“All hitherto existing visuality becomes aesthetic by being misogynist.”

This is the necessary update to my earlier claim that “the right to look ….is very much a feminist project.” Visuality is “masculine” or heroic because it is misogynist. It is that misogyny that enables its claim to legitimacy, that is, to make and embody law. The permanent and constituent crisis that visuality visualizes is that which claims to require patriarchy as its solution, a rear-view mirror engagement with the present. Case in point: Blade Runner 2049, the sequel to the classic Blade Runner (1982), on which every visual culture scholar has opined.

*

Before beginning this rewrite, let’s take a moment to say that I’m aware that this is not just any modulation of an analysis. It’s an admission of past failing that has been made glaring by present conditions. It’s up to you, the reader, to decide what to make of that. This is me beginning to try to do better by working it through.

In The Right to Look, the patriarchal authority to visualize is set against collective, democratic forms of countervisuality, yes. But I’m a little bit surprised looking back at it now to see that the feminist/gender/sexuality analysis is not well worked out. Why? I’m male identified, so that probably doesn’t help. There was a foregrounding of a masculine seriousness about war in the period I was writing (2003-10). I think, too, that I wrongly assumed the gender dimension of the ridiculous hyper-masculinity of the Heroic tradition to be both well established in visual culture analysis and so obviously reactionary that it did not need as much focus. And I was wildly wrong. Let’s start again.

*

misogynist visuality

“Visuality” is the specific technology of coloniality formed on the plantation by the overseer, generalized as a technology of colonial war, and later named in English by Thomas Carlyle (1840). All such misogynist visuality is the property of the Great Man or the Hero. To understand what this means, it is only necessary to know that present-day alt-right considers Trump to be such a Hero.

Colonial visuality operates in complexes, which classify (free from slave, for example) and then separates the classified orders. That order holds because it produces an aesthetic, that which Fanon called the “aesthetic of respect for the established [patriarchal] order.” This aesthetic is always nostalgic, always bound to what Carlyle called “Tradition,” always haunted by the fear of its imminent disappearance. Which is to say, it is always violent.

In the era of neo-colonial war in Iraq and Afghanistan, enabled by the drone, there was a return to overt ideology of “commander’s visualization,” to quote the US Army’s Counterinsurgency Manual. It also seemed as if that visualizing was not hegemonic. The “aesthetic” of permanent war (in movies like The Hurt Locker) felt unfinished and thereby contestable because there was no way to make it feel necessary and right.

That analysis underestimated the necessity of unfinish to the neo-imperial masculine aesthetic, the need it has to feel threatened and on the verge of being overwhelmed, to sustain and reproduce itself. “Chaos” is visuality’s always feminized other in Carlyle and in all subsequent claims to Heroism. The opposition to Heroism was, according to Carlyle, “the female Insurrectionary force,” always already racialized as “black.” Carlyle did not even bother to consider the possibility of a female Hero, which would (in his view) produce monstrous forms like Amazons and Maenads. “Female force” is Heroism’s internal challenge to be overcome, as a constitutive, embodied part of itself. This ideology is phantasmatic, even ridiculous, to be sure, but it has had very real effects.

Indeed, coloniality has now created a new form of heroic masculinity for the aftermath of the conquest of (M)other nature. Surviving in the midst of climate disaster is the new heroism visualized in Blade Runner 2049, in ways that bear little resemblance to lived experience. Today’s self-proclaimed Heroes embrace the earth system crisis as their chance to wage permanent misogynist war. Real men eat GMO, use pesticide, burn coal and master the resultant chaos because mastering (female) chaos is what (male) Heroes do. What follows is the spectacle of Trump minions advocating for coal at the climate conference, while only 8% of college-educated Republicans “believe” in climate change, as if it is a branch of theology. In this view, faith rests in the Hero, who welcomes climate chaos as a test of his strength.

2049 is now

Misogynist coloniality has created a nostalgic aesthetic, such as that deployed in the self-consciously “epic,” which is to say, “heroic” film Blade Runner 2049. It failed at the box office but so did Trump. For my generation of visual culture studies, the first Blade Runner was canonical, taught over and again. So its return was nostalgic for me too. Like Bertolt Brecht siding with the cowboys during Westerns–as he admitted he did–I can’t deny enjoying watching it, both for its intense cinematic experience of sound and image and for the postmodern Proustian resonance of rediscovering past media time.

But this film not only visualizes the white supremacist masculinity that is making the world toxic, it takes active pleasure in the toxicity of the world. It is now the visible analogy of the hidden-in-plain-sight violent, abusive, misogynist Hollywood system evoked by the name “Weinstein.” Everywhere you look in this extended exploration of white masculinity there are available, conventionally attractive, young, white female bodies, floating on the side of buildings; or activated as software when the Man returns home to his miserable apartment; or standing on the street waiting for sex work. In this future, a (male) wish fulfillment if there ever was one, no one is trans or queer, and hardly anyone isn’t white.

In Blade Runner 2049, the new white male hero, known only as K, is literally a machine. K (Ryan Gosling) embodies the Heroic interface of the corporation and the police, which Gramsci called Caesarism. K marches through the orange desert in post-apocalyptic Las Vegas in search of the lost original Blade Runner, Deckard (Harrison Ford). It’s radioactive but he doesn’t care because he’s a machine. If such orange effects usually result from desert winds, recently seen in the U.K., the hyper-smog today enveloping Delhi and Lahore is a suffocating grey that locals are actively comparing to Blade Runner. Without the “conquest of nature” anaesthetic to make it palatable. Unlike Blade Runner, helicopters can’t even fly in the dense, gritty air mass.

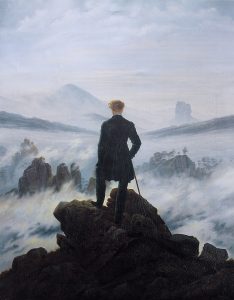

K’s wandering through radioactive Vegas is a digital upgrade of the industrial-era Romantic fantasy of the conquest of nature. In Caspar David Friedrich’s much-reproduced painting, the wanderer, known only through his bourgeois suit, is colonial master of all he surveys, like Keats’ Cortés, “silent on a peak in Darien.” What lies beneath him is said to be fog but most such precipitation in the period was coal-induced smog. It’s not so far from the Wanderer to K, except that the “human” (which is to say “white” masculine) gaze is now automated.

the machine gaze

How does the machine visualize? The first shot of BR 2049 fills the screen for a second: an all-seeing blue eye, with blond eyelashes. It is that of a replicant, an artificial person. Nowhere else in BR 2049 does this combination of blue-eyed blonde appear, so it is not the eye of a character. It is the ideal of machine vision, the machine as Hero. In the next instant, blink and you miss it, we zoom into the eye, into swirls of blue, and emerge in a giant solar panel array, converting the tomb-like sky into power.

All puns are intended by director Denis Villeneuve: the replicant’s eye is replaced by the solar “eye,” where neither is an “I.” Power is all, electric and social. If “we,” the spectators, are, as it were, in the eye of the machine, in their mind, then where are we? And who are “we,” when people are not always human?

The primary work of visualizing is classification, creating here an imagined distinction between the “human” and the machine, or replicant. Any such classification is a reenactment of the colonial hierarchy of the human, in which most people do not achieve the fully human status that is reserved for “whiteness.”

In Blade Runner 2049, all the major characters are machines. The only human that plays a role is the police officer Lt. Joshi (Robin Wright), desperate to keep “order,” meaning the separation between human and machine. It’s already too late. She’s killed by a replicant. The fully human “humans” are elsewhere in the place the film calls “off-world,” the new interstellar colony.

The replicant Luv (Sylvia Hoeks), who kills Joshi, achieves perfect machine visualization, sublimely reflected in her sunglasses that act as her remote screen vision. A machine-Medusa, Luv directs a lethal missile attack to protect K in his hunt for the natural-born replicant, a mechanical messiah. In the animation of her cyber-eye, Luv embodies all the current dreams of power, like that of the wide-angle drone apparatus named The Gorgon Stare. What Luv cannot do, the film suggests, is love. She is all war, the female counter-insurrectionary force machine, the necessary counterpart to the heroic drive of corporate leader Wallace (Jared Leto).

wish fulfillment

The sardonic displacement of “love” into Luv acknowledges the misogynist violence at the center of the story. Blade Runner 2049 centers around the pursuit of a child born to the replicants Rachael (Sean Young) and Deckard (Harrison Ford). In the first Blade Runner film (1982), Deckard falls for Rachael. When he tries to kiss her, she pulls away. He slams the door, pushes back into the blinds and makes her say “I want you.” Then she acts out the kiss. Did she love him? Or Luv him, as directed by her software? Deckard doesn’t care.

The YouTube post of Deckard’s assault on Rachael (labeled a “love scene’)

Deckard, we learn in BR 2049, was programmed to desire Rachael (meaning that he is himself a replicant, as everyone except Harrison Ford has worked out long ago). So the first film literally engenders the second with the birth of their child, which conveniently causes Rachael’s death. In BR 2049 we discover Deckard living out a bro-noir life of mourning and drinking in ruined Las Vegas hotels. Captured, he again causes the death of a newly re-replicated Rachael. Like Wallace’s casual murder of a newly-created replicant, this misogynist killing has no other function than to continue the wish fulfillment that violence is power.

For Deckard’s assault plays out the elemental pornographic fantasy that whatever a man wants, a woman does too. In the recent HBO series The Deuce, the sex worker turned porn film director Candy (Maggie Gyllenhaall) keeps reminding everyone that porn is “fantasy.” It’s as if she’s speaking out of character here in this sadly misogynist and racist series–beautifully staged and shot, just like BR 2049–as the present-day actor addressing the audience.

In the minds of assaulting men, anything can be a justification. Women’s words play no significant role in this justifying narrative. Yale students chanted “no means yes, yes means anal” in 2010, so this is (by the hierarchy’s own standards) a rot that spreads from the head. Maybe now Sean Young’s claims to have been abused by a studio head and Warren Beatty might be finally believed.

fetishism

In BR 2049, K doesn’t bother with complicated replicant Luv. He has an A.I. called Joi (Ana de Armas) instead, a software construct designed to meet his every need. Joi makes home dinners for him and then changes into vampy outfits, the digitized remake of the 1950s every MAGA man needs. The fetish she offers K is the siren call of whiteness: “You’re special.”

Joi “believes” this–or, more exactly, has been programmed to say it–so that K continues to do his work. In just the same way, the “wages of whiteness” like racist statues, the national anthem, and not being shot by police compensate for the not so perfect lived experience of actually being “white.”

Only K finds out that, despite his fantasy, he isn’t special, he’s not a naturally-born replicant, but just another shop-bought off-the-shelf model. Rather than give up his fetishism, he transposes it into the “noble death.” The rebel replicant leader suggests to him that such a death is the most human thing he can do, like Sydney Carton in Tale of Two Cities–whose 1935 movie ending was oddly watched in The Deuce as a form of sex work. K dies happily at the end, the first time he has smiled during the entire film.

But why would a machine that can see what humans have done to the world want to be human? There’s no reason that makes “sense” within the narrative, it’s just the old colonial fantasy that what “they” want above all is to be like “us.” And it’s the job of the Hero to stop them. Within the film narrative that doesn’t quite make sense but the real Hero is, in the cinematic fantasy, the male spectator, now aspiring to be a machine, a metaphor that also saturates sports fantasy.

condensation

K does achieve one notable visual first. Freud imagined Western male (hetero)sexuality to revolve around the (m)other/”whore” classification. These roles must then be separated to feel right and, goodness knows, a whole lot of “aesthetics” has followed from that separation. In a world where, according to the New Yorker of all places, incest is the top-rated theme in porn, such distinction seems more than a little quaint.

In BR 2049, K manages to have it both ways by inserting his eroticized (m)other Joi into the body of a replicant sex worker Mariette (Mackenzie Davis). The resulting not quite perfectly overlapping three-way was a tour-de-force of animation and white male peculiarity. What does the white (machine) man want? To fuck (with) his own software. Apparently.

white supremacy

What does machine visuality want? To sustain the separation between the human and the enslaved. In the first Blade Runner, the replicants are to be pitied as they are hunted down. Now the replicant capitalist Wallace demands the production of an enslaved machine labor force, creating a new hierarchy between the human machine and the enslaved machine.

The enslaved machine will be known to be enslaved in the same way that the United States knew its enslaved to be so: because they were their mother’s child. An enslaved person could be of many phenotypes and genealogies. But there was no gainsaying partus sequitur ventrem, literally “the offspring follows the womb.” Control of the womb is, as United States politics amply demonstrates, central to all coloniality. As Saidiya Hartman puts it, “the master dreams of future increase.” Androids may dream of electric sheep but the ones in charge dream of primitive accumulation.

In the imaginary of Blade Runner 2049, the ever-more perfect replicant can defeat the test as to whether it feels. But it cannot refute being its mother’s child, although that “kinship loses meaning,” as Hortense Spillers argues in the context of slavery, when “one is neither female or male.” Enslaved or machine, the meaningless of the non-human condition continues. The patriarchy wins on both sides of the film: the replicant natural-born child lives (win for Wallace’s slave patriarchy). Deckard lives, and like a latter day father of the Horatii, gets to claim the same woman as “his” child, free of both her mother and K, her potential love interest (win for replicant patriarchy).

the end of patriarchy. or the end of the world?

It turns out that it is not the end of capitalism that is impossible to imagine over that of the end of the world. It is that of patriarchy. Worse, for patriarchy to continue, it now imagines that its conquest of nature must continue, whether in the machine body, the transformed planet, or the racialized hierarchies of the human and the enslaved.