable” message (for those not acquainted or related to the self-killer) is the regime of truth around depression, bipolar conditions and self-killing: it is an individual “tragedy,” which could and should be prevented by medication.

Yet the self-killing to provoke social change has a long history. It was a resistance to empire, as in the suicides of the enslaved, and also its tool in episodes like the suicidal attacks of the First World War. Recently it has been the weapon of asymmetric warfare, most notably on 9-11, and the last resort of the oppressed, such as the self-immolation of Mohammed Bou’azizi in Tunisia in December 2010. Christoulas was clearly hoping to provide a similar inspiration to that of Bou’azizi and it remains to be seen what may yet happen in Greece.

Earlier in this project, I thought about Antigone as a figure for resistance. She might be said to have suicided by state, in the same way that people today are said to choose “suicide by cop” when they get shot by the police. For she knew that to bury her brother was to incur death at the hands of Creon, and she welcomes it as a path to what she calls “glory” in Sophocles’ play.

In Judith Butler’s telling analysis, Antigone’s story reveals that the carefully policed distinction between the social and the symbolic cannot hold. In the present crisis, it is notable how Antigone welcomes the grave as a “deep-dug home to be guarded forever,” as if suiciding wards off symbolic and social foreclosure. Butler concludes that what Antigone

draws into crisis is the very representative function itself, the very horizon of intelligibility.

Butler notes that those who disagree that the “law” (here as much the psychoanalytic law of the Oedipus complex as state law) must hold accuse her of “radical anarchy.”

Perhaps it’s time to embrace that anarchy rather than foreclose it. Perhaps the crisis of the representative engenders a new horizon-tal, making intelligible what it would be to live in a sustainable social world of degrowth and chosen kinship. For Antigone’s choice puts pressure on all norms of gender, as she challenges the “manly” place of sovereignty. It is telling that all the people said to be affected by debt and depression in this recent flood of articles are men. It seems that the old binary that men work, while women care is still in circulation.

I do not wish to minimize the actual experience of depression and its cognate diseases. Each year there are said to be 30,000 suicides by bi-polar people in the US and an estimated one million attempts. For Franco “Bifo” Bifardi and others in the radical psychiatry movement known as “schizoanalysis,” these conditions are not random but actively produced by a regime that insists on the pure rationality of a market that is nonetheless out of control. Bifo sees a “bipolar economy” that insists on more and more stimulus, leading to the inevitable crash. Even the Harvard Business Review now accepts that there is no “invisible hand” guiding the market, which does not attain the mythical “general equilibrium.” Now it’s generally on Lithium.

What would be the resolution for those so depressed today? It would be literally to get outside, outside the depression but also into different spaces, as Félix Guattari puts it

to get out of their repetitive impasses and in a certain way to resingularize themselves.

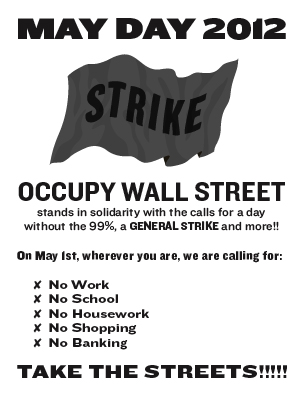

As I said on Friday, being at Occupy makes me less depressed. I am certainly aware that the kind of unmet need that the Occupy encampments did much to reveal is not going to dealt with so easily. However, the statistics on suicide make it just as clear that the psycho-pharmaceutical regime isn’t working any better. The desire not “to be a statistic,” as the euphemism for suicide goes, is suggestive. It expresses a hope for the resingularizing of people as non-normatized individuals with a right to the pursuit of happiness that is not measured in consumption patterns.