In the past week, the ubiquitous Confederate monuments have suddenly become visible (to non-Confederate sympathizing white people) as monuments to genocide and white supremacy. It’s important to continue to show their systemic role in making and sustaining white supremacy. In particular, the monuments form a network that connects seeing, unseeing, lynching and gender in ways that I for one had not previously fully understood.

seeing and unseeing

The sheer numbers are astonishing. Over 13,000 Civil War memorials. 700 Confederate monuments on public land, including Arlington National Cemetery and the US Capitol. Statues of Robert E. Lee at universities like City College, New York, and Duke. That’s a system, an infrastructure of white supremacy that has been hiding in plain sight across the US. Now begins the process of learning to unsee the unseeing of them.

But the statues were always watching. In the Vice documentary on Charlottesville, one African American woman comments that the statue of Robert E. Lee seemed to watch her wherever she went. The monuments are racialized CCTV, placing those designated “not white” on notice that white supremacy is watching. They materialize the mystical power of “oversight,” once embodied in the plantation overseer, and now part of segregated public space.

material mourning

The monuments convey that power not by artistic skill or visual creativity but by sheer mass. These were mass-produced objects, made by companies like McNeel Marble. They had massive height and weight. When Louisville, Kentucky, decided to take down its monument, nearby Brandenburg put it back up. It’s 70 feet tall, 100 tons of granite and now re-mounted on 80 tons of concrete. In and of itself, this materiality dominates. By its simple presence it makes a statement as to who “counts” in America, who is grievable, and who is not.

Via the monument, the materialized power of (over)sight forms specific sites within the matrix of white supremacy. Take the thirty-four foot high monument in Pensacola, Florida, paid for by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in 1891. At the time, the city was majority African American. It had been been captured from Native Americans and free Africans by Andrew Jackson in 1817.

The monument dominated the local landscape when first installed (as in the 1907 postcard above). A year later, Leander Shaw, an African American man accused of assaulting a white woman, was lynched nearby. Over 2000 bullets riddled his corpse, after he was hanged from an electric pole (yes, there’s a picture; no, I’m not posting it). When the local high school was “integrated” in 1975, a race riot ensued and attracted a major KKK rally to the monument.

In the past week, the mayor has called for it to come down, only to meet determined opposition from the local Republican congressman and a 5000-signature petition. Which in turn generated 2300 signatures supporting removal (possibly to a nearby cemetery). Now a weekend rally has been called in support of the monument.

Here, then, is a metonymy of what these monuments stand for: the conquest of Indigenous populations; the subjugation of African Americans; white supremacy and the myth of white womanhood; the former Republican “Southern strategy” of electoral domination; and now the metonymic conflict over the monument.

the site and sight of lynching

In other cases, as in Brooksville, Florida, and Hot Springs, Arkansas , lynchings actually took place at the site of the Confederate monument. Take the case of Caddo Parish, Louisiana. It was the second largest site of lynchings nationwide. In 1903, the UDC put up a Confederate monument. Six months later, three people were lynched at the site on November 30, 1903, from the tree visible in the photograph below.

A typical “Silent Sentinel” monument, the Caddo Parish example is thirty feet tall, dominating its locale. The woman in front represents Clio, the muse of history and the inscription reads “Lest We Forget.” The site could better serve as a memorial to Phil Davis, Walter Carter, and Clint Thomas, the lynched men.

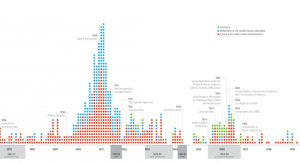

In general, it’s noticeable that there is a rough correlation in the incidence of lynchings and the numbers of Confederate monuments.

Both “peak” in the decade after 1890, as Jim Crow became fully established in the South, with an upturn again in the 1920s with the revival of the KKK. I do not think that the monuments “caused” lynchings or vice-versa. Rather, both were interactive instruments of violence in instituting and sustaining white supremacy.

This interaction can be called the “sight of lynching.” As in the case of Leander Shaw, many lynchings resulted from the testimony of white women, often without other evidence. In the common instance of “reckless eyeballing,” (which I’ve written about here) the accusation was that an African American person had looked at a white woman with sexual intent, as in the case of Emmett Till.

There is, then, a relay to be explored between the oversight materialized in the Confederate monument; and lynchings based on embodied perceptions of being looked at. The white gaze was at once surrogated through the monument and expressed as the power to remain unseen (in the case of the monument) and unseeable (in that of white women).

What was both seen and unseen was the spectacular and appalling violence of lynching. In 2018, the Equal Justice Initiative will open the Memorial to Peace and Justice, the first prominent memorial to the 4000 victims of lynching. Yet as many exhibitions and publications have shown since the groundbreaking Without Sanctuary exhibit (2001) [caution: very distressing images], lynching itself was intensely mediated. There were postcards, photographs, newspaper stories and public events. Nonetheless, only one white man was convicted of lynching in its eighty-year heyday.

white mythology

Further, the Confederate monuments were, as has been widely noted, often paid for by the UDC or other Confederate women’s organizations. Fundraising for the Pensacola monument was failing until the UDC became involved. Perhaps unexpectedly, white women’s activism made the network of monuments possible. Women are even active in today’s white supremacy movement, despite its visible misogyny.

In her 1952 memoir, UDC leader, Dolly Blount Lamar claimed that the monuments expressed:

in permanent physical form the historical truth and spiritual and political ideals that we would perpetuate.

This “truth” was very specific. When a historian at the University of Florida expressed the view in 1911 that

the North was relatively in the right, while the South was relatively in the wrong

members of the UDC drove him out of his job. When we hear the call to respect “history” on all sides, it is such falsified and white supremacist history that is at stake.

segregation forever

These monuments remain active today. One instance of the work they do for white supremacy is to act as “border” markers in segregated cities. It’s not just in the former Confederacy that this happens. The statue of the appalling J. Marion Sims, who performed medical experiments on enslaved African women without anesthetic, does this work in New York City today.

To the North of Sims is so-called “Spanish” Harlem, a diverse area of Black and brown people, dotted with housing projects and schools offering free meals to anyone under 18. South is Central Park and Museum Mile, where white people play whiffle ball and look at the monuments of white “civilization.”

anti-antiblackness

I have not been to the mountain top. I do not know what comes after white supremacy. I continue to be engaged in the work of anti-antiblackness which means negating the regime of white supremacy by making the monuments and the work that they do visible: and thereby removable.