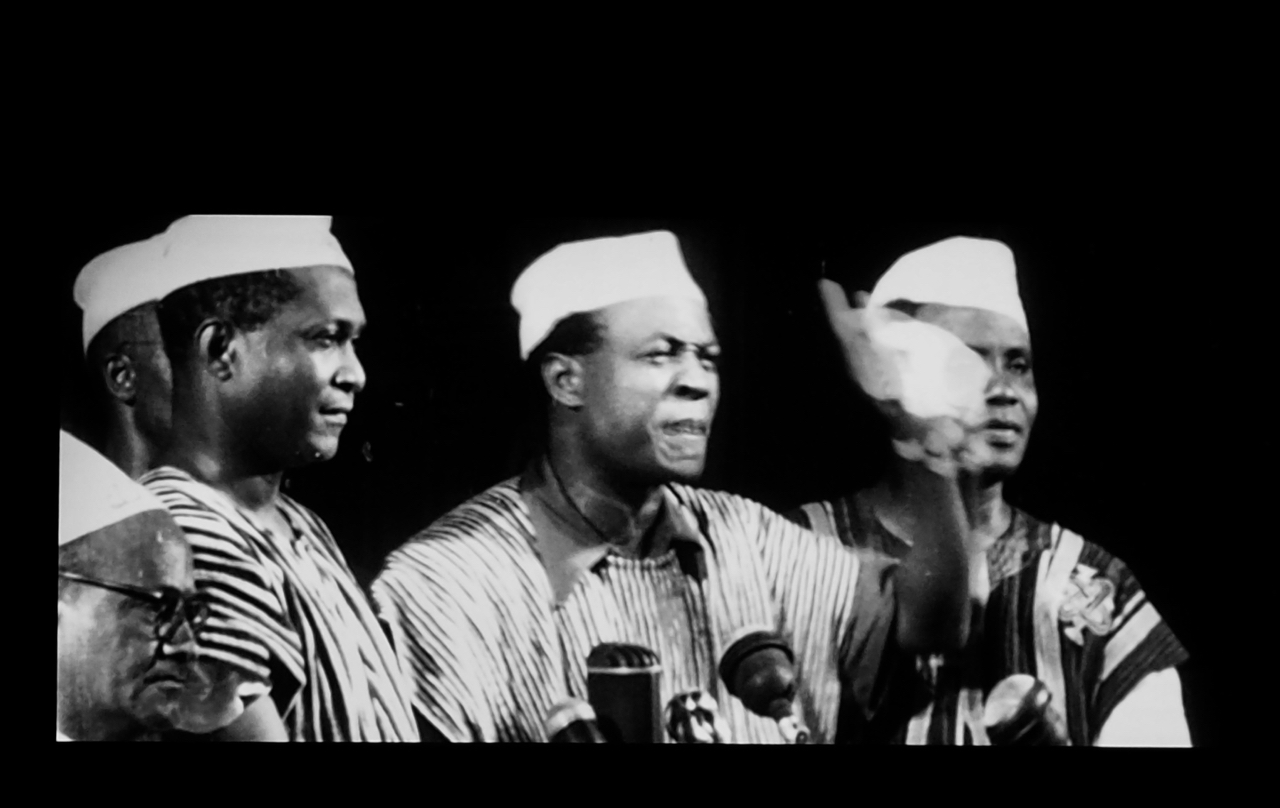

In transfigured night, hear the poet Milton sing “Hail, horrors, hail.” In this disjuncture, in the break and in the wake, the voice of Kwame Nkrumah comes: “We face neither East nor West, we face forward.” We, the would-be decolonized, was his formula in that betrayed beginning of Bandung, whose spirit continues to inspire. His phrase was as resonant for feminists in Iran as African American activists. To face forward is a positioning against racial capitalism, a setting of direction toward the dismantling of its infrastructures. Toward imagining decoloniality.

This place will document my efforts to face forward in order to engage with race as infrastructure, looking at monuments, museums and other display as constitutive of urban form under racial capital. By the same token, the segregated and unequal distribution of services and infrastructure within cities also requires what Shane Brennan has called “visionary infrastructure,” on the model of Grace Lee Bogg’s visionary organizing.

And Nkrumah’s voice comes again in Transfigured Night, reminding his listeners that they are free. But they’re not and he knows it and so do they. He’s asking them to remember the future. That time when there will have been what he called the “total liberation of Africa,” when the infrastructures of racial capitalism have been erased.

Forward is, then, at once a direction towards possession of the self, which is what freedom has meant in the Atlantic world; the formation of a communal sense of being decolonized; and a relation to time that is neither the progress touted by white liberalism nor the revanchism of reaction but a cosmology that relates human and non-human over the span of many lives. That’s not yet. Decoloniality is the future to be remembered.

Then Fanon’s words appear: “O my body, make me a person who asks questions.” What questions does the body ask? In Ghanaian filmmaker John Akomfrah’s two-screen installation Transfigured Night (2015) at the New Museum last summer, where I was thinking all this, it is asked: how did this narcoleptic state happen? How would the disalienation, Fanon’s term, of the body, yours or mine, happen?

Here are some of my questions, now. Has there not been a certain narcolepsy since 11/9, a certain sheltering in place, a certain discombobulation under the constant stream of tweets, executive orders and deregulation that has made it hard to know which way I have been facing? Against, yes. Forward, not always. Is it not now past question that no single moment, whether of voting or direct action, is likely to shift the global direction to authoritarian white nationalism? The city feels restive. Movement in the shadows. An awakening, or better, re-awakening is at hand.

On the screens now, monuments. Lincoln. Washington. Visited by the heads of decolonized states in Technicolor archive footage, the remembered brightness of past possibility. Transfigured into the blue-steeled glass of the corporate present. Figures still face forward but Washington’s “liberty” and Lincoln’s “emancipation” are no more present than Nkrumah’s “decolonization,” specters all. But specters return, they are the future, they remember it.

What, then, of the Indigenous whose land was taken for these monuments, whose loss is the infrastructure across the Americas? The territorial acknowledgement has become widespread, as it is in Australia, Canada and Aotearoa New Zealand. As those countries’ histories suggest, it is not enough. Land redistribution in South Africa was one of Trump’s racist panics in the past election. White nationalists cheered, globally. What, too, of those Cheyenne-Arapaho writer Tommy Orange calls “urban Indians,” seven out of ten of the Indigenous population?

Akomfrah ends his installation at what he calls “beginning”. His figure, an African elder, faces forward to the emptiness of gentrified Seattle. The material infrastructure of white supremacy. Race as infrastructure is a set of assemblages that articulate colonial race theory, history as colonial destiny, and the exploitation of labor, made “normal” by what Fanon understood as “the aesthetic of respect for the established order.” The museums. The monuments. The new housing developments with their token “public art” and “parks.” It needs to be articulated as an assemblage, together.

At the foot of the towers, from Luanda to London, Cape Town to Charlottesville, global cities are still networked by what Fanon saw to be “a compartmentalized, manichean, immobile world: the world of statues.” Stone colonialism looks down on people and claims dominance, hierarchy, history, via white supremacy, whether from its towers or from a pedestal. They look down. We look forward. The statues are a weakness, too obvious, too contemptuous. When they fall, it is just the beginning.

Their strategy is still to compartmentalize, to contextualize and to prevaricate. They say: Let’s think about adding a sign? Maybe another monument? A conference? Doesn’t this statue have “artistic merit”? Forward gets past the statues to the world they immobilize.

The opposite of stone colonialism is what the 19th century revolutionaries in England called “the mobility.” Counter to the world of statues, Fanon dreamed of running. Get Out wanted to escape the Sunken Place. It’s Fallism, but it’s more than falling, it’s movement. Forward movement.

[i] Kwame Nkrumah, “From now on we are no longer a colonial but free and independent people,” (March 6, 1957), quoted in John Akomfrah’s two-screen installation Transfigured Night (2015). Full text at https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/2017/March-6th/full-text-first-independence-speech-by-kwame-nkrumah.php

[ii]Fanon , Wretched of the Earth, 15,translation modified.