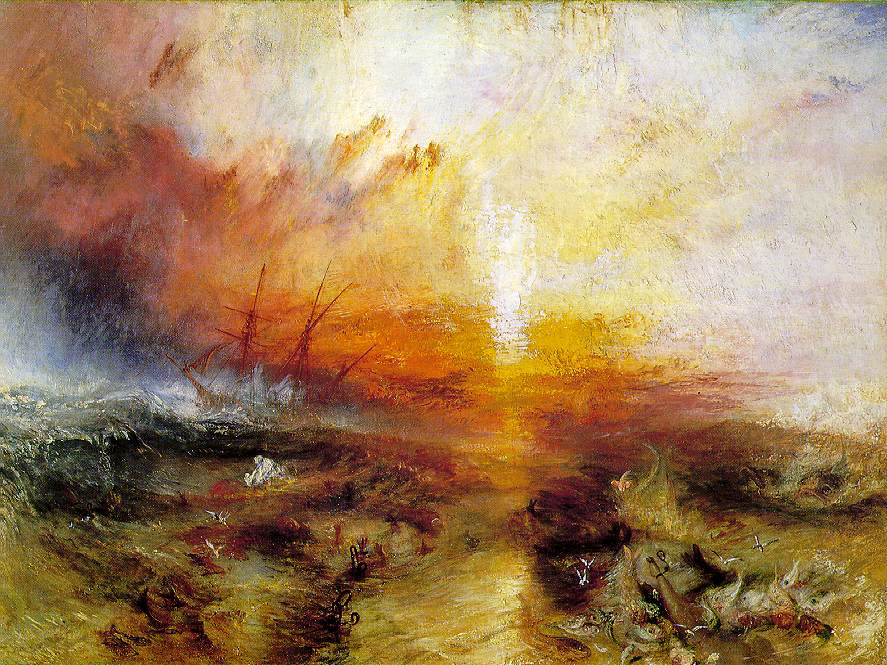

Last night, ironically enough, I should have been participating in a panel called Nightmare on Wall Street: the One Percent and the Ecological Crisis. Today with great fanfare, the wretched Stock Exchange reopened, powered by a polluting generator, even as all around the power was out and people with different mobilities were stuck in buildings. Goldman Sachs remained powered up throughout the storm, no doubt having its own generating system. Meanwhile, people in NYC were forced to take holidays to cover the days lost if on salary, or were simply unpaid if not.

Last night, ironically enough, I should have been participating in a panel called Nightmare on Wall Street: the One Percent and the Ecological Crisis. Today with great fanfare, the wretched Stock Exchange reopened, powered by a polluting generator, even as all around the power was out and people with different mobilities were stuck in buildings. Goldman Sachs remained powered up throughout the storm, no doubt having its own generating system. Meanwhile, people in NYC were forced to take holidays to cover the days lost if on salary, or were simply unpaid if not.

Downtown has been abandoned to fend for itself. The legions of wait staff, creative economy people, freelances and other precarious labor, who keep downtown what it is, are not working and so are not being paid. In high-rises below 34th Street, people with mobility issues are stuck. On the floor where I usually live–the 14th–there’s an elderly woman with a walker, a young woman in a wheelchair and a man with an electronic chair. Another man has heart issues and really should not be walking up 14 flights. And that’s just the people I know. Water is being restored to city housing by generators but that leaves tens of thousands without. The statistics about cell phone service are wildly different to the experience of trying to make a call. The social connections are being broken, not just the electrical circuits.

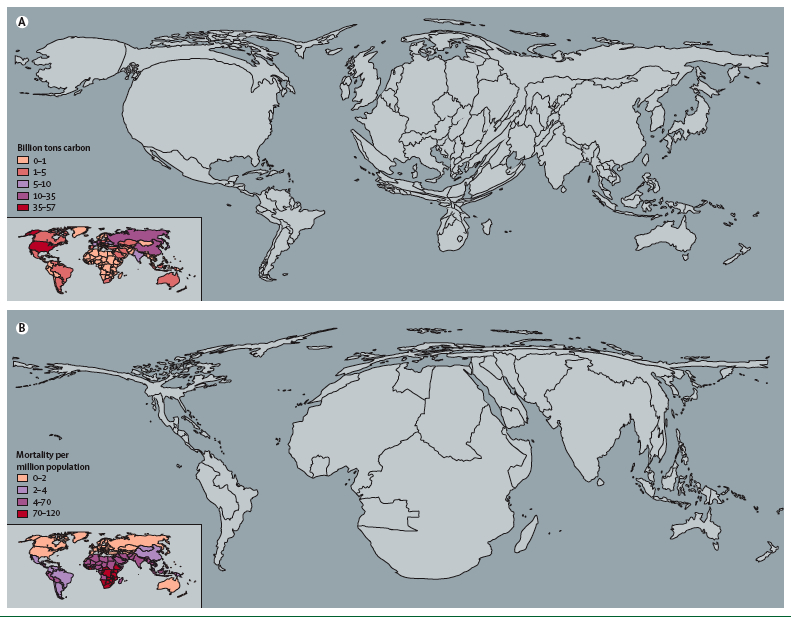

Further the climate disaster is being followed by a disaster for the climate. Generators are running everywhere, people are driving who would normally use mass transit and so on. The “climate” is an abstraction and so is the “economy.” In modernist practice, there was a division of mental labor designed to elucidate what was “really” happening. Whatever the name for our current condition, this separation no longer helps. All our grievances are connected. The social hangs together by a series of such connections, which can be broken as easily as water entering a fusebox. Once down, such connections are much harder to restore.

In relation to this idea, Peter Rugh’s essay at Waging Nonviolence has a rousing meme that will motivate all of us trying to connect climate work to political activism:

we’ll need an environmental movement as radical as reality itself.

For those of us still struggling to come to terms with the material impact of Sandy–no power, no water, no phone–this is not yet the moment for long essays in response to the motivating force of Pete’s call. But I hear it.

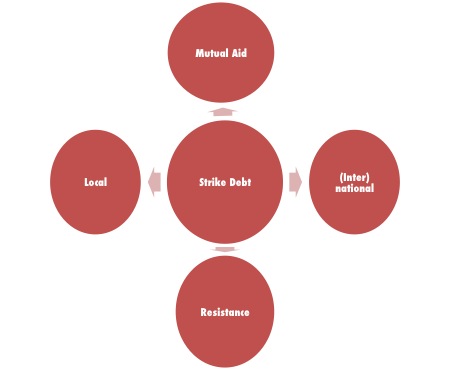

And it makes me think about the way that Strike Debt has been able to address the reality that so many of us experience–debt–and has thus made it possible to radicalize it. To follow the example in Pete’s essay, the Black Panthers supplied free breakfast for children that needed it and offered health care for those who could not afford it. If there is to be more than a green-washing moment after Sandy, we’ll need to be able to do those two things: first, find a way to identify the impact that biosphere destruction is having in people’s everyday lives in order to even think about alternatives; and second, offer mutual aid and sustainable alternatives, just as so many are doing in the streets of New York right now.

It’s about finding the connections and then finding the way to make them visible and sayable. So, as I have been saying, a debt strike is also a climate strike. Debt abolition is climate change mitigation. Because the way that debt is “repaid” is by more growth, which inevitably means more carbon emissions. Abolish debt, abolish those emissions. The Jubilee is not just a liberation of human misery but a breathing space for the biosphere.

But just as debt abolition can only be the first step to the end of the system that creates debt, so must a pause in emissions lead to systems of social connection that don’t rely on the oil-coal-steel-auto-defense nexus of the military-industrial complex. That’s the abstraction. The reality is what’s happening in New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, West Virginia and everywhere touched by the disaster.

Today we learned that it would have cost about $10 billion to install floodgates at the entrances to New York Harbor. Not by coincidence, that is also the estimate of what it will cost to restore mass transit. They “couldn’t afford” the first, so now we all have to pay the second via higher transport costs. And so on.

Take a small step. The People’s Bailout on November 15–recovery permitting–intends to raise money to abolish debt. $5 will abolish $100 of someone’s debt. You can be part of the awareness raising by donating your Twitter account once a day to retweet a Strike Debt tweet. No other changes to your account will follow, just once a day, your followers will see a Strike Debt tweet retweeted by you. Join the resistance.