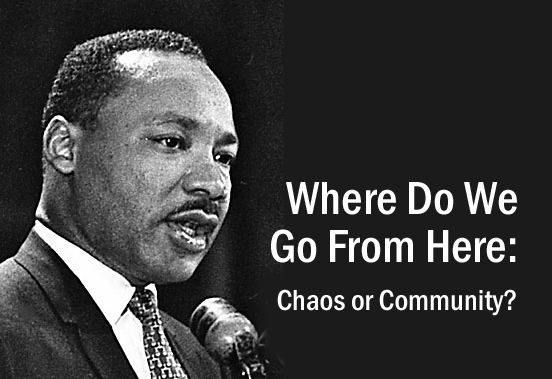

I led a workshop at the Free University of New York City on Strike Debt and one of the participants was an African American woman who had been active in the civil rights movement. She exhorted us to remember Dr King’s idea of “the beloved community” and to follow the lead of groups like the Student Non-Violent Co-Ordinating Committee. Then yesterday the activist and writer Rebecca Solnit proposed that Occupy was precisely a form of beloved community, one that came together in response to disaster.

In her book A Paradise Built in Hell, Solnit offered a stunning reversal of the fundamental neo-liberal worldview. As Mitt Romney so disastrously confirmed in his 47% video, neo-liberalism believes people to be fundamentally “brutish.” The term comes from the political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, whose distate for the “multitude” has been much noted of late. Hobbes argued that only a centralized, authoritarian state could mitigate the fundamental violence of the human animal.

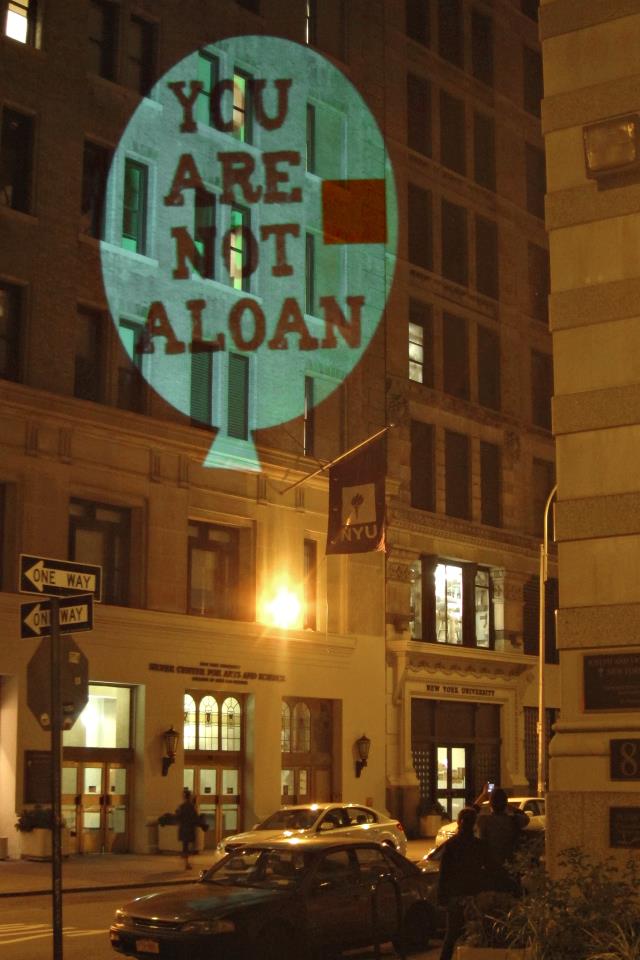

Solnit shows how this presumption structures official responses to disaster and catastrophe, such as the wildly inaccurate claims of mass looting, murder and rape in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Solnit describes how, not only are such charges wrong, but what actually transpires after disasters are remarkable instances of mutual aid. At her teach-in yesterday, she proposed that OWS was one such instance of this response. There had been a disaster, in this case, a financial one. People responded by providing shelter, food, clothing, medical care and other fundamentals, free of charge and in a collective fashion. It was clear to all that such provision was a direct challenge to the normative capitalist economy, leading to the evictions on the (spurious) grounds of “brutish” dirt and disease.

In her book, Solnit develops this contrast into a theoretical distinction that she borrows from the apparently unlikely source of William James. In his lectures on Pragmatism, James asked:

What difference would it practically make to anyone if this notion rather than that notion were true?

Solnit applies this to disaster and reformulates it:

What difference would it make if we were blasé about property and passionate about human life?

That’s a great way to pose Occupy’s challenge to neo-liberalism. Its radicalism was the palpable sight of all kinds of people placing the beloved community as a higher value than material goods, not in the name of a renunciation of the world, but of a radical change to it.

It might also suggest that the local and small-scale nature of Occupy is in fact an apposite response to the disaster of capitalism. As an Oxfam report on Cuban responses to disaster put it, there is a:

distinct possibility that life-line structures (concrete, practical measures to save lives) might ultimately depend more on the intangibles of relationship, training and education

than the wealth so beloved by neo-liberals.

So small-scale organizing centered on community, training and teach-ins is not a utopian alternative to capitalism but the best available response to its disaster. Lessons to be learned here by Strike Debt as it moves from being a campaign to a movement.