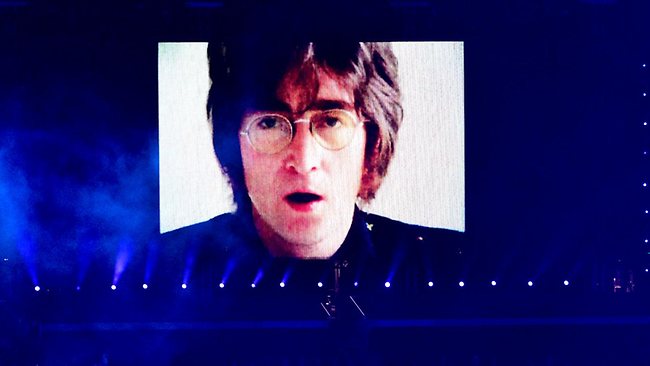

Very early this morning Australia time, I saw John Lennon singing “imagine no possessions” as part of the Olympic closing ceremony. Kim Gavin has used the often blander-than-bland Olympic ceremonial to restate a case for Britishness as a form of collective and international experience. It’s a revisualizing of the national imagination (hence “Imagine”) that was surprisingly effective, recapturing some of the energy of the Make Poverty History and Jubilee 2000 campaigns. What’s next? How about this: “imagine no borders.”

For this positive version of the national was then undermined during the course of the day by a dispiriting debate in the Australian media about immigration and asylum seekers. It seems that the 4500 asylum seekers a year who reached Australia last year has gone up to 7500 this year. Actually, they make their way to a piece of land that is “Australia,” not usually the mainland but a remote island, or get picked up by Australian navy vessels at sea. When I was last here in 2001, the country was convulsed with a debate following the decision of then-Prime Minister John Howard to turn asylum seekers away. A vessel named the SS Tampa was the flashpoint, with Howard falsely claiming that asylum seekers had thrown their children in the sea to compel a rescue by the Norwegian vessel.

Since then, Australian government has taken a series of repressive measures against immigration, forcing asylum seekers to be “processed” offshore for a period in locations like Nauru, an island threatened by sea-level rise, devastated by mining and desperate for revenue. Today the Labor government accepted a report proposing that asylum seekers again be processed on Nauru or Manus Island. The opposition are against this, not for humanitarian reasons, but because they want the boats to be turned back altogether. They all agree that having a family member in Australia should no longer be grounds for asylum. Only the Greens are willing to denounce the whole affair.

Here is one of those aspects of the nation-state that elude me. I don’t get why America can’t do anything about guns, why Britain is obsessed with the monarchy and so on. By this token, why is a continent-sized country with a population of only 18 million so exercised about this small number of migrants, people so desperate that they are willing to sail the Pacific in small, leaky boats? Is it so impossible to imagine living together?

The glib answer would talk about long histories of Australian racism, and perhaps there’s something to that, but it doesn’t fit in so well with the current effort to visualize Australia not as part of the Northern Anglophone sphere so much as a key hub in the Asia-Pacific region. On the street and in the media, it’s a notably more diverse self-image than it was a decade ago.

Perhaps it’s all just too hard to imagine–or better, to make coherent from a single point of view. I remember standing on a beach in Rarotonga, part of the Cook Islands. At that low level, there’s an optical illusion in which the sea appears to be higher than the land and it gave me a kind of vertigo. It wasn’t that you felt that the sea would in fact drown you, but that it was overwhelmingly obvious what a minute data point one person is in relation to a space the size of the Pacific Ocean. I’ve had that sensation quite frequently during Occupy, when the sheer bulk of capitalism appears dizzying. It’s as if you are at risk of disappearing into the vanishing point of the perspective created by the nation-state.

I was reminded of the experience by an article in the Sydney Morning Herald about Tuvalu (pronounced Two-VAH-loo). This tiny atoll nation is only two metres above sea level on average and the reporter Matt Seigel experienced the strange effect of seeing the sea as “above.” Tuvalu has strenuously campaigned to make the threat to its existence from sea-level rise part of the international agenda, with limited results. Some islands have already been evacuated and the government wants to secure a destination for its population of 10,500. No one seems willing to admit them, although there seems to be an assumption that in the end New Zealand will do so.

Tuvalu is not a paradise (above, the garbage dump on Funafuti). There’s issues with water, garbage, fish supplies and so on. One thing is clear from interviews with local people. None of them want to leave. Instead of doing something to make it more likely that they can stay, government policies have been directed towards preventing them from leaving a flooded land.

But why is it so hard to imagine no borders? Money has no borders, it moves freely wherever people choose to send it. Yet the longer “globalization” has gone on, the harder it has become for people to go where they want. Border checks are longer, more capricious, and more overtly hostile than ever. There is, it seems, a certain comfort to be had from the smack of authoritarianism. You are not in charge, but at least someone appears to be. Can we imagine the vertigo of embracing the vanishing point, in which there are no borders, only people, and the not terribly complicated things that they want and need?