One of the most resistant spaces to the global Occupy movement is the global imaginary, by which I mean the way in which we imagine the planet. While the push-back against financial inequality has been very successful, with the 99% vs. one per cent divide now part of the global political vocabulary, we have not succeeded in framing an alternative means of visualizing the planet. That space remains occupied by the Cold War imaginary of binary divides between hostile camps, all underpinned by the threat of nuclear war.

What sets the Occupy way of visualizing against neoliberal financial globalization is its willingness to bring issues together, to embrace complexity and to see patterns of relation. Yet in the case of the largest system of all, Earth, we have failed to shift attention towards the reckless destruction of liveable space in the name of profit. Strikingly, any effort to discuss the degradation of the Earth-system is designated even by radicals as a depressing subject–this from people who love nothing more than to read long essays describing how capitalism is collapsing, poverty increasing, employment disappearing.

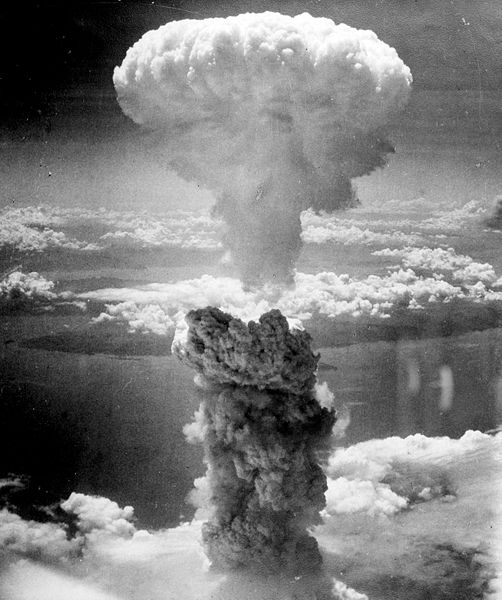

So it’s not the depressing nature of the subject as such. It’s the sense that this subject is itself, as it were, futile because the imagined destruction of the planet is already occupied by nuclear weapons and the world they have produced. In this view, the military are the indispensable key to continued safety and it has been an article of neoliberal faith to maintain massive military budgets, while cutting all other areas of government. Thus we imagine we are “safe.” We have to expose this old idea for the peculiar hodgepodge of 1950s militarism and 1980s economics that it is, while espousing the new synthesis of science, anti-poverty, pro-diversity that has emerged in the past decade as a path to a real security that does not depend on world-ending weapons.

The Cold War spectres continue to haunt the earth. Consider how Romney has cited Russia as the greatest enemy of the U. S. More saliently, reflect how overwhelming the transnational governing consensus that Iran must not be “allowed” to acquire nuclear weapons has remained. This is old-fashioned Cold War doctrine: nuclear proliferation is bad, not because nuclear weapons are bad, but because it undermines the deterrence of the superpowers. In short, if “small” nuclear powers might actually use their weapons, then the deterrence of massive arsenals counts for nothing. How that works in the post-Soviet era no one seems to have tried to work out.

The evocation of the nuclear activates a form of pre-emptive dread, in which many of us have literally been schooled. It has been visualized many times but perhaps the 1964 “Daisy” ad for President Johnson did it best.

“Daisy” reminds us of “s/he loves me, s/he loves me not” and all the other binary games that you can play like this. The choice here is simple: to die or not to die. The ad mobilizes a fantasy that by voting we can affect our own destiny in the geopolitics of nuclear weapons. For many, the current crisis in the Earth-system lacks such a vision of solution and so it’s “depressing.” Now the International Council for Science has issued a “State of the Planet Declaration” that allows for us to imagine a different geo-politics. Here are its opening three clauses:

1. Research now demonstrates that the continued functioning of the Earth system as it has supported the well-being of human civilization in recent centuries is at risk. Without urgent action, we could face threats to water, food, biodiversity and other critical resources: these threats risk intensifying economic, ecological and social crises…

2. In one lifetime our increasingly interconnected and interdependent economic, social, cultural and political systems have come to place pressures on the environment that may cause fundamental changes in the Earth system and move us beyond safe natural boundaries. But the same interconnectedness provides the potential for solutions… required for a truly sustainable planet.

3. The defining challenge of our age is to safeguard Earth’s natural processes to ensure the well-being of civilization while eradicating poverty, reducing conflict over resources, and supporting human and ecosystem health.

“Saving civilization” can now be presented as practical the task of ending poverty and the conceptual work of thinking human and non-human systems as being so intertwined as to form one co-dependent network.

You can’t vote for this. You can’t expect the United Nations to enact it. You have to perform this set of changes and it begins very simply by refusing the global and imagining the Earth-system.