Whoever called Paris the city of light definitely wasn’t here on a wet Friday in December like today. You felt you were barely able to wake up. In the subterranean depths of the National Library, I time travelled to 1826 when France imposed an indemnity on Haiti for having declared itself independent. And from those old papers you could begin to sense how the free republic tweaked the nose of the old slavers and monarchists. You could also perceive how the modern debt system was from its beginnings a racialized tool of domination.

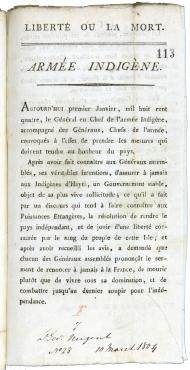

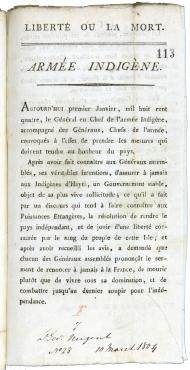

Haiti became free in 1804. There’s a few documents available that record the moment, like this text of the declaration of independence:

France did not recognize the new Republic and continued to hope that it might regain its old colony. By 1826, it was clear that this would never happen. Haitians had been free for a generation and what one French colonist called “the magic of slavery” no longer worked.

In return for accepting Haiti’s independence, France demanded an indemnity of 150 million livres, the old monarchist money. However, the true believers in colonial slavery were incensed. They valued their property in the former Saint-Domingue, including human property, at no less than four billion livres so this sum seemed derisory. A pamphlet and newspaper war began, sounding for all the world like Fox News, declaring that a war could easily be won in Haiti, slavery restored and the plantations reopened.

There are dozens of such documents in the National Library. They tell another story as well, one of the post-revolutionary debts of the old slavers, unable to get their hands on the indemnity because their creditors claimed it first or because bailiffs intervened.

Against that, there’s so little from Haiti but what remains is eloquent in its own way. Haiti passed a law in February 1826 accepting the indemnity as a national debt. There are two clauses to the law, which I was able to read today. Above was Haiti’s new coat of arms, which displayed powerful cannon suggesting that the country would defend its motto “Liberty or Death,” and replaced the fetishized cash crops, like sugar and coffee, with a splendid palm tree.

The law declared:

Article One

The indemnity of 150 million pounds consented to France in exchange for the full and entire recognition of the independence of Haiti, is recognized as national debt

Art II

The President of Haiti will take measures which his wisdom will suggest to him to liberate the nation from this debt.

So although the French portrayed the indemnity as compensation for the wrongful abolition of slavery, the Haitians presented it as a contractual exchange for the full and entire recognition of their independence.

And where the French law required an extensive 27 member commission to decide what to do with the indemnity, Haiti devoted one line to the not very important question of repayment. In the first year, they borrowed the money from France to repay to France. For the next two years nothing was repaid. French royalists worried out loud about the possibility that they might refuse to pay it.

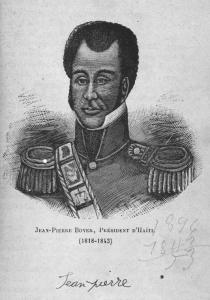

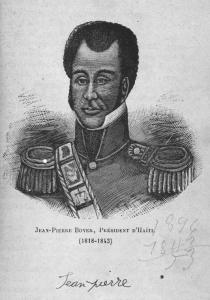

Working on that fear, President Boyer (below) had the indemnity reduced to 90 million.

But it was not all détournement and bluff. To repay the debt, Boyer had to establish a national bank of Haiti in 1826 and he compelled the subalterns to do forced labor to raise money.

But the implied leisure of Haiti’s emblem, the palm tree, was not lost on the colonists. The racist diatribes in 1826 against the formerly enslaved, accusing them of living in “indolence,” doing nothing but dance the bamboula, sleep in the sun, and eat tropical fruit prefigures both Carlyle’s widely-cited discourse against the emancipated of 1846–and of course the much desired “holiday in paradise” now sold to Northerners. What an irony: the tropical island depends for its hard currency on the former slave owners’ fantasy of the life of liberated slaves.

At Bowdoin College that same year of 1826, the second African-American to graduate from college gave the commencement address about Haiti. John B. Russwurm did not mention the debt. He was jubilant:

Can we conceive of anything which can cheer the desponding spirit, can reanimate and stimulate it to put everything to the hazard? Liberty can do this. Such were its effects upon the Haitians—men who in slavery showed neither spirit nor genius: but when Liberty, when once Freedom struck their astonished ears, they became new creatures, stepped forth as men, and showed to the world, that though slavery may benumb, it cannot entirely destroy our faculties. Such men were Toussaint L’Ouverture, Desalines and Christophe!

Such jubilant theory was exactly what the former colonists feared. They thought it meant the end of slavery and the Caribbean colonies and it did. Boyer thought he could turn the debt to his advantage and not overly burden his new nation in so doing. If he did not succeed in doing so, it was largely because the new imperialist era of the nineteenth century saw exactly what a threat Haiti had become.

Like this:

Like Loading...