Four years ago, there was a financial crisis. People put a huge effort into electoral politics around the theme of hope. Many of those hopes were imprecise, just a sense that things could only get better. A year ago, people took to the squares to renew their hopes by direct democracy. Again, the issues were imprecise but this time by design. The Presidential election this year was not about hope. Perhaps the difference now is that it is the nature of the crisis that is unclear. Is it about energy and climate? Debt? Democracy? The answer that frustrates people is probably the right one: all of the above. So what is the affect of this multi-dimensional crisis if it’s not hope? For Occupy, it’s love.

One of the most dividing terms in the Occupy movement has been “love.” Movement people like to talk about it as a key motivator and form of social engagement. Critics ranging from Zizek to Thomas Frank have looked down on the idea, and warned against the movement falling in love with itself. In other words, what we call love, they saw as narcissism, or masturbation. Trust two middle-aged white guys to tell everyone who they should fall in love with.

To be fair, their follow through was very different. Frank was comparing Occupy to the Tea Party and their “success” in having Ryan nominated as Vice-President. As a grouping resistant to representation, this kind of goal was never mentioned in Occupy. Zizek’s critique was that we could not imagine the future that we wanted. Perhaps that would have been an investment in hope, which predicts a better future. Love is a less certain emotion–it might be great, it might not, but your choice is to go with it because at some level you feel you must.

Psychoanalysis wants to tell you that not only do you not know what you want, what you think you want is a displacement of something else. There’s no doubt that the mechanisms of displacement and disruption (the slip of the tongue) are part of the present mental apparatus. How does this work politically? When the students of 1968 pushed Jacques Lacan on this question, he famously sneered back at them

What you aspire to as revolutionaries is a new Master. You will get one.

His meaning was the “revolution” would end up as a new form of reaction. Less noticed has been the exchange in which Lacan admitted to the students that the Oedipus complex on which such negations are based was itself a colonial imposition. It is that complex that disrupts the individual’s claim to know itself by a disruption from the Real. But this Real isn’t really real: it’s a colonial construction of a reality that was certainly experienced as such but, like all constructions, can fall down.

Decolonizing is, then, first a personal project of deconstructing and then reconstructing a mental apparatus that can be something other than the “individual” presumed by the patently collapsed neoliberal economic market. This reconfigured means of relating to others would be what we have struggled to call “love.” We’ve seen a great deal of it in the disaster zone this past week.

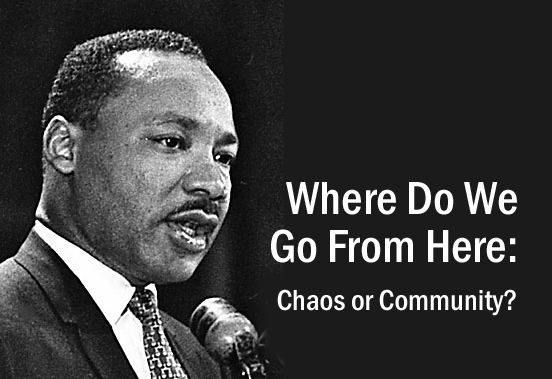

The debate is now over how this remaking of a sense of community can be made more permanent and how it can be scaled to a larger arena. The European-Mediterranean movement is ahead of us here. Their continent-wide organizing and community building is much more established and I’ll report back on this tomorrow. In this, there is hope. If a continent so radically divided by religions, languages, politics and history can forge a common movement, then hope is a way to do politics in the present, not some future to come.

And do we need it, the next storm is headed to NY and NJ with tens of thousands still without power, with coastlines totally vulnerable to storm surges, tunnels still flooded.