I’ve been nervous all day, as if I was organizing a conference or a public event. It’s silly really, but I can’t shake the feeling. It’s the same question: will people show up? Other than the Occupy crowd, that is. It’s been a day of running into people who are getting their last minute things done, looking forward, feeling excited and edgy.

I’ve been nervous all day, as if I was organizing a conference or a public event. It’s silly really, but I can’t shake the feeling. It’s the same question: will people show up? Other than the Occupy crowd, that is. It’s been a day of running into people who are getting their last minute things done, looking forward, feeling excited and edgy.

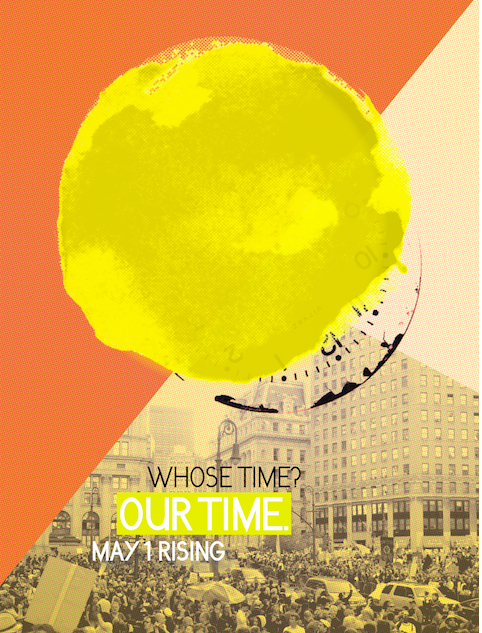

It feels like much is riding on this one day, perhaps inevitably, given that months of organizing have been directed here. The cops have apparently also been practicing on Rikers Island with fake protestors. It’s frustrating to learn that the weather is forecast to be wet all morning for the first time in ages–the gods are not surprisingly in the one per cent it appears.

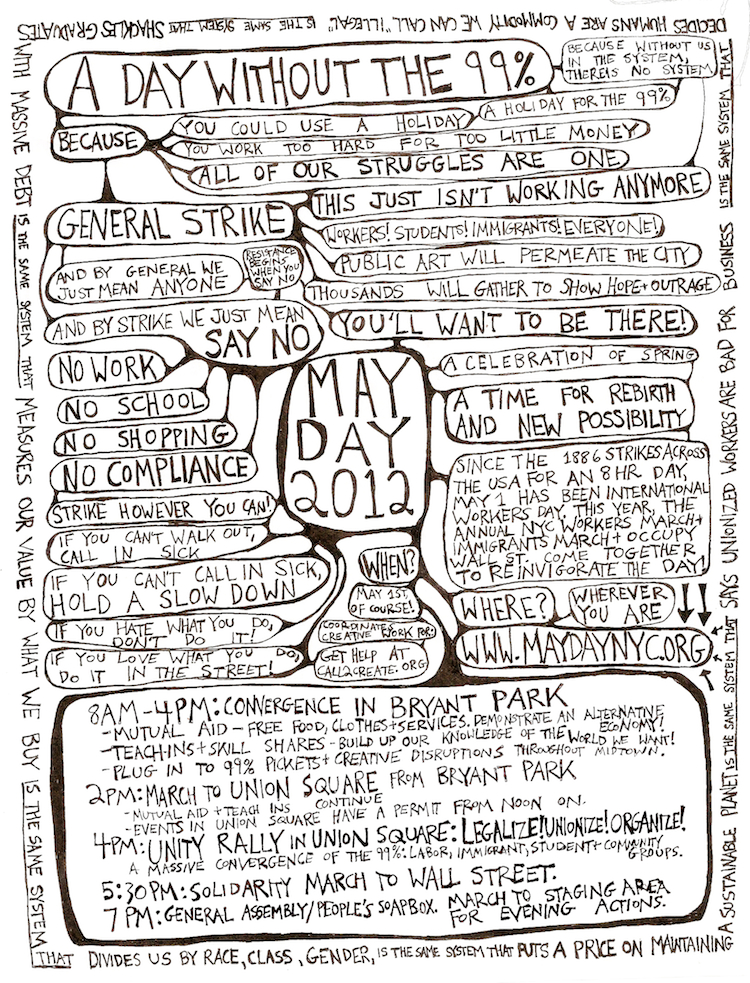

So here’s my schedule for tomorrow.

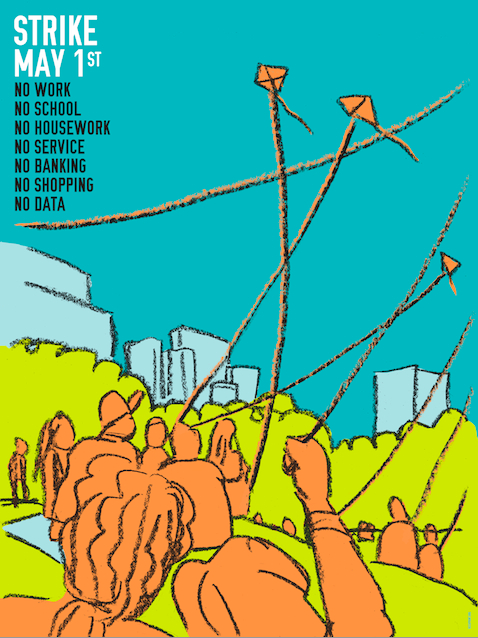

8.30 am: 99 Pickets. There are pickets being established of 99 corporations and other institutions of the one percent. While we’re on strike, they need to see that there’s opposition. Some of these have been announced but most have not, so it’ll be interesting to see how this tactic plays out.

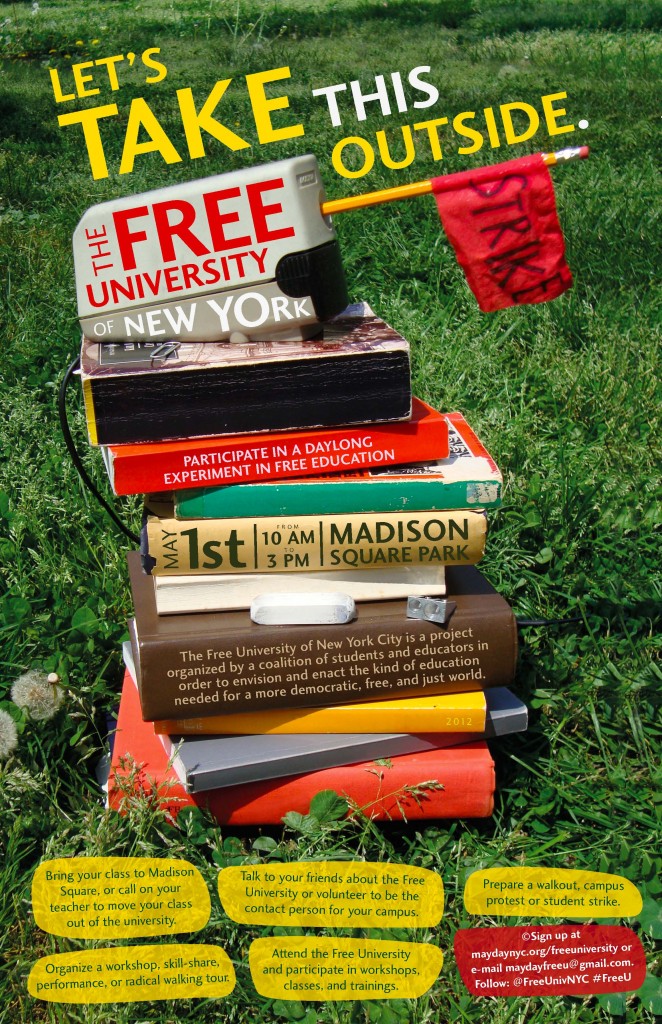

10am to 3pm. Free University!

There will be over forty teach-ins and appearances including David Graeber, David Harvey and Frances Fox Piven. You can learn about drama, yoga, Take Back the Land, anthropology, urban space and more. Enjoy Radical Recess. I’m helping out and about 2pm I’m part of the Occupy Student Debt Campaign reading performance of Can’t Pay! Won’t Pay! We have real performance people in the other roles, so I’m hoping not to make a fool of myself–luckily the play is a farce so maybe it won’t be noticed!

Around this point, the rain is supposed to stop!

5.30 March downtown with the Occupy contingent

7.30pm on: Occupy after-party TBA

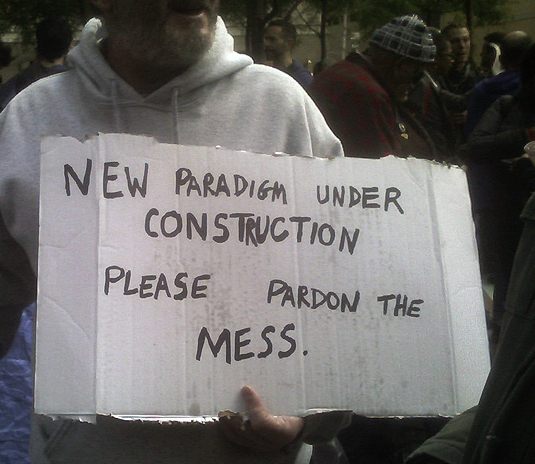

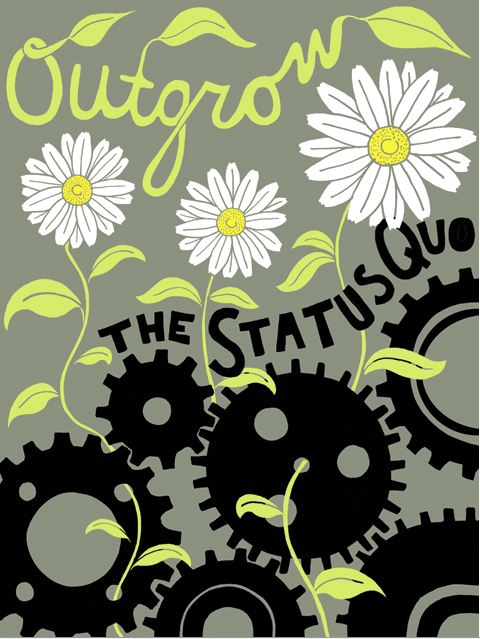

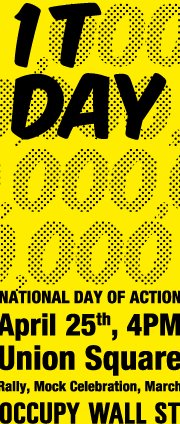

There are great actions going on all over the city. There’s public art everywhere and guerrilla libraries. One thousand guitar players will march in the Guitarmy from Bryant Square to Union Square. High school students are planning to walk out in solidarity in the Bronx.

From time to time, there have been disagreements about tactics or even whether having a May Day event was a good idea. Now I think we can all just agree to hope that what’s happening across the country tomorrow goes really well, that no one gets hurt and that no one who does not choose civil disobedience gets arrested.

One of the later suggestions for tomorrow is: No Data! So there will be no post on Occupy 2012 tomorrow. Good luck everyone and have a great May Day!

See you back here May 2